The first bamboo bow that entered my life never breathed Indian heat; it lived inside a grainy photograph pinned above my crowded desk in Portlaoise, between a postcard of Velázquez and a stained reading timetable. The photograph came from an ethnographic book on Banaras akhāṛās that a weary librarian had hunted through the catalogue, and it showed a courtyard enclosed by walls stained with time. Marigold stems lay abandoned near a shrine. A metal tray held the lamp that a priest had just quenched in a brass bowl. On the grey concrete someone had drawn a charcoal ring, and in the shadowed corner a bow leaned with its grip wrapped in frayed red cloth, three blunt-headed arrows resting in a clay pot beside incense ash and a single peacock feather. A boy, with bare feet and thin arms and a kind of unwieldy attention in his posture, faced the target with his back to the camera, while an older man with wrestler’s shoulders and cloud-white hair guided the stance with one heavy hand. The caption merely quoted a line from Mundaka Upaniṣad about Om as bow and the soul as arrow, the Absolute as target,¹ yet the frozen scene already moved, as photographs sometimes move when the observer’s hunger supplies time and sound: a scooter in the lane and a bell in the shrine; somewhere in the composite silence, the tiny twang of a bowstring that my ears never heard yet my reading had prepared.

I sat far from Ganges water, under Irish rain pressed against window glass, and I read the caption again while my eyes ran from the photograph to the Sanskrit on my desk. A cheap edition of the Upaniṣads lay open, the Devanāgarī script thick as brambles, while Gambhirananda’s English prose tried to carry into my language a sentence that Indian children treat almost as proverb: Om as bow, individual self as arrow, Brahman as mark.² The thought formed slowly, with resistance, that here a civilisation had taken a weapon and turned it upright in imagination, so the line of flight rose from ground toward sky, from ego toward a presence that receives names like Brahman or Śiva and speaks from within the heart. Dhanurveda, which my sources presented as an upaveda aligned to the Yajurveda, spoke of posture and grip, of stringing and judging distance, and of rules of combat that forbid striking the fleeing or overwhelming the weakened with numbers, yet my gaze kept drifting back to that photograph in which stance and devotion flowed together along a single curve of wood.³ An arrow released in such a courtyard began to appear as something double: it travelled outward through air toward a rough circle of charcoal and inward through conscience toward an invisible listener.

At that stage my body knew archery only through Western echoes: illuminations from medieval psalters with crossbowmen squeezed between saints, descriptions of English yew bows under skies the colour of lead, the occasional tourist demonstration in a European castle where children shot at straw while bored staff corrected their elbows. Academic training had pressed Plato and Augustine into my bones; Indian texts waited at the threshold like guests whose language I barely understood. In that earlier mental world, arrows mainly served royal will or some stern concept of law, or else punctured bodies on behalf of revolutions that preferred bullets. When I opened the Bhagavadgītā with serious intent for the first time, in a Dublin café where cups clinked against saucers and damp coats steamed under yellow light, I expected pious embroidery around a familiar warrior. Instead I met Arjuna in collapse.

