Bowhunter – Chapter 3

Chapter 3 of Bowhunter

Chapter 3 of Bowhunter

The Acromion Divot A Movement-Based Approach to the Bow Shoulder A Perspective on Movement I want to start by saying that I am not an archery coach, and I am under no delusion that I am. What I do have,…

Very rarely in our lives do we meet someone who, through their very existence, inspires in us the desire to become better. No one is born with that gift. It demands sacrifice, and it often grows out of difficult—sometimes dramatic—events.…

Which servant flies truer than any oath, drinks the heat of a living wrist, obeys a boy’s tremor and a god’s vanity, and yet carries a sovereignty that begins at release and ends only where the point decides? A glove…

In archery, the follow-through is arguably more critical than in golf or tennis, because the “engine” of the shot is the tension in your own body. While the arrow leaves the bow quickly, any collapse or movement at the moment…

Author: Dr. Antti Rintanen The paradox of archery performance lies in its demands: absolute physical stillness paired with intense mental alertness. Research demonstrates that elite archers who maintain lower heart rates during competition tend to score higher than those with…

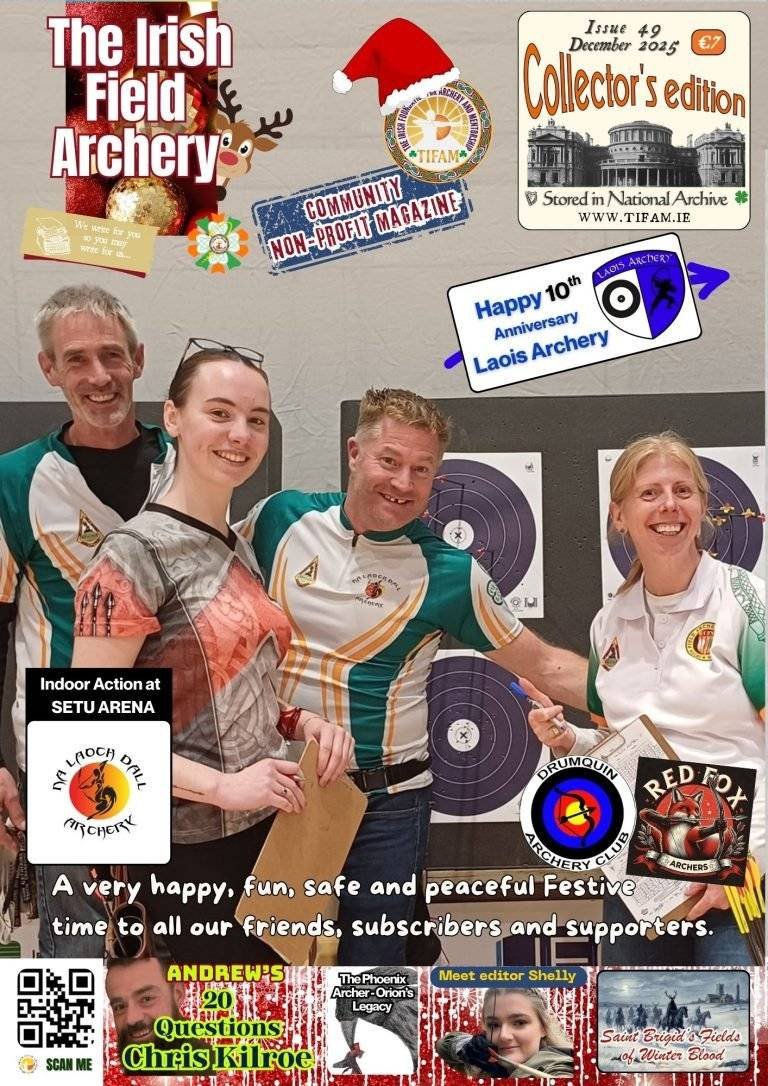

TIFAM Issue 49 (Dec 2025) mixes club news, interviews, competition coverage, photo specials, and seasonal fiction: it opens with a Christmas message from the team and features editor Shelly Mooney (historian/artist/writer and longbow archer with Dunbrody Archers, Wexford) plus her…

