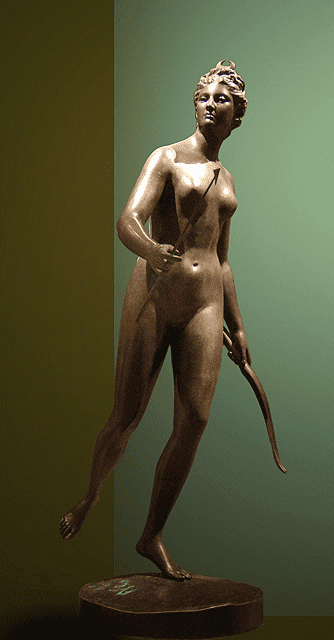

Lecture on Houdon’s Louvre Diane, where toe-balance and a crescent seam make chastity a crafted law.

What runs on a single toe yet makes your own feet grow heavy; what bares a body yet tightens a law; what offers a moon in the hair yet smells, in the mind, of charcoal and hot metal?

I met Houdon’s Diane in the Louvre at an hour when the galleries carried the murmur of school groups and the softer murmur of couples who kept their hands close, as if marble floors held a charge. The guard stood by the threshold with his weight settled into one hip, the posture of a man whose bones had learned corridors. A listener beside me, young, city-bright, shopping bag creased at the handles, shifted her stance in small restless measures, as though the bronze had lent her its forward itch. My own knees answered more slowly, with the stubborn tempo of age and old injuries, yet the answer came, and it came in flesh before it came in thought.

The plinth carried the maker’s mark on the left, HOUDON.F. 1790, cut into metal with the confidence of a seal on wax, and the Louvre’s collection record fastened the figure to inventory, measure, sale, inheritance, acquisition, those secular sacraments that museums keep with a devotion priests once reserved for baptismal books.¹ I read the label and then I looked away from it, and the facts remained in the soles of my feet, heavy as coin in a pocket. A work of art lives in ledgers as well as in limbs, and the ledger’s weight can change the gait of the living viewer.

Scale arrived as argument spoken in numbers. The museum gives 1.929 metres from sole to crown and 2.06 metres as the lifted arm claims the air, with a depth about 1.145 metres, and that depth matters, for the figure behaves less like an image and more like a corridor that asks the viewer to move. The torso’s thrust asks for distance, then the head draws the viewer close again, for Houdon shaped the face with the sting of portraiture: eyes that keep their focus, cheekbones that carry the pressure of living skin, mouth closed with a discipline that refuses panting. The bronze reads life-size and larger-than-life at once, a person poured into metal with an idea poured above the person.

Bronze carries colour as temperament. In the hollows under collarbone and along inner thigh the metal gathers to brown-black; at the bow and hip a warmer tone rises where hands have brushed the surface across decades; under hard light a brief flare shows, yellowed like old coin, then folds back into dusk. Patina keeps contact as memory. It holds the touch of strangers who wished for a share of the goddess’s certainty, and it holds the museum’s own slow commerce, the invisible trade of attention, the daily exchange in which bodies pay with time and receive, in return, a lesson.

Close looking yields labour. Along the outer line of the right calf the bronze runs smooth enough to pass for flesh; inside that same calf, near the knee’s hinge, fine parallel striations appear, minute planes laid by rasp and softened by chase. A seam rides a contour and slips under polish with the modesty of a confession that reaches the throat and finds a swallow. In that swallow the workshop appears: charcoal breath, crucible heat, clay moulds carrying their earth smell, hands that know weight and risk, the small violence of tools moving across a surface until the surface begins to imitate life.

The crescent moon in the hair draws the eye as emblem of vow and night-rule, a small sign that takes the place of cloth, and raking light reveals a faint casting line along the inner curve, a hairline scar that flashes and fades as the viewer shifts. That line changes the emblem. The moon ceases to live as pure symbol and begins to live as join. Join implies division and repair, a discipline of making. The goddess’s chastity moves from natural innocence into workmanship, maintained by decision and by care, as though a vow lived as a finished surface that keeps its wound in plain sight.

