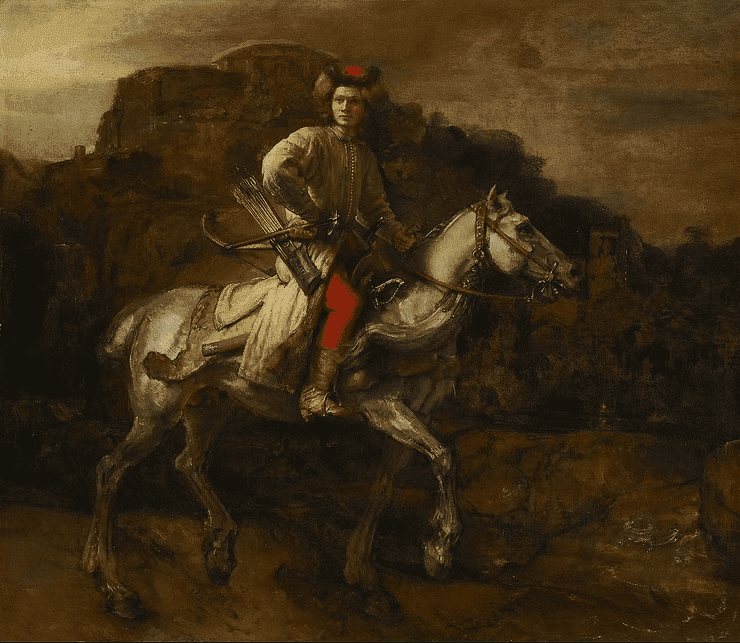

The Lisowczyks formed as a fierce body of Polish light cavalry, carrying the wild spirit of a mercenary host sustained through spoils of conquest. Brought together in 1607 as a soldierly confederation under the command of Aleksander Józef Lisowski, they drew their name from his—his legacy shaping their banner long after his death. Their allegiance lay with the Commonwealth, though coin never reached their hands; sustenance came through spoils alone. They struck into towns and villages across enemy lands, tearing through stone and spirit alike, burning, seizing, and destroying with furious purpose. Churches and monasteries yielded no sanctuary. Their passage carved terror into the lives of the innocent. In the Czech lands, long after the company ceased, mothers carried tales of Lisowszczyks to frighten children into obedience, casting them as creatures of fire and blood, unmatched in malice. Their vanishing defied a single date—by the mid-1620s, they drifted from the field, their once-unique imprint fading into the broader chaos of war.

In form and function, the Lisowczyks mirrored the shape of Polish cavalry from their day. Each unit bore the name of a banner, often numbering between one hundred and four hundred men. These banners gathered comrades—bannermen—and footsoldiers alike. Alongside them rode unattached servants, who, though second in status, frequently joined the fight. Yet a crucial difference marked them from the Polish standard: the Lisowczyks chose their own colonels from within their ranks.

They surged through Europe as the swiftest warriors of their time, rivalled only by the relentless Tartars. In one stretch of daylight, they could cover one hundred and sixty kilometres—four times the range of the most agile forces of the age.