“

There is no fault nor detriment / in facing bare the cruelty of world…” — We’ll Go Asleep

Imagine, now, not just a tool or a sport, but a whisper that’s survived since we first dared to shape the world with our hands: archery. It doesn’t shout its purpose. It waits. And in the waiting, teaches. Think of the bow, not as invention, but inheritance—curved wood and sinew remembering things we’ve long tried to forget. There’s an honesty in it. A promise wrapped in tension. The promise that if you breathe right, steady your heart, and let go with grace, something true will fly from you.

You see, it’s not really the arrow we’re chasing. It’s the silence after.

The art of archery is older than history and younger than every person who’s ever drawn a bowstring in the hush before dawn. Born in bone, flint, and fire, it once meant food, survival, protection. But then—as with all things we survive—it became more. A discipline. A mirror. A way of listening to the self by aiming beyond it. In every age, it has changed its clothes—from war-draped leather to monkish robes to synthetic suits—but it’s never abandoned its soul: the quiet challenge between intent and act.

What draws us in isn’t the thud of impact or the score. It’s the breath taken before. That drawn moment where you stand alone with the question: are you ready to let go? There’s a holiness in it, like mass said under trees or psalms whispered across frostbit mornings. A pause pregnant with possibility.

The archer doesn’t just contend with distance. They contend with themselves. Every shot a summoning, every miss a reckoning. And isn’t that the whole of human striving? To align the inner motion with the outer arc? It’s not just physics—it’s faith. A kind of prayer that doesn’t ask for result, only clarity of effort. In this way, archery becomes a conversation: between hand and eye, will and world, self and silence.

Look east and you’ll see how others knew this truth long before we dared to name it. In Japan, Kyudo turns the archer’s stance into ritual, the shot into pilgrimage. The bow isn’t a weapon—it’s a guide. To miss the target with perfect form is not failure; it’s testament. A declaration that the journey inward matters more than the mark struck.

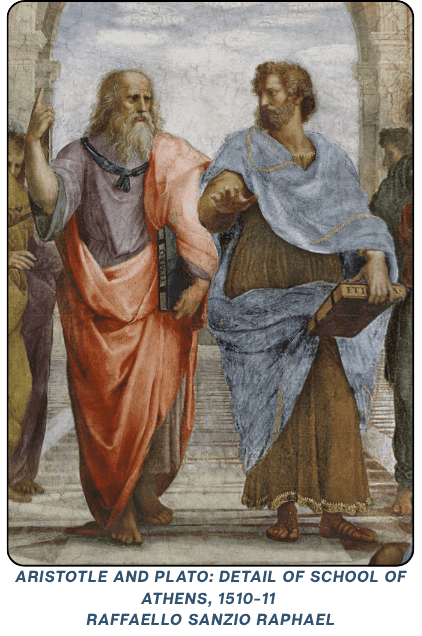

And in ancient Greece, where Plato and Aristotle stitched philosophy into every fibre of life, archery fit easily among the virtues. Plato might have seen the archer as a metaphor for the soul aiming beyond shadow toward the form of good. Aristotle, more grounded, might have admired the practical balance of it all—the telos of the arrow, the phronesis in the archer’s poise, the golden mean struck not in hitting but in the grace of release.

Is this not what we strive for? In writing, in living, in love? That blend of discipline and drift, precision and surrender? The bow teaches what few things do: to hold tension without breaking, to act without forcing. To aim not for perfection, but for presence.

Across centuries and cultures, archery has served as symbol and story—used by mythic heroes, divine agents, and quiet hunters. But today, stripped of ceremony, it still has power. Not because it kills, but because it clarifies. It’s a way to re-enter the body, to feel the wind again, to measure time in heartbeats, not schedules.

In a world that hurries us toward outcome, the bow says: wait. Breathe. Attend. Not to the noise outside but the hush within.

And perhaps that’s what keeps it alive—not just tradition or sport, but the hunger for something real. A discipline not of winning, but of remembering. Not domination, but return. And in this way, the archer’s path remains open to all who seek to walk it—not as heroes, but as humans. Faltering. Aiming. Letting go.

What lingers, after the shot has flown and silence falls again, is not triumph or regret. It is the echo of having tried with your whole self. And that—quiet as it is—is no small thing.

Perhaps, in the end, the arrow never mattered at all. Perhaps it was always about the draw.

So, come along with me, won’t you? Let’s take the road where thought meets touch—where the dreams of old philosophers still hang like mist on a wet morning. There’s something in Plato’s gaze, stretched far beyond the bend of the world, that still finds us when we stand alone with a bow in hand. And Aristotle, sure, he’s the fella with his feet in the dirt, pointing to the shape of the land, saying, “Start here, and we’ll find the way.”