A listener might answer with a shrug that casting yields parting lines in every age and every foundry. The truth stands. Yet Houdon chased long passages into continuity across abdomen and front thigh, and within that context the line on the crescent reads as a kept whisper at the emblem’s ear. The sculpture’s scandal turned upon nude exposure in civic view, and the crescent served as clause and alibi, so the seam carries evidential weight, a thin proof of the labour that props the law. I watched the seam flare and soften and flare again, and the flare behaved like conscience, returning as soon as attention wandered.

The body of the viewer meets the law through the toe. Diane advances on the point of the left foot, a feat that a record in the Galerie des moulages at the Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine states with plain French clarity: elle avance en prenant appui sur la pointe du pied gauche.² The phrase sounds like an engineer speaking of load and pressure, yet the phrase lands in flesh. My stance sought the comfort of a full sole; the bronze accused that comfort. I rocked forward and felt the calf begin to burn, and the burn carried a private humiliation, the sort a man feels when a younger body shows him his own heaviness.

The spiral composition carries that strain up the body. The torso winds from toe through hip into ribs; the head turns away from the direction of travel, so pursuit and vigilance share the same spine. A quiver rides the back like a burden; its strap crosses the chest with the frankness of working tack. Stone demands compromise, and the marble at Lisbon carries supports at the base, plants that serve as extra points of contact, a botanical architecture that props speed against gravity, as the Gulbenkian record makes clear in its technical attention to the marble’s needs.³ Bronze permits a bolder lie, a balance that looks almost effortless, yet effort lives inside it, hidden in distribution of weight and in the geometry of the base.

The nude body sharpens the wager into ethics. A huntress goddess in full motion and full exposure presses against an older decorum that asked for some drapery, some veil, some softening of the public gaze. The Huntington’s account of the 1782 bronze commissioned for Jean Girardot de Marigny speaks with polite directness: the huntress wore only a crescent moon in her hair.⁴ A body offered to view under the authority of antiquity draws desire and then turns desire into distance, for the face refuses frenzy, the mouth stays closed, the eyes keep their alert calm. The erotic charge lives in the flesh; the civic command lives in the expression, and the viewer stands caught between them.

The room cooperated with that command. A schoolboy raised his phone and the guard’s eyes met him at once, steady as a parish clerk’s gaze when a drunk begins to sing in the aisle. The boy lowered his hand and pretended interest in a nearby bust. The young woman with the shopping bag shifted again, and her shoulders squared as though the bronze had given her a lesson in posture. My own hands hovered, foolishly, as if touch could translate sight into certainty, and my hands then fell back to my sides under the museum’s tacit rule.

—You watch her every day, I said, keeping my voice low.

—Every day, he said, and his consonants carried the flatness of long hours—people change in front of her.

He spoke as a witness, and witnesses belong to courts. That felt fitting. Diane holds a tribunal in silence, and each viewer arrives as defendant and juror in one body, presenting the face of civility while the private mind runs its own chase.

Paper holds the first uproar. A record in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, preserved in the Deloynes collection and tied to Mathieu-François Pidansat de Mairobert’s chronicle of Parisian life, points to writing on the plaster shown in 1777, a trace of scandal and argument held in ink and shelfmark.⁵ A text like that binds sculpture to talk, to moral temperature, to bodies gathered in a public sphere that treated art as theatre and judgement as entertainment. I imagined the Salon crowd in powdered hair and tight coats, shoulders pressed together, voices sharp, virtue worn as a badge and desire worn as a secret, all of them looking at a huntress whose nakedness carried the authority of myth.

