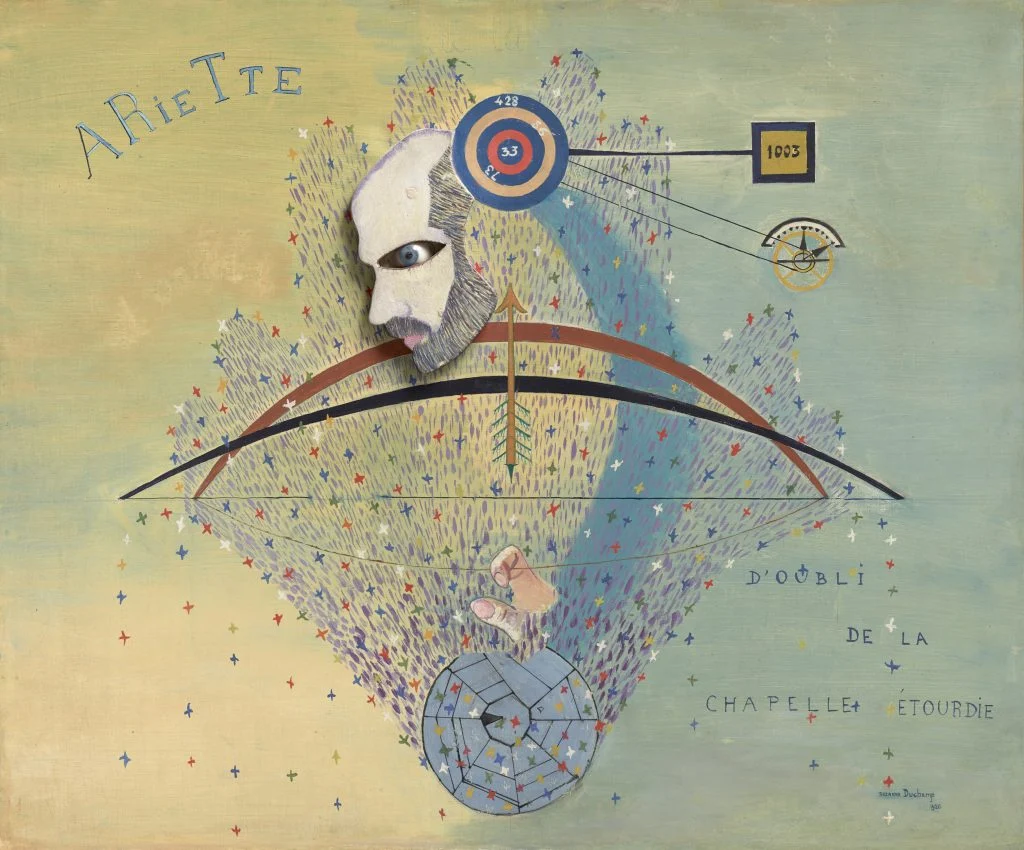

A pale field, washed like chapel plaster after incense has settled, holds its own weather, and in that weather a severed head—half mask, half reliquary—floats as if a saint had been converted into an instrument, while the word Ariette (petite aria) arcs at the upper left with the airy confidence of a tune that enters the ear before doctrine can marshal its arguments.¹ The eye, painted an impossible blue, stares past us with the fixed attention of someone hearing a melody inside a room that has lost its organ, and the beard, drawn in fine hatchings, feels like a curtain of wire through which speech must pass. Around the head, coloured crosses and flecks fall like confetti after a civic parade, though they also read as particulate matter suspended in air, and beneath them two broad arcs—one dark, one reddish—span the width like a bent stave, like a vault sprung from wall to wall, like the bow of a ship whose prayer has turned into measurement.

Suzanne Duchamp worked in a family where invention carried the force of inheritance, and where each sibling, by choosing a medium, chose also a mode of dissent, since the Duchamp household offered both craft discipline and a sly impatience with pieties of finish.² Marcel’s provocations and Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s sculptural engineering created a horizon in which objects could become arguments, while Suzanne, trained in painting’s habits, learned to make images that behave like diagrams of feeling, so that lyric and apparatus share a single breath.³ When she moved through the Parisian circles that braided Cubism into Dada’s anti-heroic laughter, she inhabited a milieu where the studio smelled of glue, ink, and cigarette ash, and where salons and cafés carried a special kind of fatigue, since the Great War had trained every conversation to expect interruption.⁴ Her marriage to Jean Crotti brought an intimacy with a parallel strain of spiritualized mechanism—an attempt to grant the machine an aura—yet her own work retained a sharper domestic intelligence, as if she watched the grand gestures of avant-garde men and kept a smaller, more precise score for how history lodges in the body.⁵

Ariette d’oubli de la chapelle étourdie (little aria of forgetting of the dizzy chapel) arrives in 1920, when Europe’s air still held the aftertaste of trenches and influenza, and when Paris, eager for dancing and speed, also carried an undertow of bereavement that required disguise.⁶ In such an ether, memory became an unstable currency: too much remembrance and the nerves seized; too little and the dead turned into decor. The title stages that instability as music, since an ariette belongs to breath and phrasing, and as architecture, since a chapel implies ritual enclosure, yet the adjective étourdie gestures toward vertigo, intoxication, dizziness under shifting pressures. In this painting, forgetting behaves as a song composed for a sacred space whose equilibrium has altered, and the altered equilibrium, once perceived, starts to look physical, meteorological, measurable.