What I’ve found, standing in fields with nothing but silence and the soft breath of wind, is this: the arrow teaches you things no book ever dared. The perfect shot isn’t in the hitting—it’s in the trying. It’s in the stillness just before the string hums. That moment, fleeting as a trout’s flick in shadow, is where a bit of your soul slips out and says, “I’m here. I’m trying.”

Plato’d call it a Form—capital F. The real thing behind the thing. But you don’t need ancient Greek to know the feeling. We’ve all stood there, eyes fixed on a point that’s never quite within reach. The ideal’s out yonder, always a step ahead. You aim not because you think you’ll strike it clean, but because in aiming, you become something sharper, steadier, more true.

And that’s the work, isn’t it? Not the hitting, but the aligning. Not winning, but becoming.

The lad down the road—Seamus, old carpenter’s son—he once told me that learning to saw straight taught him more about truth than church ever did. Same with archery. You can’t lie to the string. It won’t listen. It shows you as you are, every twitch and tremble. But it also gives you grace. You draw again. You breathe. You get better by being broken, slow and honest.

Aristotle might’ve nodded at that. He loved a good habit. Not in the dull sense, mind you, but as a shape you build into yourself, like muscle from stonework. He’d say virtue is the mark you leave on your own spirit through choice, through steady hands. And sure, what is shooting if not that? Not just the act, but the echo it leaves inside you. A kind of quiet honour. A way of facing things.

The world these days moves too fast to catch much meaning. Everything’s measured, timed, and posted. But archery’s old. It belongs to a slower beat. You don’t rush a shot worth taking. You listen. You watch the trees, the hush between birdsong. You let your breath teach your body the way. And sometimes, just sometimes, everything lines up, and the shot sings.

That song—it’s never the same. But it’s always yours.

There’s beauty in that, and ache too. Because it slips away. You can’t hold it long. Like the perfect sunrise, or the scent of your mother’s coat when she hugged you tight on winter mornings. These things live in moments. You don’t own them. You meet them.

And isn’t that the essence of being human? This longing, this reaching for something just beyond? We are creatures of almost. And yet, in every draw of the bow, in every trembling hand and breath held too long, we tell the world, “I’m still reaching.”

That’s courage, I think. Not charging into battle, not boasting in bars—but standing in a field with your fears, your flaws, and still trying to aim straight.

We come from a long line of folk who knew that. Warriors, yes, but also poets, monks, shepherds. People who knew how to carry silence without shame. Who sang not to be heard, but to remember. And when we draw the bow now, it’s their voices that guide us, even if we don’t hear them clear.

The Greeks had their Forms. We’ve our ghosts.

And yet, the lesson’s much the same: Aim true. Accept the miss. Learn the weight of your own hands.

That’s where the real journey lies—not in the hitting, but in the drawing. Not in the finish, but in the going. And if along the way you find a glimpse of grace, well then, you’ve found something worth keeping.

Even if the arrow doesn’t land.

Plato, for all his lofty ways, understood something the body knows before the mind can name it. He spoke of good sport—not as a test against others, but as a kind of music made between the soul and the limbs. He pictured its highest form not in victory or spectacle, but in the quiet perfection of a movement well made. A moment where mind and muscle stop wrestling and start dancing, each guiding the other without pride or panic.

That’s where the archer lives, isn’t it? Not always in the win, but in the trying. The long, slow pull toward something finer than flesh alone can manage. You’re not just loosing arrows—you’re chasing the shape of the thing itself, the pure act, the clean draw, the true release. You’re aiming for something that lives in the bones of the world, even if you’ve only caught the whisper of it.

The Ideal Shot isn’t just a well-placed arrow. It’s a kind of prayer. A way of touching something older than time. If Plato was right—and who’s to say he wasn’t—that shot reflects the highest kind of Good. The kind that casts light on all the rest. And when an archer works toward that—steadily, stubbornly—they’re not just practicing. They’re reaching, heart and hand alike, for something sacred.

It’s not about the bullseye. It’s about meaning. About finding your place in a rhythm that began long before you were born.

That path, though—it’s not a smooth one. You’ll remember Plato’s cave, maybe. He spoke of people chained in the dark, staring at shadows cast by firelight, mistaking flickers for truth. But then one breaks loose, stumbles upward, eyes aching in the sun. He learns what the world really is—not shadows, but things. Not guesses, but knowing.