Biography brings pressures tangible as keys in a pocket. The Metropolitan Museum’s essay places Houdon’s early life in Versailles, close to the Bâtiments du Roi and the École des Élèves Protégés through his father’s concierge post, a corridor-life that made casts, institutions, and ambition part of a child’s air.⁶ A boy raised among rules and models grows into a man whose goddess carries rule in her balance. Archival grit deepens the point. Ernest Gandouin transcribed baptismal detail and family shifts, showing the maker tethered to parish record and to ordinary labour, a life anchored in signatures and dates, as concrete as a chisel in a palm.⁷ The story reads in ink and paper, yet the story also reads in bronze seams, for a life among keys and classrooms can produce a mind that understands discipline as beauty’s twin.

Yet biography alone makes poor theology. A sculpture speaks through its own formal decisions, and those decisions carry cruelty and tenderness in the same breath. Houdon knew anatomy with the intimacy of a man who has watched flesh in studio light and translated it into clay and plaster and marble. He kept Diane’s ankle slender, he kept the risk visible, he asked bronze to bear faith. A lesser hand would thicken the joint and smooth away danger; Houdon preserved fragility and made fragility persuasive. The risk feels erotic as exposure; the risk feels metaphysical as trust, for balance on a point asks the world to hold.

Scholarly synthesis gives the object its family tree. Anne L. Poulet traced variants, patrons, and versions across marbles, bronzes, reductions, and later casts, so a surface detail can be tested against a kinship of bodies beyond a single glance, measured against a single room.⁸ That method turns the crescent seam into a question that can travel: a line chased away in one version and preserved in another speaks of choice, workshop practice, and later taste. A catalogue can feel like dry bread, yet bread keeps a mind alive, and it keeps a claim tethered to objects.

The workshop itself carries politics. Studies of French bronze casting in the long eighteenth century show authorship entangled with specialist labour, with founders and chasers and patineurs, with secrecy and status, with a market that priced skill as surely as it priced marble.⁹ The seam on the crescent moon belongs to that world. It serves as emblem and as signature of hands. In a culture that praised clarity, the foundry kept guarded arts, and the goddess’s scar offers a small leak of truth. The smell of charcoal and hot metal lives in the mind as soon as the seam enters sight, and the mind supplies the rest: wet clay, ash on sleeves, the hush that falls when molten metal begins its pour.

I circled the figure as one circles a wary animal. From the front, Diane reads as thrust: the line from left hand through bow to forward knee forms a spear-like insistence; the lifted heel of the right foot creates suspension, a beat held in metal. From the side, breath enters through the open ribcage and rotated shoulder; tension travels like a drawn string. From behind, quiver and strap turn the nude body into a working body; the strap presses into flesh with the logic of friction; the back muscles suggest scapula sliding under skin. The sculpture refuses a single privileged angle. It demands circumambulation, and the demand turns viewing into a bodily rite.

The guard watched the circling with the patience of a man who has seen every kind of reverence. Some viewers walked fast, hunting selfies; some walked slow, hunting thought; some stood fixed, as if motion belonged to others. I saw a child place a palm on the barrier rope and lean forward; I saw an older man close his eyes as if prayer lived in darkness; I saw two friends whisper and laugh and then grow quiet as the nude body asserted its law. The bronze gathered these human acts into its orbit and held them, the way a forest clearing holds voices for a moment before the wind carries them away.

Diderot understood that orbit as moral action. In the Salon writings he treated viewing as theatre in which bodies gather, judge, desire, and perform reason through posture and speech.¹⁰ Houdon’s goddess turns that theatre against its audience. She embodies classical authority and reveals mechanics of making; she offers desire and orders distance; she offers speed and holds time in arrested metal. The crescent seam functions as the smallest prop and the deepest cue, for a sign of chastity carries a scar, and a scar speaks of joining, of labour, of time.