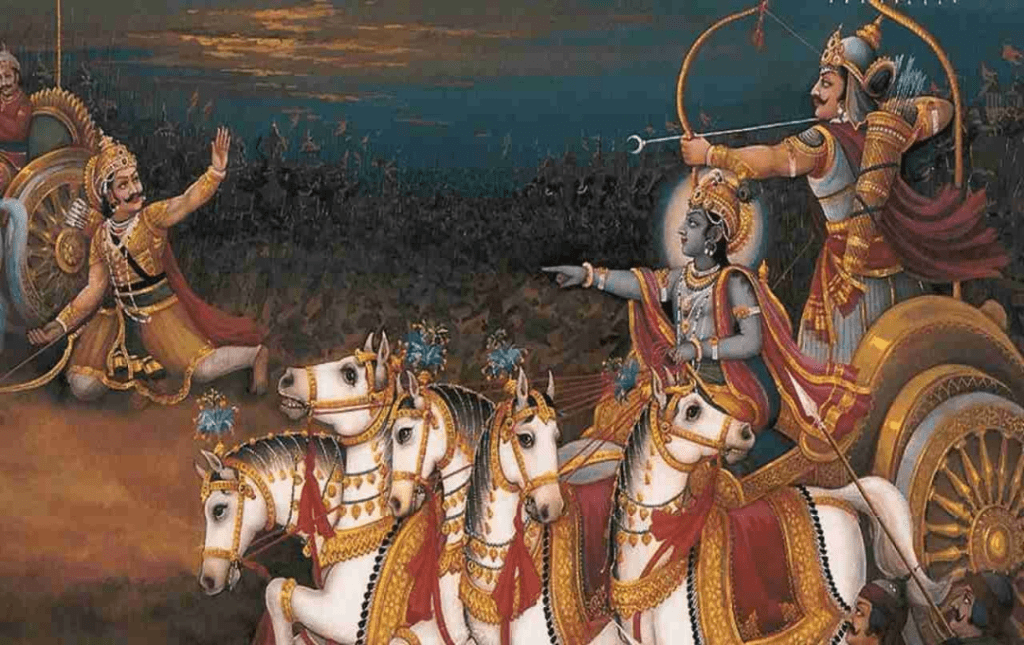

Arjuna’s breakdown arrived as print, yet the scene stepped quickly beyond the page. He stands between two armies while conch shells cry out and chariot wheels grind against the earth. He sees cousins, teachers, and friends placed across from him, ready to fall under his own hand, and his great bow, Gāṇḍīva, slips from his grip.⁴ The commentary beside the Sanskrit spoke of “the yoga of despondency,” and I felt with an uncomfortable intimacy that the first move in this archery lay not in prowess but in paralysis. Muscles fail, the jaw begins to shake, purpose runs thin, and the warrior’s arm turns away from long habit. Sri Aurobindo, whom I had approached gingerly since the word “ashram” awakens every European suspicion I carry, read that moment as spiritual autobiography: Arjuna becomes emblem of the modern conscience that discovers the immense weight of action and recoils from its own capacity for harm.⁵ The warrior’s refusal to draw seemed to mirror my hesitations before texts whose gravity I sensed while I still lived outside their world.

In the Gītā, Kṛṣṇa answers Arjuna with sentences that Indian schoolchildren repeat from memory and Western philosophers prefer to paraphrase. Kṛṣṇa grants neither sentimental comfort nor escape from the field. Bodies will fall; grief waits behind every victory; the tightness in the chest persists. What he alters concerns the direction and ownership of the shot. Action belongs to the archer only in the limited sense in which plough and ox belong to the farmer, since a deeper proprietor seated in each heart turns the axle of events. The archer participates in a wider choreography when he acts without clinging to the reward, and he hands over success and failure together at the instant of release. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, whose translation grew dog-eared and soft on my desk, described this condition as a life of detached dynamism, where the world retains brightness and urgency while the ego gradually releases its grasp on outcomes.⁶ Under his guidance I began to read the archery passages less as epic ornament and more as instruction: the bowstring receives full tension, the arrow flies with unshaken intensity, yet the result passes immediately into another jurisdiction, so labour gains an unexpected lightness, free from the bookkeeping of resentment.

As my study widened, Śaṅkara’s Advaita Vedānta entered the room with its own stern clarity. I first met his commentary on Mundaka in a small volume whose glue began to give way before I reached the last pages. For Śaṅkara, the individual archer misunderstands the entire situation as long as he imagines a genuine distance between bowman and mark. The ātman that draws the string already keeps its inner continuity with Brahman; the shining target always stands within the one who aims. When Mundaka declares that one must shoot with undivided vigilance and through that vigilance become one with the mark, the Advaitin hears an unveiling of unity that merely stages separation as sacred drama.⁷ In my notebook I sketched first a bow and a separate disc, then a second drawing where bow and mark overlapped until they formed a single circular figure. A line in the commentary suggested that the arrow’s apparent flight simply narrates the mind’s recognition of a truth that preceded every gesture—a claim that both tempts and frightens a Western reader brought up to guard individuality as the last fortress.