Every archer’s been there. Early on, or deep into it, you find yourself stuck. You’re doing the same thing over and over, expecting it to land different. You chase gadgets. You mimic someone else’s form. You score a lucky shot and think you’ve cracked it. But it slips. The next dozen go wide, and the doubt comes in like tidewater.

That’s the cave. And the shadows are all the things you’ve been told, all the shortcuts, the half-learned habits. A crooked stance that feels natural because it’s familiar. A rushed release you’ve taught your muscles to love. Coaches who mean well but offer only fragments. Thoughts in your own head that tell you you’re not built for this.

They’re not lies exactly—just partial truths that have gone to seed.

The hardest part, then, is turning. Seeing those flaws and facing them straight. Not with shame, but with a kind of hungry curiosity. Why does the shot wobble? Where does the tension break? What have I leaned on that doesn’t hold?

That first moment of clarity—when you stop blaming the bow, or the breeze, and start listening to your own body like a thing worth hearing—that’s the fire behind you, flickering off the chains.

From there, it’s study. Real study. Not bookish, but bodily. Learning where the weight belongs in your heel. How to hold breath without holding fear. Discovering that draw cycles aren’t just technical—they’re personal. That your anchor point is less a place than a promise: this is where I meet myself before I let go.

It’s slow work, and sore. You’ll lose shots before you gain them. You’ll curse old muscle memory as it fights back. You’ll feel awkward in your own skin. That’s part of it. That’s the climb.

And sometimes you’ll need a guide—someone who’s seen their own cave, who won’t fill your head with fluff or sell you shiny fixes. They’ll just stand beside you, point to the shadows, and help you walk beyond them.

But if you stay the course—if you trust the craft to teach you—you come out changed.

The target stays the same, sure. But the aiming becomes different. Calmer. Cleaner. Not from control, but from understanding. You shoot now from a place that knows, not a place that hopes.

And you begin to see the bow, and your body, and your thoughts, not as separate things, but one movement. One breath. One line.

That’s the sun. That’s the world made clear. Where every arrow becomes an act of awareness, and the archer isn’t chasing perfection—they’re living it, one shot at a time. Mistakes still come, aye. But they don’t shake you. You’ve met yourself already. You’ve seen the dark. You’ve come through.

And now you shoot not just with muscle or mind, but with a kind of quiet knowing.

You’ve become what you were after.

The archer’s climb from the cave isn’t just a matter of loosening the knots in their form or standing steadier in the wind. There’s a second liberation at play—a quieter one. A loosening from the inside out.

You learn, somewhere along the line, that not all mistakes live in the hands. Some take root behind the ribs, in the quiet doubts you whisper when you think no one hears. The shadows we carry aren’t always visible. They’re old beliefs that whisper through the muscle—“You’ll never land that shot,” “You’re built wrong,” “That wasn’t luck, it was a fluke.” You could have the cleanest technique this side of Galway and still be thrown by a flicker of fear that lives behind the eyes.

That’s the other cave. The one inside.

And to come through it—to walk into the light with your head high and your breath steady—is the harder task by far. It asks for more than skill. It calls for a kind of balance inside yourself, a steady flame you’ve got to tend in the quiet hours, when there’s no crowd, no scorecard, just the sound of your own thoughts and the twang of string in the wind.

When you do emerge—when form meets clarity, and effort aligns with insight—you begin to see that accuracy isn’t a trick or a gift. It’s a sign. A sign that you’ve done the work, both in the body and in the soul. And from there, the bow stops being a tool. It becomes a teacher.

That’s when archery turns from pastime to path. From practice to pilgrimage.

And Plato, strange old thinker that he was, has a fine way of describing what happens inside a person on that kind of journey. He spoke of the soul as a creature made of three parts—each pulling in its own direction. There’s the head, where reason lives, always chasing what’s true and lasting. There’s the chest, where spirit stirs—pride, courage, the hunger for honour. And down low, in the belly, sits appetite, always reaching for food, warmth, comfort, delight.

Now, these three don’t always agree. And that’s where the struggle lies.

He paints it better still in the tale of the chariot—do you remember it? A charioteer steering two horses, each with a mind of its own. One horse is bright-eyed, strong in discipline, eager to rise. The other is wild, snorting at every distraction, straining for pleasure over purpose. And the driver—reason—is meant to hold the reins tight, guiding the pair not toward any hill or market, but upwards, toward truth.

It’s not a clean ride. Never was. But when the driver holds steady, when the noble horse lends its might and the wild one yields, then the soul flies. Then it climbs toward a goodness that’s more than personal reward—it’s shared, it’s felt, like a story passed round the fire that leaves the air warmer than it found it.

The archer’s soul—if we can use such a word without sounding grand—works the same way.

