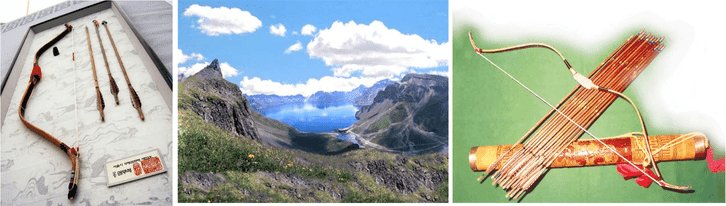

Wind travels down from Baekdu’s crater lake in thin blue bands, crosses volcanic scree, the larch forests, the rice fields, and enters the peninsula with a faint taste of stone and snow; along that wind, for millennia, arrows have flown. Korea remembers itself as a country of the bow: mythic kings such as Jumong and Bak Hyeokgeose receive their first aura through extraordinary marksmanship, while later dynasties expect every soldier, and many scholars, to prove themselves with horn bow and bamboo shaft. Language itself bears the imprint; old texts gloss hwal as the native word for bow, explain that “to shoot” becomes hwal-sswae, and record how Chinese chroniclers, gazing eastward, joined the characters for “great” and “bow” to name the peoples they called Dongyi, those eastern archers whose short powerful weapons fed both tribute and fear. In modern Seoul, composite horn bows hang in archery clubs, children learn Olympic recurve technique at school, and the state treats traditional hwal-ssogi as a form of living heritage, a martial art that still sends bamboo-string twang over glass and concrete toward the surrounding hills.

Out of that long, wind-bruised habit of bows and arrows, two figures step forward with very different weather walking at their shoulders. One of them, Bae Sang-yeol, came into the world by way of Dalseong in the early nineteen-sixties, a small boy whose first lungsful tasted of river fog and the sour-sweet breath of orchards. Soon enough he trailed behind his father up toward Seoul, watching as furrowed fields and stone-stitched paths slid away behind the bus window and the world tightened itself into concrete alleys, squat roofs, a factory light that pretended to be a second, sleepless sun. In that city he slipped down into the technical belly of a big newspaper, among steel ribs and humming ducts, air-conditioning that came cold along his shoulders, presses below that hammered their iron heartbeat so steadily that, on some nights, the whole building felt like a single tired animal breathing ink. Little by little those machinery rooms bent sideways into his own half-secret library. While colleagues dozed between shifts on plastic chairs with their jackets over their faces, he stayed awake, fingers blackened with pencil dust, following war chronicles, envoy journals, reports of fleets edging along winter coasts, embassies inching over snow passes, columns dragging themselves through river-cold mud. He kept redrawing the peninsula in the margins until his notebooks looked like weather charts of invasion and retreat. Years of that hidden, half-paid work straightened him into the line of an independent historian: the man who later sent out thick volumes on Yi Sun-sin, on Goryeo embassies, on forgotten forts and sea walls, all driven by the same stubborn nerve that keeps a press line thudding through the small hours—an instinct that machine and destiny share one wired nervous system.

Views: 3