Around the same months, I returned to Jiddu Krishnamurti, whose talks I had once approached with youthful excitement and then with fatigue. Under the pressure of this archery question his suspicion toward systematic paths gained a sharper edge. He entered my study through grey recordings and slender volumes from Dublin charity shops, his speech measured, his silences longer than many writers’ arguments, his politeness edged with refusal. Krishnamurti would accept the bow as image for awareness only under severe conditions; he turns away from gurus, from inherited methods, from promises of gradual ascent. For him, attention unfurls in an instant free from reward-seeking, tradition, or programmes of self-improvement. The only arrow that deserves respect travels through the undergrowth of habit and fear inside the mind, cutting without reliance on rule-books, since every rule hardens quickly into fresh bondage.⁸ In my margins I wrote: “Śaṅkara: the arrow reveals unity that has always held. Krishnamurti: the arrow destroys every trusted map.” Between them archery acquired a double life, at times a sacramental rite guided by scripture, at times a solitary seeing that tears up every script.

While those voices argued across my shelves, another figure entered: Abhinavagupta, the Kashmiri Śaiva who treated the cosmos as theatre of consciousness. I met him through Dyczkowski’s translation, bought second-hand from a scholar in Limerick who admitted in his email that he felt exhausted by the density of the Tantrāloka. Abhinavagupta writes as if every act of perception carries an arrow: awareness shoots outward from universal consciousness toward each finite object, and in that same movement Śiva recognises Himself.⁹ The archer’s shaft becomes emblem of Spanda, vibration, the pulse through which the Absolute savours its own multiplicity. On a damp Irish afternoon, with the Slieve Bloom Mountains hidden behind a sheet of rain, I tried to imagine an anonymous schoolboy in Haryana: compound bow in hand, standing on a dusty field behind classrooms built in concrete. Ethnographies and clips described dhanurāsana stances derived from old descriptions in the Agni Purāṇa, straw targets propped against walls, inexpensive quivers, coaches who checked their phones between ends.¹⁰ Yet through that haze of modern life I could glimpse the moment that every archer mentions in one form or another. Breath deepens; the field grows quiet; the air near the bull’s-eye seems to contract and brighten; the arrow leaves the string; for that heartbeat the shot feels utterly personal in its effort and strangely impersonal in its clarity, as if another awareness sees through the eye and breathes through the lungs. Abhinavagupta gives that fugitive intensity a metaphysical name.

Dhanurveda itself reached me through patchwork: English paraphrases of Agni Purāṇa passages, scholarly reconstructions by Johnson and others, stray references inside studies of South Indian martial arts.¹¹ These sources describe types of bow and arrow and the bodily stances that support them, and they include prescriptions for chariot warfare, all wrapped inside an ethical and ritual frame. The text enters lists of upavedas beside Āyurveda, Gāndharvaveda, and Sthāpatyaveda; each discipline heals a different dimension of existence—body, song, dwelling, or kingdom. Under that light, archery appeared less as technique and more as a medicine directed toward the body politic and the injured psyche of the warrior. South Indian manuals, preserved through Nair and Kalarippayattu lineages, praise the archer who trains in the teacher’s presence, so that skill, humility, and responsibility grow together.¹² When I read those lines at my kitchen table, with the smell of boiled potatoes lifting from the pot and my son’s schoolbooks piled near the salt, I felt a quiet envy. My own academic shooting, expressed through articles and drafts, seldom unfolded under the steady gaze of a single master, yet the demand for accountability persisted, since each argument aims at some unknown reader’s heart.

The twentieth century layered further complexity over the bow. Gandhi entered my reading not as framed icon but through the heavy grey volumes of his Collected Works, where letters and speeches, along with quick marginal notes, reveal a man who leans instinctively toward metaphor. Again and again he described satyāgraha as an arrow of truth, straightened through discipline and sharpened through sacrifice.¹³ He turned away from physical weapons, yet his language kept the grammar of the bow: aim, penetration, wound, and a patient kind of healing. Across the same historical floor walked revolutionaries who embraced bombs and pistols and sometimes still kept bows. Their pamphlets and songs drew strength from Arjuna’s obedience to Kṛṣṇa on the field of Kurukṣetra and read the Gītā as summons to armed resistance. Modern Indian politics, seen through this lens, begins to resemble a hall where many archers share a single armoury. Some quivers hold only symbolic arrows; others insist that heavy oppression yields only before steel; each party claims loyalty to the same scriptural warrior. My reading, carried out in the uneasy comfort of Irish democracy, never granted me authority to judge between them. I could only notice how archery metaphors gathered the entire quarrel between violence and non-violence into the shape of one tense bow.