The mind might know what to do, the body might remember the shape, but unless the heart’s in tune, unless the appetites are quiet and the will is strong, the arrow won’t fly clean. You’ll feel it in the hand. The tremble. The hesitation. The way you grip the string too tight or flinch in the breath before release.

To shoot well is to ride well.

And that’s the test, isn’t it? You could know every inch of the form and still miss if your inner reins are slack. You could shoot straight one day and scatter the next, not because your body’s forgotten, but because your spirit’s in rebellion, or your appetites have taken the lead.

But when all three move together—when the wild horse is steadied, when the noble one surges forward, when the charioteer sits tall and true—then the shot flies as if guided by something more than muscle. It moves like memory, like intention, like a kind of grace made solid.

That’s the real work of the archer. Not to conquer the target, but to learn the shape of their own soul. To know when it falters, and how to steer it back. And in that, there’s a kind of justice. A kind of joy.

Because each shot becomes a step on a longer road. And every release is a letting go—not just of the arrow, but of doubt, of fear, of the small self that clings too tight.

And isn’t that something worth chasing?

You see, the soul of an archer doesn’t sit tidy in the shoulders or rest easy in the limbs. It stretches deeper than that—past sinew, past breath. And if you listen close, you’ll hear it wrestling inside.

Plato had a sharp eye for the old struggle, and for all his ancient Greek sandals, he understood something universal. He saw the soul as a team of three, yoked together in one body, each with its own pull. One part watches the stars, one charges toward glory, and the last—well, it wants food, sleep, comfort, the easy way when the hard road stretches long.

In an archer, all three wake early.

The part that thinks—the charioteer, if we follow Plato’s telling—keeps the logbook. It watches how the arrow drifts in a crosswind, learns the language of tendons, and charts out each step with care. This is the part that dreams the Ideal Shot, not as a fancy, but as a shape to reach for. It learns by watching, failing, asking. It plans, adjusts, and tries again with quiet resolve.

Then there’s the fire in the chest—the spirited horse. It’s the one that stands tall in a tournament, that rises when the shot matters most. This fire doesn’t ask for praise, but it does feel the pull of recognition. It wants to prove something—not just to others, but to itself. When managed well, it gives strength to the draw and courage to hold steady. But left wild, it rears. It lashes out at missed marks, flares up in pride when the arrow finds gold. It can drown reason if it gets its own head too often.

And down below, the third—the hungry one—doesn’t think much past the moment. It’s the part of you that longs for ease. That wants to skip the grind of repetition. That says, “It’s cold today, rest awhile,” or “You’ve done enough.” It’s the slouch in the stance, the glance toward distraction, the need for comfort before discipline.

Now the good archer—the archer with more than luck on their side—doesn’t silence these voices. They steer them.

They let the reason guide the reins, firm and measured. They allow the spirit to push, but never to tip the cart. And they keep the appetites in check—not banished, but given a place that won’t steer the path.

This, in its own quiet way, is justice. Not the kind carved into courtrooms, but the deeper kind, stitched into the self. Each part of the soul doing its job, none vying for rule. That harmony is what builds consistency. That’s what shapes a craft into a calling.

And here’s where Plato speaks true again. He saw sport in three shades. At its lowest, folk chase gain—money, titles, pride. The middle rung belongs to glory-seekers, hungry for applause. But the highest form of sport, he said, is something closer to art. Or prayer. Or poetry.

At that height, you’re not battling an opponent. You’re facing yourself. And not in conflict, but in communion. You draw, you anchor, you breathe. And if the arrow flies clean, it isn’t for the prize. It’s for the moment that lives just beyond perfection.

That’s the mark of the philosophical archer.

And it’s not made in one season, nor in a weekend workshop with fancy tools. It’s forged in hours spent alone with your breath and a stubborn bow. In missed shots that sting more than they should. In learning to smile at the wind. In knowing your nerves and staying anyway.

There are tools, sure. Ways to still the mind. To see fear for what it is and let it pass. To turn frustration into fuel and fatigue into rhythm. These things aren’t extras—they’re part of the training, same as grip and sight and draw length. A full regimen shapes the body, but a fuller one shapes the self.

And that’s where mastery begins.

It isn’t about perfect form in every round. It’s about becoming the sort of person who can hold that possibility without shaking. Who meets the moment with grace, even when the hands tremble. Who keeps the horses in line, and the chariot moving forward.

So the archer’s journey is not one of target after target, but step after step within the self. A kind of pilgrimage made one shot at a time.

And with each arrow sent into the wind, you offer a piece of yourself—gathered, tempered, and aimed with care.

