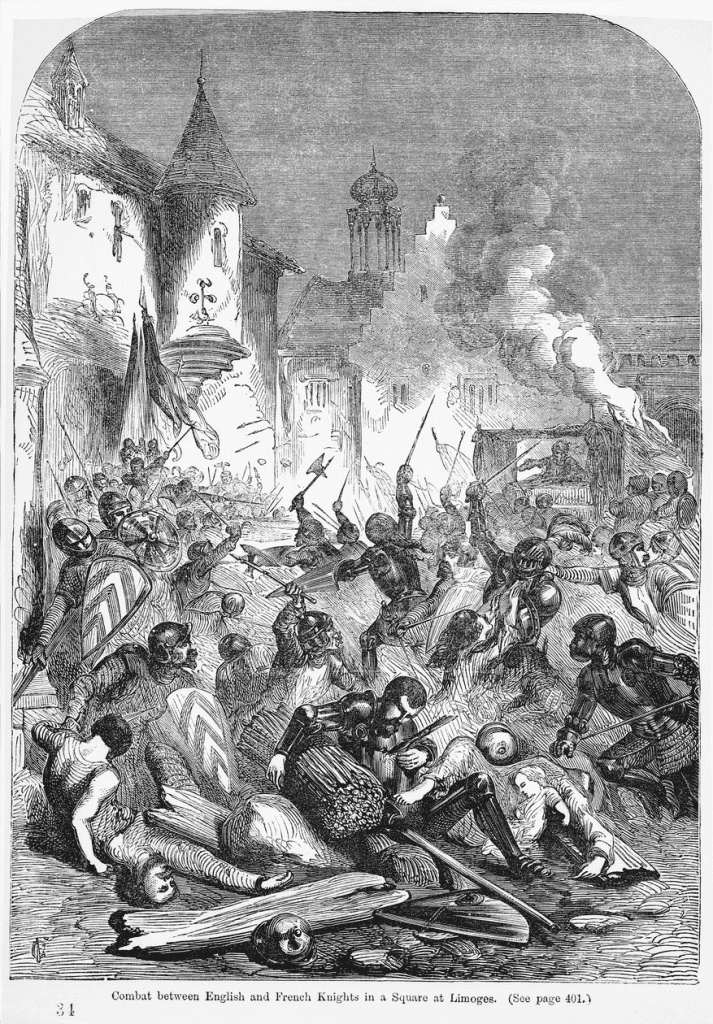

Dust deepened within the breach while heat raised a chalky veil from crushed ashlar, and a litter advanced in a long, breathing sway as four shoulders moved with choir-like discipline and the poles sang against their leather slings. Fever pressed a fine edge along the prince’s sightline, which guided his attention across the ragged seam where props had burned and mortar had yielded, so he read the fracture as a joiner reads a wounded joint and weighed the angle that would admit men and consequence. Edward of Woodstock came up to that gap in September 1370 with a name already weighted by Crécy and Poitiers, with a principality whose coin rang beneath his seal at Bordeaux, and with a frame that demanded bearing hands while his will traveled a half-pace ahead of the men who carried him.¹

Years of campaign and council had laid down habits stronger than sinew, which meant that each choice on the field already bore the shape of assemblies and ledgers. In Aquitaine he gathered Estates at Angoulême and at Saint-Émilion, where breath warmed wax and parchment while fouage rose through argument and assent to feed garrisons, bridges, and castles; in those rooms he learned how fiscal speech binds a province with a grip equal to that of spears. He impressed authority upon letters that named towns, dates, and obligations with a clerk’s exactness and a captain’s cadence, so every courier carried policy as well as paper. Triumph in Castile delivered laurel and debt in the same moment and carried an inland consequence into the chamber, since a flux in the gut and a swelling of the limbs demanded draughts from physicians and altered command into a rhythm that joined an hour on horseback to a day upon the litter. The office therefore hardened even as the body softened, and that exchange sharpened judgment, since private endurance drove public resolve.²