While pursuing this research, I first encountered the phrase “the creed of the Aryan fighter” in Aurobindo’s prose at a wooden desk in the National Library of Ireland, that echoing rotunda where pages whisper and footsteps circle the dome. The sentence rose from a foxed volume that reached me only after several failed call slips and a quiet apology from the librarian, who glanced at the term “Aryan” on my request form with a slight tightening around the eyes, as if the building itself remembered other histories attached to that word. The catalogue had buried Aurobindo among “Oriental religions,” a label heavy with dust from another century, so when the book finally arrived—thin paper with a brittle spine and the faint scent of Pondicherry ink—I felt an odd mixture of gratitude and unease. Aurobindo sketched an ideal warrior whose courage, compassion, and obedience to dharma grow together, whose arrows serve sacrifice instead of vengeance, whose power remains bounded by reverence.¹⁴ I copied the passage into my notebook, slowing each time my pen crossed the word “Aryan,” since European memory around those letters holds scars that rarely fade. A short walk later, Kildare Street bus shelters shouted at me to hit targets and aim higher, to strike while some commercial iron glowed. These slogans dragged archery into the service of sales, borrowing the bow’s clean outline while emptying away any cosmic or ethical theatre, so the tightened string served only quarterly gains. Back at my desk in Portlaoise, with a cheap kettle sighing in the corner and a grey sky pressed low over the estate roofs, I tried to restore a measure of weight inside my own sentences: every aim shapes the archer; every chosen target reveals a view of the human. When a reproduction of Arjuna kneeling beside his fallen bow lay across my notes, silence grew between bookshelf and window, as if that painted warrior shared a posture with the office worker hunched over spreadsheets, both of them suddenly uncertain about the script of achievement that had guided their arms. Email exchanges with colleagues pushed the matter further. One warned that the phrase “Aryan fighter” would confuse or wound European audiences. Another, an Indian historian on a visiting fellowship, wrote a patient reply explaining how Aurobindo’s expression had entered discussions of courage and self-rule without loyalty to race doctrines developed on my side of the world. Those conversations nudged me toward a different kind of archery, where each citation becomes a shot between cultures and each footnote tests whether my hand has aimed with enough care.

Email threads and conference corridors eventually brought living interlocutors from India into this solitary project. An engineer from Pune, who had competed in state-level archery as a student, wrote after a mutual acquaintance forwarded him a rough chapter. His first message arrived at 3:17 a.m. Irish time, full of technical detail about draw weights and let-off percentages and the small adjustments needed to keep sight marks steady when monsoon air grows heavy. He attached a blurred photograph of a field behind his old school: a row of straw butts, a sagging safety net, a boundary wall painted with Hanumān in orange and white, the monkey-god’s raised mace presiding over the whole line of targets. Later messages described a coach who loved to quote Sanskrit lines about practice as offering, about the obligation to appear on time and string the bow in the teacher’s presence so that skill and accountability grow together. Our first phone conversation suffered from lag and static; his voice thinned whenever meaning grew important, so fragments reached me like arrows through fog: karma, effort, Kṛṣṇa’s counsel on fruits of action, the need to greet wild flyers and tight groups with the same composure. During one call he spoke about a crucial competition where, after several poor shots, he finally accepted that some arrows would stray. At that instant, he said, a peculiar lightness entered his shoulders, and the next end flowed without tremor. I stood in my kitchen with the mobile pressed to my ear and the kettle cooling behind me, scribbling half-heard phrases on the back of a supermarket receipt while his account carried Radhakrishnan’s abstractions and Aurobindo’s sentences out of the reading room and into a world of dust, sweat, and peepal shade. Later that week, seated again in the National Library, I opened my notebook and found his words crammed between lines of Sanskrit—a cramped dialogue stretching across continents. The page smelled faintly of coffee and old bindings. Outside, Dublin buses continued to shout about targets and success. Inside, a single sentence from Pune—“some arrows will stray and that freedom improves the shot”—stood beside a verse where Kṛṣṇa urges Arjuna to act and relinquish fruits, and for once the relation between field and text felt less like theory and more like an arrow returning to the place it had always meant to land.