That’s a life’s work. And a good one.

When you leave behind Plato’s high clouds and turn your gaze to Aristotle’s steadier soil, you feel a shift—not a loss, but a rooting. There’s comfort in the way he looks at things, like a craftsman holding wood in his hand, testing the grain, thinking aloud about what it might become if guided right.

He speaks of telos—the end of a thing, or maybe its soul’s hunger. Its reason for being. You don’t need Greek to get the sense of it. You know it when you feel it in your chest. A bow that draws clean, releases smooth. An arrow that holds its line like a thought well spoken. They’re doing what they’re made for. And there’s a kind of beauty in that, isn’t there?

Think of the bow. Its telos is simple: to hold energy and let it fly. The better it does that, the more itself it becomes. Same with the arrow—it’s meant to travel clean, fast, true. To carry your intent across the space between here and there. A good arrow doesn’t wobble. It doesn’t waver. It remembers the hand that loosed it and holds the line.

And now, what of the archer?

There’s more to them than grip and stance. According to Aristotle, the archer—like every person—carries a telos of their own. And it’s bigger than the range. Bigger than the score.

He called it eudaimonia. That’s not just happiness, mind you, not the smile-on-your-face kind. It’s the deep kind. The kind that roots in a life lived rightly. Not perfect, but purposeful. A life shaped by choices that build on each other like stone on stone. A life where skill becomes second nature, and virtue isn’t preached, but practiced.

In that view, the archer’s goal isn’t simply to hit the mark. That’s just the first layer. And sure, it feels good—there’s a thrill when the shaft finds centre, a soft gasp maybe, when the shot breaks silent and true. But Aristotle would say: don’t stop there. That’s a signpost, not the destination.

You’re meant to shoot well. Not once, not by chance, but again and again, through rain and ache and doubt. To draw the bow with care, to release with grace, even when the wind mocks your aim. That’s the deeper telos—your reason made action.

The Stoics echoed this later, in their rougher Roman way. Cicero said it plain: the task of the archer is to aim well. The target is beyond your control. The shot, though—that’s yours.

And isn’t that the truth? The field doesn’t promise fairness. A breeze rises. A splinter shifts your grip. You miss. But if you held your form, if you shot clean, then the miss isn’t failure. It’s just the world doing what it does. Your task remains the same: to shoot with virtue. With care. With intent.

This is where archery becomes more than sport. It becomes a way of living.

Every time you pick up the bow, you meet your telos again. Not as a burden, but as a friend. A guide. The arrow reminds you: keep steady. The string says: breathe deeper. And the target? It listens, but never speaks. That silence is part of the lesson.

Archery, then, is a technē—not just an action, but a practice. An art built on understanding. You’re not copying motions. You’re learning causes. You feel the why in your muscles. You sense it in your spine.

And the good it aims at? That too has layers.

At first, it’s the clean hit. Then, the mastered form. But in time, it becomes something richer. Shooting well becomes a mirror for being well. A practice that spills into how you speak, how you hold anger, how you carry loss. The virtues you build on the range follow you elsewhere—into your work, your waiting, your wondering.

So the archer’s telos lives in a nest of purposes. The arrow seeks the mark. The shot seeks perfection in its making. And the archer, over seasons and setbacks, seeks eudaimonia. Flourishing. A life lived in step with itself.

And that, maybe, is the true mark. Not the bullseye, but the line drawn through each act, each choice, each time you pick up the bow and say: I’m here again. I’ve come to learn.

Because archery, like living, is never finished. But it can be done well.

When Aristotle spoke of aretē, he didn’t mean perfection pressed into marble or something rare as hen’s teeth. He meant a thing doing what it was made for, and doing it well. A horse running hard and straight. An eye seeing with sharpness, full of light. A bow that bends but doesn’t break. A hand that knows its strength and doesn’t boast. That kind of excellence—it isn’t loud. It doesn’t ask for praise. It just is, steady as the sea.

And for us, for people who take up the bow, aretē becomes the shape of our daily doing. Not gifted, but grown. Not grand, but right.

Aristotle knew virtue doesn’t drop from the sky like a gift from the gods. It’s built, slow and stubborn, through practice. Through habits, formed and reformed in the thick of things. You keep choosing well, and one day you wake up with a steadier heart. That’s how he saw it. And sure, he was right.

Take patience. It’s not a thing you claim—it’s something that claims you, bit by bit, when you’ve missed the mark too many times to count and still keep showing up. When your fingers bleed from the string, but you still nock another arrow. When your form falls apart, and you build it again, brick by quiet brick.