Across the valleys a second intelligence answered with patience that favored sieges, withdrawals, and councils over sudden shock. Charles V governed through ordinance and measured pressure, so his war moved by charters, oaths, and garrisons that watched roads and rivers, while Bertrand du Guesclin schooled captains to spend time as coin and to win through conservation. Inside that temperature, Jean de Murat de Cros—jurist by training, bishop by dignity, brother to Pierre who held the papal chamber’s keys—stood as a hinge between cathedral and court, since kinship with Avignon widened a man’s reach across frontiers. The duke of Berry entered Limoges under that canopy of counsel, and the gate yielded with a turn that cut deeper than mere alignment, since the prince had advanced Jean de Cros in former years and had counted trust as a currency inside his Aquitanian house. A gate that opens by friendship teaches a harsher lesson than one opened by force; the message spreads along valleys faster than heralds.³

The city itself approached the army as a double body that kept two hearts in one ribcage until policy forced a discord. Around Saint-Étienne, the bishop’s Cité gathered lanes, stalls, and courts under ecclesiastical jurisdiction that traced its own arc of custom and revenue; around Saint-Martial the Château quarter sustained a market’s older pulse and the memories of viscomital and royal right. A short walk linked the two while a gulf of law divided them, so the breach of September gaped chiefly inside the bishop’s precinct—the very fabric that had swung to Valois counsel—while the market-city across that brief distance continued under the prince’s orbit into the following year. Geography therefore shaped meaning, since ruin gathered in one jurisdiction more than the other, and the map supplied a gloss that readers often mislay when a single flame appears easier to remember than paired embers that smoulder at different heats.⁴

Notes:

1 Richard Barber, Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine, Boydell, Woodbridge, 1978, pp. 12–14; Michael Jones, The Black Prince, Head of Zeus, London, 2017, pp. 61–67.

2 Richard Barber, Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine, pp. 178–203; Michael Jones, The Black Prince, pp. 214–233.

3 Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, Vol. I, Libreria Regensbergiana, Münster, 1913, p. 24; Guillaume Mollat, Les Papes d’Avignon (1305–1378), Letouzey et Ané, Paris, 1912, pp. 349–352.

4 Guilhem Pépin, “The Sack of the ‘City’ of Limoges (1370) Reconsidered in the Light of an Unknown Letter of the Black Prince,” The Journal of Medieval Military History, XXI, Boydell, Woodbridge, 2023, pp. 161–180.

5 Philippe Contamine, Guerre, État et Société à la Fin du Moyen Âge, Mouton, Paris–The Hague, 1972, pp. 196–205.

6 Jean Froissart, Chroniques, ed. and trans. Thomas Johnes, J. Barfield, London, 1803–1805; selections in J. C. Holt (ed.), Froissart in England, Boydell, Woodbridge, 1968, II, pp. 61–68.

7 Jonathan Sumption, The Hundred Years War: Divided Houses, Faber & Faber, London, 2009, pp. 82–85.

8 Adrian Ailes, “The Origins of the Royal Arms of England,” in Adrian Ailes & Malcolm Mercer (eds.), The Heraldry, Politics and Identity of Late Medieval England, Shaun Tyas, Donington, 2000, pp. 1–24.

9 Barbara Harvey, “The Black Prince’s Chantry at Canterbury,” Journal of the British Archaeological Association 131 (1978), pp. 73–97.

10 Anthony Goodman, John of Gaunt: The Exercise of Princely Power in Fourteenth-Century Europe, Longman, London, 1992, pp. 19–42.

11 Gaston Fébus, Le Livre de chasse, ed. Gunnar Tilander, Paris, 1936, Introduction and Book I, for princely ethos and method.

12 John P. O’Neill (ed.), Enamels of Limoges 1100–1350, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1996, pp. 3–15, 226–231.