I began this work as a Western academic anxious to expand a private canon, yet slowly the gestures of Indian archery entered the muscles of my thinking. Mundaka’s bow and Śaṅkara’s unity, Krishnamurti’s refusal of method conversing with Abhinavagupta’s vibration, Gandhi’s truth-arrow and Aurobindo’s fighter, finally the engineer’s compound bow in Pune: these figures gathered around one metaphorical weapon and turned it in their different hands. Through them a pattern emerged. An arrow always expresses a decision. In many European stories, that decision concerns a ruler’s will or a strategic calculation or a solitary protest pitched against fate. Inside these Indian sources, the decision acquires another dimension: the relation between a finite agent and an immeasurable order. Each shot carries questions: who owns this arm, who authorises this motion, who receives the final effect?¹⁵ When Arjuna hesitates, when Kṛṣṇa speaks, when Śaṅkara comments, when Krishnamurti tears up paths, when Gandhi fasts, when a boy in Haryana sends his first tight group into the gold at thirty metres, that cluster of questions travels along the string from hand to hand.

On evenings when Irish light lingers and deadlines fall quiet for an hour, I sometimes stand in the narrow strip of garden behind the house with a beginner’s recurve that arrived one day in a cardboard box. The purchase grew out of impatience with purely textual archery. No Banaras courtyard, no Ganges, no priest; only a battered straw bale set against a wall, a neighbour’s cat watching with faint disdain, the smell of turf smoke sliding across the estate. I brace the bow, feel resistance grow as the limbs curve, and every phrase I have read returns at once: Om as bow, self as arrow, some unnamed mark that outlives both success and failure. My shoulders protest; my release lacks polish; arrows wander; the target carries the record of awkward attempts. Yet in the rare second when breath, sight, and motion consent to one another and the arrow leaves my fingers and settles close to the centre, I begin to understand why India placed so much theology, philosophy, and politics upon this simple device. Each such second demands gratitude and a certain fear, since every aim, even in a small Irish garden, writes a line into the archer’s own soul.¹⁶

Notes:

1 The photograph described here derives from an ethnographic study of Banaras akhāṛās in which courtyard archery appears beside wrestling and devotional ritual; the caption cites Mundaka Upaniṣad 2.2.4 on Om as bow and the self as arrow. For the Sanskrit passage and Śaṅkara’s commentary, see Mundaka Upanishad with the Commentary of Śaṅkarācārya, trans. Swami Gambhirananda, Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata, 1958, pp. 110–113.

2 The metaphor of Om as bow, ātman as arrow, and Brahman as mark functions here as a liturgical and philosophical condensation of the Upaniṣadic drive toward identity between self and Absolute. Julius J. Lipner notes that such dense images anchor Hindu teaching in memorable narrative and ritual forms; see Julius J. Lipner, Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Routledge, London, 1994, pp. 86–92.

3 Dhanurveda appears in classical lists of upavedas attached to Yajurveda and survives in fragments within Purāṇic compilations such as the Agni Purāṇa. These passages discuss weapon types, stances, and combat rules while assuming an ethical and ritual frame. See W. J. Johnson, Dhanurveda: The Science of Archery, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009, pp. 3–27; and The Agni Purāṇa, vol. 2, trans. J. L. Shastri, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1995, chap. 249, pp. 1012–1019.

4 The portrayal of Arjuna’s physical collapse in the opening chapter of the Bhagavadgītā—his limbs weakening, mouth drying, bow slipping from his hand—creates what Angelika Malinar calls a “ritual moment of crisis,” in which heroic identity yields to existential questioning. See Angelika Malinar, The Bhagavadgītā: Doctrines and Contexts, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, pp. 61–82.

5 Sri Aurobindo treats Arjuna as “the representative man,” a type who carries within himself the divided will of humanity under the pressure of divine demand. His Essays on the Gita read the battlefield dialogue as both historical and symbolic drama, in which the warrior’s hesitation serves as threshold to a higher understanding of action. See Sri Aurobindo, Essays on the Gita, vol. 1, Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry, 1922, pp. 31–52.

6 Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan’s translation and commentary on the Bhagavadgītā frame Kṛṣṇa’s teaching on “desireless action” as an answer to the ethical tension between engagement and renunciation. He presents the ideal as a “detached dynamism” in which the agent works intensely while surrendering attachment to fruits. See S. Radhakrishnan, The Bhagavadgita: With an Introductory Essay, Sanskrit Text, English Translation and Notes, HarperCollins, New Delhi, 1993, pp. 161–189.