Focus? That’s another. You learn it when you stand on the line and the world won’t shut up—wind rising, thoughts racing, someone coughing in the stands—and you find the silence anyway. You learn to aim with your whole being, to live for that second when everything else falls away but the breath before the release.

And courage—it doesn’t wear armour here. It looks like standing your ground when the shot matters. It looks like showing up when your confidence’s gone to shite, and the only thing keeping you from walking off is that small, unspoken promise you made to yourself.

Then there’s temperance. That’s the soft one. The one that whispers instead of shouts. It’s what holds you back from rushing. From chasing glory when the body’s begging for rest. From letting joy or anger flood the system. It’s what tells you: hold steady. Stay with it. One arrow at a time.

Discipline wraps round all these like thread in a loom. It’s the rhythm of your training, the early mornings, the days you’d rather not. It’s trusting the process even when it feels like you’re going backwards. It’s the part of you that says: this matters, and I’ll give it what it asks.

And there’s respect. Not just for the gear or the game, but for the people who taught you, who stood by you when you missed and missed again. For the old hands who shaped this craft before you were born. For the silence. For the land you shoot on. For the stories that live in the string and the shaft.

All these—patience, courage, temperance, discipline, respect—they’re not medals. They’re markers on a path. They show up in how you stand, how you speak, how you miss and how you mend.

Even your stance becomes a kind of wisdom. Too wide and you’re stiff as a statue, all muscle, no flow. Too narrow and you’re all nerves, swaying in the breeze. Somewhere between lies balance. A mean, as Aristotle would say. Not average—but true.

Same with the draw. Pull too little and the arrow limps. Pull too much and the muscles quake, the mind scrambles. But find the sweet spot—the place where strength meets ease—and the shot sings.

That’s the Golden Mean. Not the middle, but the moment where things work just as they should. It’s not about holding back or going soft. It’s about knowing your measure.

And when you find that rhythm—not just in your body, but in your choices, your voice, your whole way of showing up in the world—that’s when you touch something real. That’s aretē. Not once-off brilliance. But the lived, earned excellence of being who you are, and doing it well.

And here’s where the real craft begins—not in the form alone, nor even in the virtues built through habit, but in the wisdom to know what fits where and when. That’s phronēsis, though the word itself hardly matters. What matters is what it points to: a way of seeing, not just with the eyes, but with something deeper.

It’s the part of the archer that knows how to read the wind, not just measure it. That watches the clouds and thinks not only of weather, but of mood, of breath, of rhythm. It’s what tells you when to hold and when to loose. When to keep going and when the hands have had enough. It lives in the gut, sure—but it’s shaped by time, by failure, by paying attention when others looked away.

It’s not theory. You don’t get it from books. You earn it.

I remember a day out in Kilmashogue, a field shoot with a wind that changed its mind every ten seconds. Most were fighting it, trying to muscle through. But there was this one lad, older than most, quiet. Watched the grass more than the flags. Adjusted his stance between every shot like he was listening to something the rest of us couldn’t hear. And he shot clean. Not because he had better gear, or even better form—but because he knew when to trust stillness and when to bend with it. That’s what we’re talking about.

Phronēsis is knowing what excellence looks like in a given moment. It’s not some grand idea you hold in your head—it’s the lived feel of what’s good and what’s good enough. It’s the call you make when the sun’s in your eyes, or your shoulder aches, and you still want the shot to count.

It also tells you when you’re lying to yourself. When you say, “Just one more,” even though your hands are trembling. When pride whispers to push through, but wisdom says: rest. It’s the awareness that the body isn’t a machine, and neither is the mind.

An archer with phronēsis doesn’t just shoot well—they live well in the act of shooting. They adapt. They respond. They move through uncertainty with a kind of calm that’s born from being present, not perfect.

And the world won’t always offer stillness. You might have good form, strong habits, clean gear. But then the pressure creeps in. Maybe it’s a crowd. Maybe it’s a score that matters too much. Maybe it’s just your own thoughts, tangled like weeds. That’s where practical wisdom earns its keep.

It tells you how to hold focus without gripping it too tight. How to notice fear without giving it the reins. How to hold confidence like a flame cupped in the hands—not too loose, not smothered.

And it’s this balance, this fluid steadiness, that links every part of the archer’s work—the moral with the mechanical, the spiritual with the technical. You’re not just chasing the gold ring on the target. You’re learning how to meet the world as it is, moment by shifting moment, and do what’s best with the hand you’re holding.

That kind of wisdom spills out from the range into the rest of life. It teaches you how to speak kindly when you’d rather bite. How to let go of a plan when the tide turns. How to choose well in the thick of it, not from certainty, but from a grounded trust in your own learning.

