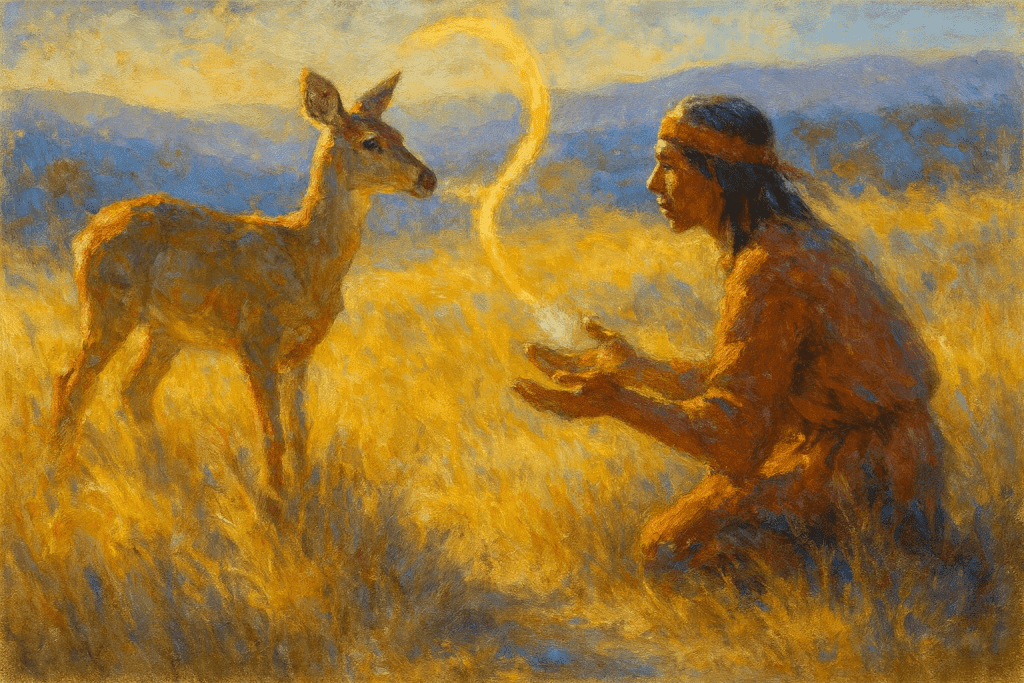

Elders share a winter story from the northern woods. Frost wrote its fine script across alder and birch, and a young hunter walked a corridor of blue light where breath rose like white birds. A doe stood in the hush and faced the hunter with calm eyes that held a country of knowing. The hunter lifted the bow, and the deer spoke across the space in a voice that sounded like river over stones: “Choose kinship or hunger, and shape hunger through kinship.” The hunter lowered the bow, set palm on the ground, and offered a strand of hair, a button, a pinch of meal from a pouch. The doe stepped forward, breathed into the hunter’s hand, and left one slender rib beside the offerings. From that bone came the first whistle for calling, and from that calling came a covenant—the people would eat through an agreement that carried respect in both directions. The deer would give, and the people would give in return, and the land would carry the memory of that exchange in grass, in hoofprint, in human song. Every archery season rises from that early promise: power serves when consent guides it, and meals carry honor when gratitude leads every step.

A writer stands at daybreak and watches an archer along a hedgerow where alder leans toward a field. Cold creeps through wool with sharp gentleness, and the light carries that silvery hue a person feels in the ribs. The archer’s palm slides along the riser as memory guides it; years of habit bring skin and wood into one patient handshake. Breath lifts and turns to milk-white wisps that fold back into the trees, each one a small messenger returning to its sender. Waiting gathers around the body like a cloak. Hearing widens. Sight learns long patience. A faint twig-snap expands into a paragraph, and the light brush of wind across the cheek announces a drift of scent toward the lower meadow. Meaning arrives through every small sign, each one a bead that threads toward a fuller understanding. The whole scene moves with old rhythm, the sort of rhythm that carried families through winters and kept songs alive beside peat fires.

Rifles stretch the world to arm’s length; a bow invites a nearer covenant. This archer steps inside the animal’s sphere and breathes the same cold air, stands in the same frost-glitter, hears the same crow-call. That step changes the nature of the work. Release arrives as a hush, a soft hiss that belongs in this wood alongside wren chatter, stream murmur, and bark creak under thaw. Muscle holds true form; spirit clears to a still pool. Time loosens its tight weave and hangs with spacious generosity. The archer stands within that enlarged hour, present as flame in a lamp. A seasoned power begins to move—steady, unshowy, anchored in craft and long practice—and it carries a gentle authority. Many give that state a contemplative name; woodsfolk speak of the quiet turn inside where mind and place walk together. Peace rises here with a clean pulse, far from roads and rushing talk. The body absorbs a lesson through these hours, a lesson of rightful belonging, and thought later builds sentences around that embodied truth. Physical discipline leads first and lays foundation; understanding follows with weight underfoot and grace in the shoulders.

The circle widens from the drum of individual breathing to the entire life of the grove. Trees, moss, soil, insect, fungus, feather—all join a living council. Aldo Leopold named the land a community, a living order with citizenship. That vision lifts a person from possession toward participation. Hunters accept their place among the members—the rooted, the furred, the winged, the scaled, and the track-reader with a bow. Leopold drew an energy circuit: soil to plant, plant to grazer, grazer to hunter, flesh and bone returning to soil, and the circle continuing with bright resolve. Every creature marks a link in that radiant chain. A deer browsing acorns under oak, a fox cleaving the grass toward a mouse’s heartbeat, an archer at full draw as dawn widens—each one stands inside the same transfer and return. To hunt means stepping into the circuit with consent and clarity. The act welcomes a role, affirms a lineage, and declares accountability in the movement of life from one being to another. Recognition of that role matures into what Leopold called an ecological conscience—a responsibility felt as surely as hunger, as surely as the weight of a haunch across shoulders during a long walk home. Philosophy climbs down from the page and stands ankle-deep in leafmould; thought carries mud on its boots and a lawful joy in its chest.

Responsibility fills the pack now with honest heft. These hills carry a different music from the days of our grandparents. Wolves once framed ridge lines with their amber gaze, and tawny cats threaded ravines where dusk settled early. Their departure reshaped the choir of the place, and deer multiplied beyond the appetite of the ground. A browse line rings the thickets like a tide mark, as precise as a muzzle’s reach. Understory thins where hooves return too often. Spring ephemerals invite longer searches, and low-nesting birds shift their songs to altered shelter. Saplings lift themselves and meet eager mouths. A balanced world once relied on fang and claw for constant editing; present fields call upon a different editor with a two-legged stride and a mind tuned to community health. Each bioregion—these waters, these stones, these hedges of hawthorn and ash—reveals a specific arrangement. Living as a native of place means embracing the role that local conditions ask from residents who cherish continuity. Bowhunting rises as a steward’s craft within this context, a tool shaped for renewal as surely as for harvest.

A license fee travels beyond paperwork and enters the woods as trail cameras, population studies, and careful counts by biologists who love these groves with a scholar’s patience. The modern human predator occupies a conscious station. A wolf answers its gut with honest vigor; a person carries an ethical map across the ribs and hunts for the good of neighbors who wear hoof, wing, and bark. That mindset asks for restraint, placement, season, and scale. The decision to draw, the decision to hold, the decision to lower the bow—this triad forms a civic practice as much as a personal one. Integrity of habitat, stability of populations, and beauty of living order rise together as a triad worthy of loyal service. Service to that triad defines a wild ethic.