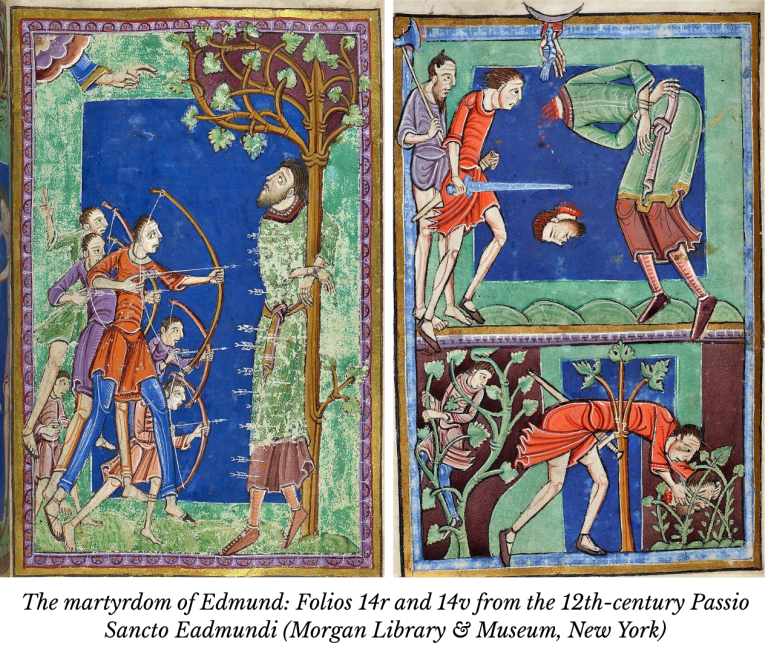

Archers! A new fictional fantasy serial has just begun.