7 Śaṅkara’s Advaitin reading of Mundaka 2.2.4 treats the act of shooting as an allegory of realisation: through knowledge (vidyā) and meditation (dhyāna), the apparent arrow of the individual self dissolves into the mark which always belonged to it. Patrick Olivelle’s translation emphasises the language of vigilance and single-pointed absorption; see Patrick Olivelle, Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996, pp. 279–283.

8 Jiddu Krishnamurti’s teaching rejects formal methods, gurus, and gradual paths, insisting on direct perception free from authority. His use of images often plays against traditional readings: weapons and paths signify danger rather than security. For a compact expression of his approach to awareness and conditioning, see J. Krishnamurti, Freedom from the Known, Victor Gollancz, London, 1969, pp. 57–73.

9 Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka and related writings articulate the doctrine of Spanda, the “vibration” or dynamic throb of consciousness through which Śiva manifests and recognises the universe. The arrow offers a convenient image for this outward surge and return. A lucid introduction appears in Mark S. G. Dyczkowski, The Doctrine of Vibration: An Analysis of the Doctrines and Practices of Kashmir Shaivism, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1987, pp. 157–182.

10 The Dhanurveda sections of the Agni Purāṇa list several standing postures whose names recur later in yogic āsana catalogues, including dhanurāsana. Gudrun Bühnemann traces this crossover, arguing that martial and yogic disciplines share a common repertoire of bodily forms and Sanskrit terminology. See Gudrun Bühnemann, Eighty-Four Āsanas in Yoga: A Survey of Traditions, DK Printworld, New Delhi, 2007, pp. 54–61.

11 English-language engagement with Dhanurveda remains fragmentary, since the classical text survives only in partial form. Johnson’s monograph and scattered articles draw on Sanskrit and Purāṇic materials; South Indian practice traditions also preserve archery lore. See Johnson, Dhanurveda, pp. 3–59; and the contextual remarks in Niels Gutschow, Benares: The Sacred Landscape of Varanasi, Orient Blackswan, Hyderabad, 2006, pp. 241–263.

12 Phillip B. Zarrilli’s study of South Indian martial arts shows how teachers link technical precision with ethical and therapeutic concerns. Although his focus lies on kalarippayattu and related forms, his discussion of “practice in front of the teacher” and the concept of marmmam (vital spots) reveals continuities with Dhanurveda ideals of responsibility and restraint. See Phillip B. Zarrilli, “To Heal and/or To Harm: The Vital Spots (Marmmam/Varmam) in Two South Indian Martial Traditions,” Journal of Asian Martial Arts, vol. 1, 1992, pp. 1–24.

13 Gandhi’s language of satyāgraha as a sharply directed force appears throughout his correspondence and speeches. While he renounces weapons, he frequently uses cutting and piercing metaphors for truth and non-violent resistance. For examples, see The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. 31, Publications Division, Government of India, New Delhi, 1968, especially letters from 1919–1920.

14 In essays such as “The Creed of the Aryan Fighter,” Aurobindo presents a warrior ideal marked by fearlessness, obedience to moral law, and refusal of cruelty. Violence receives strict spiritual conditions, and courage binds itself to compassion. See Sri Aurobindo, Essays on the Gita, vol. 2, Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry, 1922, pp. 3–19.

15 The question of agency in the Bhagavadgītā—whether the individual truly acts or merely participates in divine activity—has generated extensive scholarship. For an accessible survey of interpretations, including classical commentators and modern thinkers, see Malinar, The Bhagavadgītā, pp. 199–236; and Lipner, Hindus, pp. 210–223.

16 For an attempt to read archery as a meeting point between Eastern and Western philosophies of action, with particular emphasis on Gītā, Plato, and Kierkegaard, see Martin Smallridge, An Arrow Knows no Master: Thirteen Lectures Framing Archery Axioms in Western Philosophy, TIFAM CLG Publishing, Portlaoise, 2025, Lecture I, “Between Bow and Being,” and Lecture IX, “The Leap into the Void.”

Views: 1

This article is part of our free content space, where everyone can find something worth reading. If it resonates with you and you’d like to support us, please consider purchasing an online membership.