Room 044 in the Museo del Prado carried a disciplined brightness, the sort a ministry might approve, as the building’s stone drank the street and returned it as a pale, steady radiance. I stood where the wall surrendered to Titian’s Venus y Adonis—1554, oil on canvas, 186 × 207 centimetres—hung at a height that set the spine into attention, large enough to resist the casual glance that tourists toss like small change.¹ The canvas behaved as a body confronted by another body: horizontal, intimate, sovereign, and charged with a decision that had already begun to move.

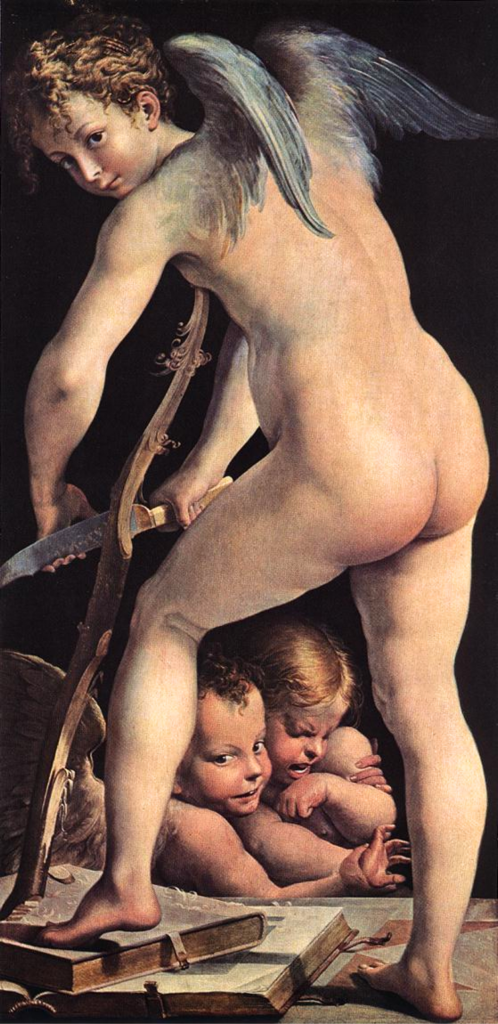

Venus sat with her back toward me, her torso twisting as her arms gathered Adonis into an embrace that carried pleading and possession in one tendon. Adonis leaned toward departure, knee forward, foot set, spear raised as though intent could harden into an oath. Dogs strained at the right edge, their bodies tightened toward a hunt already slipping beyond the frame. Cupid lay under trees to the left, his small limbs given to sleep, his bow and quiver suspended above him like tools hung in a shed after labour. High at the right, a chariot drawn by swans cut the sky, and beams fell toward the lovers with the belated urgency of grace.

My legs learned the painting’s law. At three or four metres, the composition locked into a mechanism: the spear’s vertical insistence braced Venus’s diagonal back, while the dogs dragged the whole rectangle rightward, so motion itself felt like a moral claim. At a metre, surface asserted its own creatureliness. The sky lay thin, so weave and preparation spoke through the blue as though heaven carried grain like breadcrust. Venus’s flesh rose in thicker paint, ridged where brush lifted and returned; light caught on those tiny escarpments and turned illumination into a tactile event. Adonis’s red drapery sat dense and weighty, velvet and blood sharing one pigment economy. Around the trees, darker sweeps carried traces of rag-work, perhaps finger-work, the shadow’s core holding a knuckle’s pressure inside the paint film.

A man beside me, Irish by the vowel and Spanish by the jacket, leaned in as though confession required proximity.

—That red holds its power after centuries—he said, and his voice carried the hushed excitement of a parishioner naming a miracle.

Technical study has given names to what the body already knew. Prado scholarship connected with these early poesie has reported tracing transfer in key elements, pentimenti around Venus’s profile and Adonis’s torso, and thin sky layers that allow preparation to breathe through the paint.² Tracing spoke of workshop intelligence and royal schedule; pentimenti spoke of judgement arriving mid-flight, as the painter revised the emotional engine after the outline had already taken its place on cloth. I leaned toward Venus’s shoulder and felt that revision as a pulse under the surface, the ghost of an earlier decision remaining beneath the final one, a conscience left visible in underpainting.

Views: 7