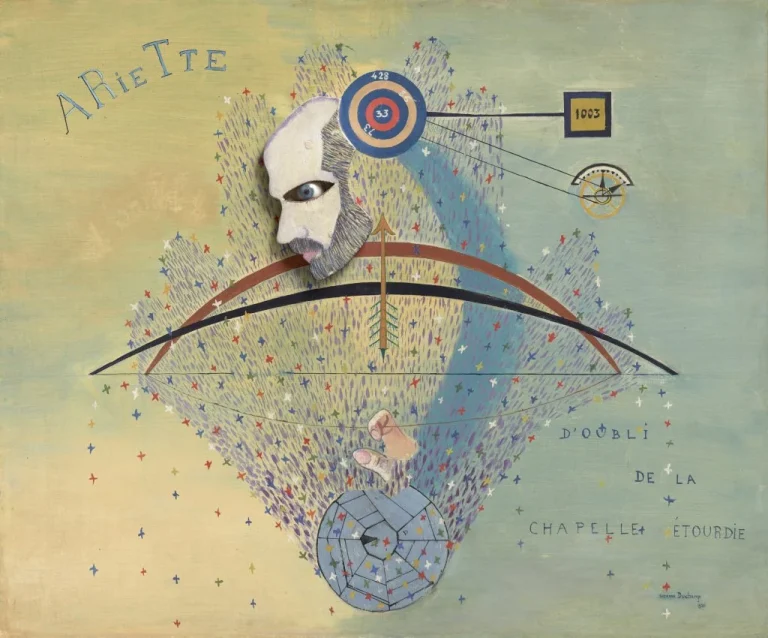

A pale field, washed like chapel plaster after incense has settled, holds its own weather, and in that weather a severed head—half mask, half reliquary—floats as if a saint had been converted into an instrument, while the word Ariette (petite…

The first bamboo bow that entered my life never breathed Indian heat; it lived inside a grainy photograph pinned above my crowded desk in Portlaoise, between a postcard of Velázquez and a stained reading timetable. The photograph came from an…

Rome Learns Distance The arrowhead rose from the Mesopotamian soil like a small dark tooth, green under its rust as though it had grown there with the barley. A man in a fluorescent vest and cracked boots—whatever name his century…

The Mane, Sovereign Kingdom of Ebvren (The Barren State), City Capital Vrenki – Typhon Resurgence, Day 10 Whatever Ebvren, and by extension its capital city Vrenki, had to claim in terms of sovereignty, was beyond Fergus Reeves. If it wasn’t…

Late light spills over a summer field that could belong to any stop on the World Cup caravan—air thick as steamed linen in Shanghai, sharp as dry paper in Madrid—and in that blur of geography the camera for Mr and…

November carries a clear marker for The Irish Field Archery Monthly as Issue 48 completes four uninterrupted years of publication, reflection, and field-bred argument. The magazine stands as a continuous conversation between cold shoots and warm rooms, between physical discipline…

Sometime ago I came across a peculiar, and dare I say comical, tid-bit of archery lore. When reading 1411 QI Facts To Knock You Sideways, there came an entry that excited me greatly as it was archery related. In the…

The Mane, Fohalin, Thilso Island Chain, Southeastern Province – Typhon Resurgence, Day 8 I common joke Renata Zeman had heard as a child, when her parents travelled around the countries of the Poet’s Sea, began with, “A Dytrentian, a Maytoni,…

Some men arrive larger than their birthplaces. They carry a heat that pushes maps outward, seeks new borders, stamps a name into the grain of years. When such a figure drops, ordinary endings jar the ear. An unassuming death jars…