So the archer’s life, if taken seriously, becomes something greater than a game of points or pride. It becomes a way of being, shaped by the slow fire of experience, and lit by a lantern of hard-won judgment.

And maybe, in the end, that’s the true shot. Not the one that hits centre, but the one that’s loosed with intention, steadiness, and just enough courage to call it your own.

When the wind rises during a match and the clock ticks like a pulse in your teeth, phronesis whispers steady. It tells the archer when to hold and when to let fly. It knows that some risks are born of courage, and others of panic. And in that small knowing, a shot can be saved—or squandered. This wisdom, practical and earned, isn’t the kind you carry in your head like a rulebook. It’s the kind that lives in your bones. It grows in you the way moss finds the north side of stone.

The target may stay fixed, but the world doesn’t. Wind shifts. Pressure builds. And what worked on Monday feels strange on Wednesday. That’s where phronesis shines—when rote falls short and presence must step in. You feel the draw in your back, not because it’s correct, but because it’s right for now.

That’s the thing about the Golden Mean—it breathes. It’s not a line drawn once and forever, but a mark you learn to find again and again. In focus, it’s that quiet place between distraction and obsession. You see the whole shot—light, wind, heartbeat—and not just the bullseye. In confidence, it lives between doubt that stutters your hand, and pride that blinds your sight. True confidence walks with you. It doesn’t shout. It doesn’t flinch. It simply stands.

And all of this—this thoughtful striving, this learned balance—draws the archer toward something greater than medals. Aristotle called it eudaimonia. Not joy for its own sake, nor ease of living, but a life shaped around purpose, virtue, and the honest work of being fully alive.

It’s the kind of life that grows from doing things well. Not just technically, but truly. The archer doesn’t flourish because every arrow finds gold, but because each shot is an honest effort to align action with intention. They draw the bow not for applause, but because each draw is a chance to meet themselves again—and maybe, in time, become someone worth meeting.

There’s a quiet gladness in that. A joy not made of moments, but of meaning.

You feel it when the shot breaks clean and the world goes still. You feel it when form and thought and heart sit together like friends at dusk. You feel it when you miss, but miss well—because you knew the wind, and still you tried.

And so, if technē teaches the hands, and aretē shapes the heart, it is phronesis that sees the world and says, “Now is the time.” It draws from memory, yes, but acts in the moment. It knows that the best shot isn’t always the boldest, or the safest, but the one most fitting. The one that fits you.

And over time, that wisdom moves beyond the range. It walks with you. In hard talks. In quiet grief. In small kindnesses done without thinking. The archer who learns phronesis learns how to live—not just shoot.

So we circle back now, to where we began. To Plato’s Ideal. To Aristotle’s grounded path. The philosophical archer is born from both. They carry the dream of a perfect shot, yes, but walk toward it step by step, arrow by arrow, day by changing day. They know the cave, and the light. They know the fire of the spirited soul, the tug of the appetite, and the calm hand of reason that must guide the lot.

They train not only for competition, but for clarity. They master form not for applause, but for the sake of doing something well. Because in doing it well, they meet the world without flinching. Because in drawing the bow, they learn to draw themselves toward something worth becoming.

And perhaps, just perhaps, they find in this practice not just the echo of excellence, but the sound of a life being lived fully—arrow by arrow, choice by choice, silence by silence.

From Aristotle, the archer gains a steady footing. A reason to rise each morning and pull the bow again. Telos, he says—know what you’re for. And the archer, standing alone on a soft hill or inside a crowded hall, knows it plain: they’re here to shoot well. Not for spectacle. Not even always for result. But because the act itself holds meaning. Done with care, with virtue, with patient return—it shapes the life around it.

It’s a kind of energy, that repeated gesture, that pushing toward something better. And each small virtue built into it—be it courage, patience, or restraint—grows not by magic, but by doing. Over and over. Day by day. The Golden Mean walks alongside you. You find it in the steadiness between ambition and contentment, between force and fluidity, between care and courage. And guiding that walk—sure as dawn—comes phronesis, practical wisdom. The inner compass. The tactful eye. The quiet voice that knows this day is not like the last, and adjusts without complaint.

But if it ended there, it would feel like clay without fire. So we turn, then, to Plato, and suddenly the shot is not just a thing done well—but a thing dreamt true. His Ideal Shot hangs just beyond reach—not to tease, but to lead. A shot that lives outside the mud and wind, pure in form, perfect in aim, as if it was always meant to be.

That’s where the magic stirs. For what’s practice without poetry? What’s craft without a horizon?