Myth provides older violence that sits inside chastity like a blade in a sheath. Ovid tells of Actaeon, whose gaze meets Diana at her bath and whose punishment arrives through transformation and hounds, a lesson in the danger that follows sight.¹¹ Houdon shifts emphasis from bathing to pursuit, from vulnerability to sovereignty, yet the seam reintroduces vulnerability at the level of making. A scar lives in the emblem. A vow lives as maintenance. A goddess lives as constructed object, and construction implies damage, repair, exchange, possession. The museum turns exchange into public trust; the seam keeps the memory of the earlier world in which bodies in bronze travelled as trophies of taste.

My own childhood carried myths of another coast. In Irish fields a hare could carry a witch’s spirit, my grandmother said, and a man who chased the hare too long would find his own breath torn from him by the chase. In Polish villages, so the old book I once read in Łódź claimed, a hunter who broke taboo at a river would find his bullets bending away from their prey, as if the world itself defended its rule. Those folk tales share the same logic as Actaeon’s: looking and chasing carry moral consequence. Houdon’s Diane belongs to that logic, even in the Louvre, even under glassy modern lighting, for the viewer’s gaze meets a law that comes clothed as beauty.

Taste in the eighteenth century carried its own creed. Winckelmann’s history of ancient art taught Europe to crave noble simplicity and quiet grandeur, and that craving shaped academies and patrons and the language of critics.¹² Houdon worked within that creed while he tested it, for the seam insists on workmanship inside ideality, heat inside moonlight, labour inside law. Classical serenity receives its birth in a furnace, and the furnace leaves a hairline mark that a viewer can read with the right angle of head and the right patience of eye.

Education and discipline press the point further. Rousseau shaped the child in Émile as a creature whose virtue grows through habit, through the training of senses, through social choreography that turns posture into destiny, and his pages carry a fascination with the body as moral instrument.¹³ Diane stands as sculpture of that fascination. Her toe-balance teaches the viewer through muscle, and the lesson yields a small shame, for the viewer discovers how easily beauty becomes command. The calf burns, for the sculpture persuades the body to imitate what it sees, and imitation opens the door through which law enters.

Kant gives the paradox its philosophical frame. In the Critique of Judgment he writes of beauty as a felt lawfulness that seems free, a purposiveness sensed in form, a pleasure that carries quiet legislation, and the idea lands in the Louvre with a bodily force that theory alone seldom achieves.¹⁴ The goddess appears free in motion, yet the viewer’s feet shift, the viewer’s gaze measures distance, the viewer’s desire meets an impassive face, and the crescent moon shines with a scar that binds purity to making. The law arrives inside beauty, in the same breath as it.

The young woman beside me finally gathered her weight forward, calf tight, chin lifted, and for a second her body echoed the bronze’s insistence. The shopping bag hung from her fingers like a city quiver. Her eyes held the goddess’s face. Her blink came slow, as if the room had asked her for a vow.

—She runs, she said, voice softened by surprise—yet she stays.

Running held itself inside fixed metal, and fixed metal trained living bodies into motion of a different kind: circling, yielding, recalibrating stance. The crescent seam returned in my mind again and again. Purity ceases to live as nature and begins to live as workmanship. Law ceases to live as text and begins to live as finish. Nations, churches, parties, households praise purity, and hands work in the background to enforce, repair, polish, conceal. The seam makes that background visible in a line thin as a hair, and the visibility carries a moral sting, for it shows how often restraint takes its first lesson from beauty.

Now the riddle yields its answer in the room’s air. The creature that runs on a single toe and makes your feet grow heavy lives in bronze, and it teaches the body through strain that feels like sympathy. The body that bares itself and tightens a law belongs to Diana and belongs to the civic crowd that learns restraint in the act of looking. The moon in the hair carries a seam, and that seam carries the wager: purity arises through joining, through workmanship, through scars polished until they gleam. Houdon’s goddess carries speed, yet the speed carries the slow truth of making, and the truth keeps hunting the viewer, returning to the inner curve where metal met metal and a hand left the trace—

Scholia:

¹ Musée du Louvre, Département des Sculptures, Diane (inv. CC 204; N 15496), bronze, signed “HOUDON.F. 1790,” collection record and provenance (Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2022). The museum record reads like civil scripture: measures, sales, heirs, accession. Each line names a moment when the huntress lived as property, when a body in bronze carried a price and waited for a buyer. A date such as 8 October 1795 places the object in a room of commerce among voices that weighed taste against cash and reputation. The later sale in December 1828, followed by acquisition in January 1829, marks another crossing, from private residue of an old regime into public authority. Such facts resist romance, yet romance feeds on them. A sculpture that seems to outrun time in the gallery moves through time in ledgers, and the ledger leaves its own stain on interpretation. The signature on the plinth at the left also matters. It meets the viewer mid-circuit, low and firm, a maker’s name offered as evidence, with boastfulness left outside.

² Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Galerie des moulages, Diane chasseresse (moulage; plâtre patiné), inv. MOU.01133, collection record (Paris, Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, 2021).

³ Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Diana (inv. 1390), marble, Paris, c. 1780, collection record and provenance (Lisbon, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2023).

⁴ The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, Diana the Huntress (Jean-Antoine Houdon), bronze, 1782, collection label and commission context (San Marino, The Huntington, 2019).

⁵ Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, manuscript record for “Exposition d’une Diane chez monsieur Houdon,” attributed to Mathieu-François Pidansat de Mairobert (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, catalogue record). A shelfmark carries an ethic, for it gives a path from assertion to paper and from paper to a hand that moved in a living room of judgement. The Deloynes compilation preserves the simple fact of discourse around the plaster in 1777: a work of sculpture drew language, heat, defence, mockery, desire. That preservation changes what a later reader can claim. A sentence in a catalogue can point to a folio; a folio can yield the cadence of a witness; the witness can reveal how a Paris crowd weighed nakedness, antiquity, and civic decency. The manuscript form matters as much as the content. Ink, margins, binding, and the labour of keeping form a second history alongside the bronze and marble histories. Such archival survival lets a scholar treat reception as material fact, with rumour left to drift through later criticism.

⁶ “Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828),” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008).

⁷ Ernest Gandouin, Quelques notes sur J.-A. Houdon, statuaire, 1741–1828 (Paris, Nouvelle Imprimerie, 1915).

⁸ Anne L. Poulet, Jean-Antoine Houdon: Sculptor of the Enlightenment (Washington, DC, National Gallery of Art; Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum; Versailles, Château de Versailles, 2003).

⁹ Geneviève Bresc-Bautier and Guilhem Scherf (eds.), Bronzes français de la Renaissance au Siècle des Lumières (Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2008). Bronze forces confession. A marble figure can pretend to solitary making, yet bronze calls for a chain of hands: founder, chaser, patineur, supplier, patron, carrier. The chain forms the medium’s truth, and scholarship on French bronzes gives that chain names and roles, placing authorship inside labour and commerce. In that frame a seam becomes more than blemish. A seam signals a meeting of parts, a decision about finishing, a negotiation between time, cost, skill, and pride. The crescent moon seam in Diane’s hair gains its sharpness through this context, as the emblem of chastity also acts as a witness to workshop reality. A culture that praised clarity and reason still relied on guarded skills and tacit knowledge. A line on bronze can carry that tension as plainly as any philosophical page.

¹⁰ Denis Diderot, Salons, ed. Jean Seznec and Jean Adhémar, 4 vols (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1957–67).

¹¹ Ovid, Metamorphoses, ed. and trans. (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004), Book III.

¹² Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (Dresden, Walther, 1764).

¹³ Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Émile, ou De l’éducation (Amsterdam, Jean Néaulme, 1762).

¹⁴ Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft (Berlin, Lagarde und Friederich, 1790).

This article is part of our free content space, where everyone can find something worth reading. If it resonates with you and you’d like to support us, please consider purchasing an online membership.