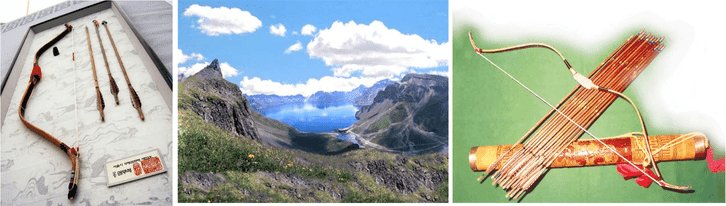

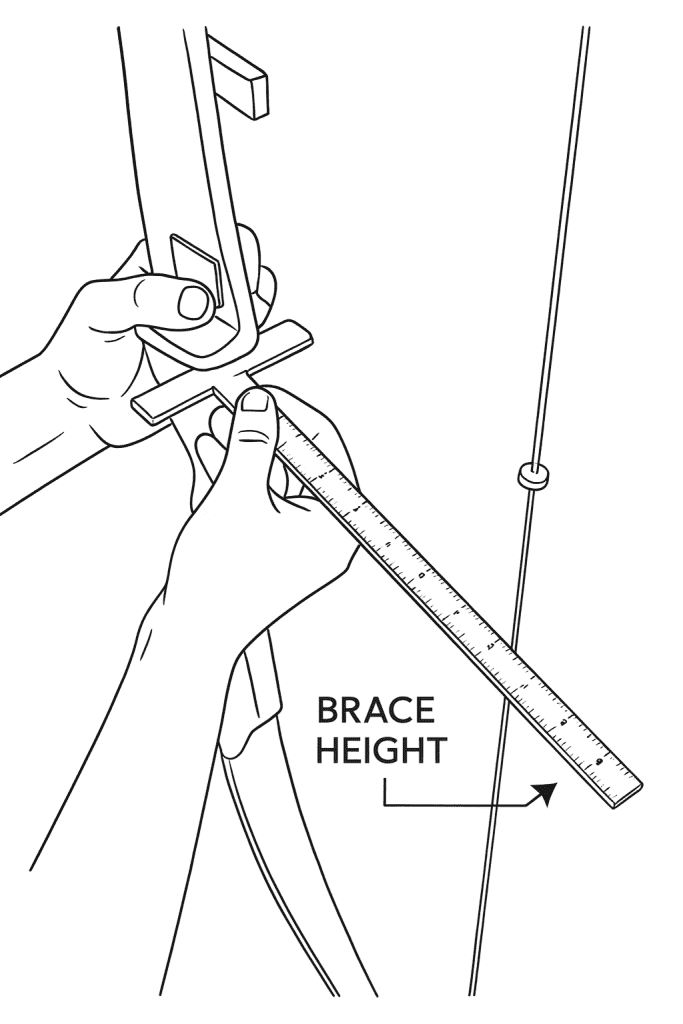

Bowhunter -

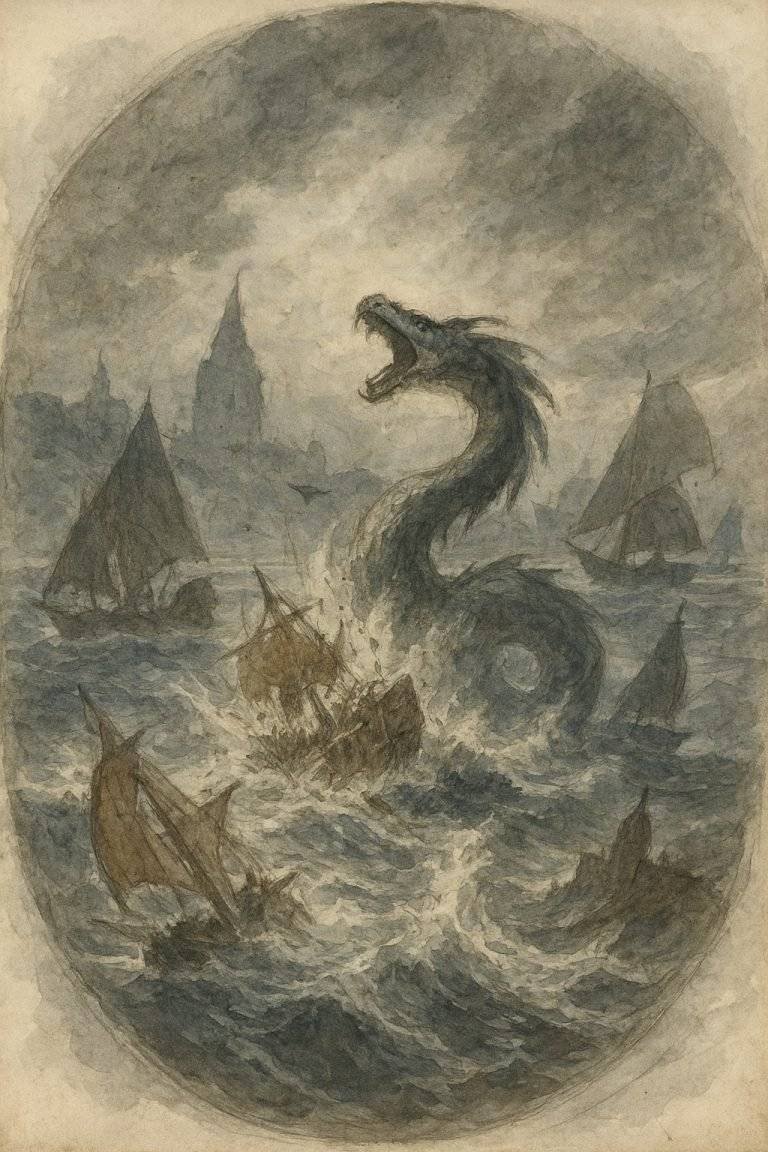

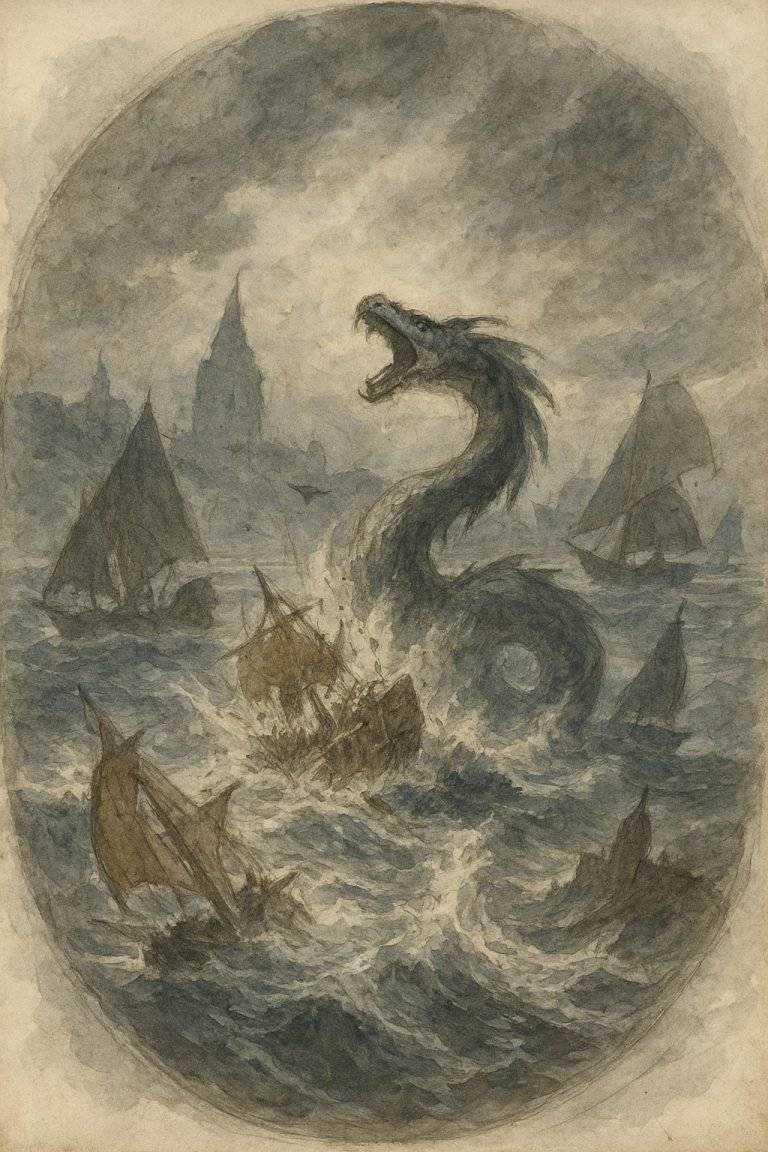

The deathly binds keeping a gigantic sea snake, the Vainglory Typhon, at bay have been broken.

Thriving upon its territory for over a century, the citizens of Fohalin, their land, their cities, and their lives are devastated in the wake of the beast's return.

Yet, as the great beast reclaims its territory, it brings with it more than just obliteration.

Fohalin leadership shatters. Left in their stead is an excommunicated Pastoral from a foreign state, an unlucky and ungrateful hunter, and a pirate captain with a conscience who is bound to the will of his ship.

In seeking to cull the titanic creature they are pitting themselves against something that does not need to adapt to its environment, but rather forces the environment to adapt to its presence.