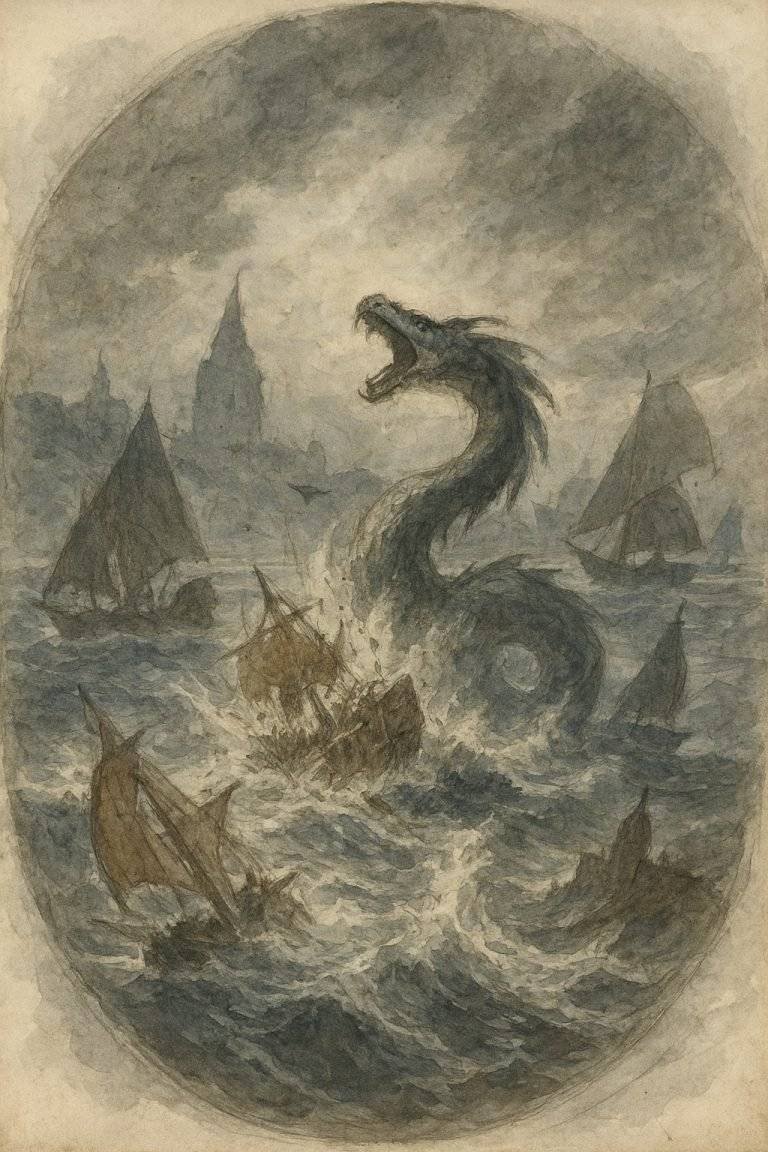

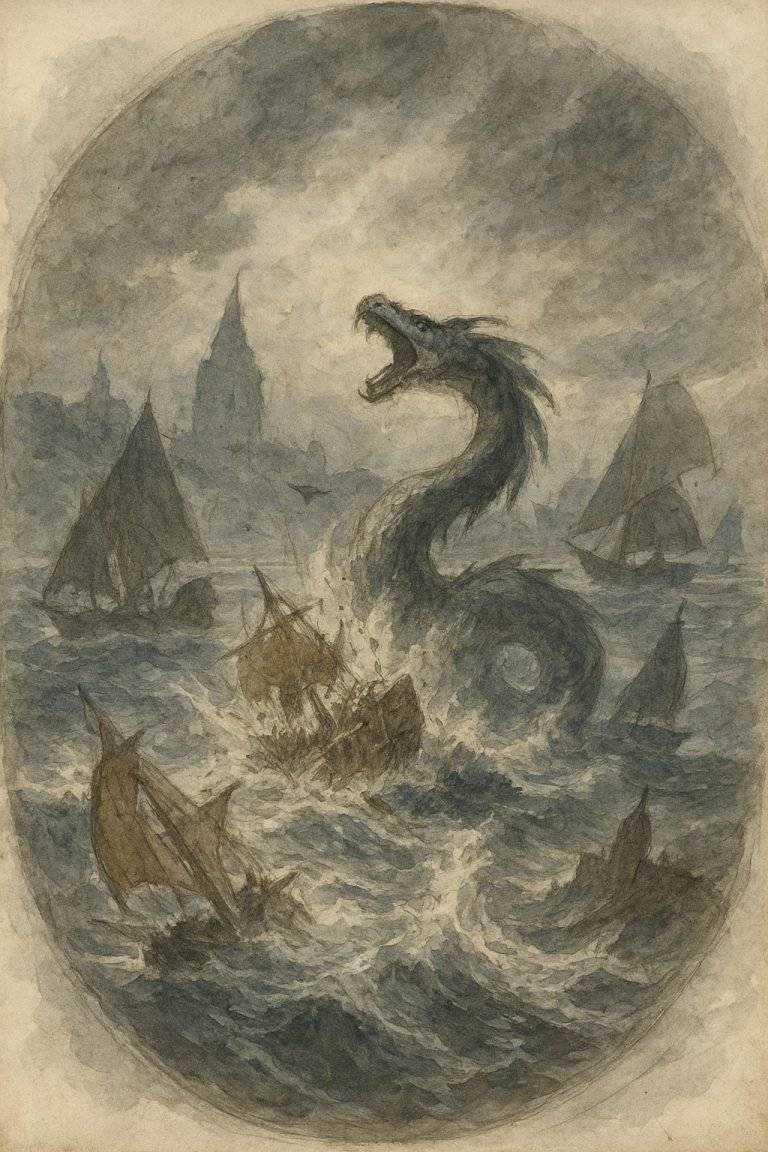

Archers! A new fictional fantasy serial has just begun.

Bowhunter -

The deathly binds keeping a gigantic sea snake, the Vainglory Typhon, at bay have been broken.

Thriving upon its territory for over a century, the citizens of Fohalin, their land, their cities, and their lives are devastated in the wake of the beast's return.

Yet, as the great beast reclaims its territory, it brings with it more than just obliteration.

Fohalin leadership shatters. Left in their stead is an excommunicated Pastoral from a foreign state, an unlucky and ungrateful hunter, and a pirate captain with a conscience who is bound to the will of his ship.

In seeking to cull the titanic creature they are pitting themselves against something that does not need to adapt to its environment, but rather forces the environment to adapt to its presence.

Whilst it is close to Halloween, I would remind the reader, and archer, that zombies, the undead, however you refer to them, are not a seasonal problem. Just as much as a dog is just not for Christmas, a zombie…

I came up with the idea to write this article after reading a message on the club’s chat—one of the fellow archers was curious about horse bows and asked for advice. I liked the brief exchange between him and one…

Knowledge gathers in the hands first. Before theory spreads its mesh, the body enters an agreement with wood, string, air, and ground. A seasoned yew settles into the palm with a weight that carries memory; cool grain moves under the…