And here the archer finds themselves between worlds. On one hand, they build skill with the brick and mortar of sweat and time. On the other, they reach beyond the seen, toward something unnameable that still calls.

And the strange thing? These worlds don’t quarrel. Plato dreams. Aristotle builds. And together, they shape a practice that’s both noble and real. The ideal gives meaning to the method. The method keeps the ideal from drifting into mist.

The archer walks between them—feet firm, eyes lifted.

The Platonic vision gives them aim. It whispers of perfection, not to taunt, but to guide. The Allegory of the Cave reminds them to question, to move toward light even when the shadows feel safer. The tripartite soul teaches them balance: reason steering the chariot, spirit lending fire, appetite kept in check with kindness.

But it’s Aristotle who walks beside them in the field. He reminds them that virtue isn’t imagined—it’s earned. That excellence is something done, not just understood. That phronesis isn’t about knowing right, but about choosing well, again and again, in the real weather of a lived life.

And those two ways, once thought divided, begin to rhyme. Together, they give the archer not just direction, but depth. Not just a craft, but a calling.

Scholars have long tried to draw lines between the old masters. But when you’re holding the bow in your own hands, the lines blur. What matters is this: Plato offers vision. Aristotle offers the map. And both point toward a kind of life that’s shaped by care, guided by thought, and elevated by beauty.

You see this harmony not just in books, but in bodies. In archers who know the rules yet move like artists. Who shoot not just for points, but for truth. Who find joy not only in winning, but in doing something as well as it can be done.

This is the philosophical archer.

They do not cling to one path, nor do they wander lost between many. They hold the tension between ideal and real. They stand where form meets function. They draw toward a centre that lives both inside and just beyond the ring.

And when they shoot—when they truly shoot—it’s as if the arrow carries a little bit of both worlds: the shape of perfection, and the weight of practice.

That, perhaps, is what it means to live well.

The philosophical archer, then, is not simply one who shoots straight. Nor are they content to polish technique like a coin in the pocket, nor drift through dreams of unreachable ideals with their feet dangling off the ground. They’re something else entirely. A rare weave of mind, body, and something like spirit. A person who lives within their craft as one might live in a beloved landscape—part habit, part hunger, part quiet awe.

They don’t practice by rote. Nor do they float in theory. Their art lives in the middle ground, where breath meets aim and thought meets action. Each draw of the string, each steady release, carries with it a kind of invocation—of Plato’s vision, bright and distant, and Aristotle’s grounding, solid and clear.

It’s a kind of pilgrimage, surely, but not one that moves from place to place. It’s a journey taken in circles. In practice sessions that repeat but never repeat. In misses that teach, in hits that test the ego. In the learning of wind, and weight, and will.

The Platonic Ideal, that perfect, unerring shot, hangs always just ahead. Not to tease, but to lead. It reminds the archer why they began. It holds them to a higher standard. It gives shape to the longing that keeps them coming back to the range when the weather’s rough and the body aches.

Yet, without Aristotle’s clear-eyed wisdom, that ideal might become a burden. A star too distant. But with the virtues forged through time—discipline, patience, courage—and the gentle clarity of phronesis, the archer learns to move toward the ideal without breaking themselves against it.

And this is the miracle of it—the archer lives between the eternal and the changing. Their form, learned and relearned, becomes a ritual. Their failures, folded into memory, become teachers. Their patience, tested in silence, becomes strength. And all the while, they grow. Not simply more skilled, but more whole.

They learn to temper ambition with humility, drive with kindness. They come to see that the bow is not just a weapon or a tool, but a mirror. Each shot reveals something—about control, about letting go, about presence, about fear.

And isn’t that the deeper purpose? To become the kind of person who can hold tension and grace in the same hand? Who can respond to pressure without losing sight? Who can aim at something beautiful and try—earnestly, imperfectly—to reach it?

Without the dream of the ideal, the practice would lack soul. Without the ethics of practice, the dream would drift like mist. But together—together they make something worth returning to.

The philosophical archer, then, becomes a witness to their own unfolding. Each day’s shot part of a longer song. They may never arrive at the Perfect Shot in full—but in trying, again and again, they become something rare. Someone who aims with clarity. Someone who acts with care. Someone who knows the weight of the bow and bears it willingly, because it teaches them how to live.

And so they step to the line. They plant their feet. They breathe. They aim.

And in that moment—short as a heartbeat, quiet as a thought—the whole world holds its breath, and they become, for a flicker, the very thing they seek.

Not just an archer.

But one who remembers what it means to be fully alive.

This article is part of our free content space, where everyone can find something worth reading. If it resonates with you and you’d like to support us, please consider purchasing an online membership.