What travelled farther: the bolt that left the string, or the hand that held the string and trembled, deciding, for a heartbeat, whether mercy had any jurisdiction over hunger?

Quid longius it: telum an animus? A question suited to a stone porch where sandals rasped across dust, while an olive’s thin shade behaved like a short commandment. Aristotle had weighed βουλή—deliberation—as the hinge of action, while the tragedians had shown the hand serving the heart while also betraying it; the weapon, held for a moment, drew those quarrelling doctrines into one muscle, so that intention grew visible in the wrist, mercy argued with hunger in the throat, and the world waited for the small click that made thought irreversible. The bowstring, once drawn, resembled a moral syllogism under strain: premise held, consequence waited, conclusion already lived inside the strained curve.

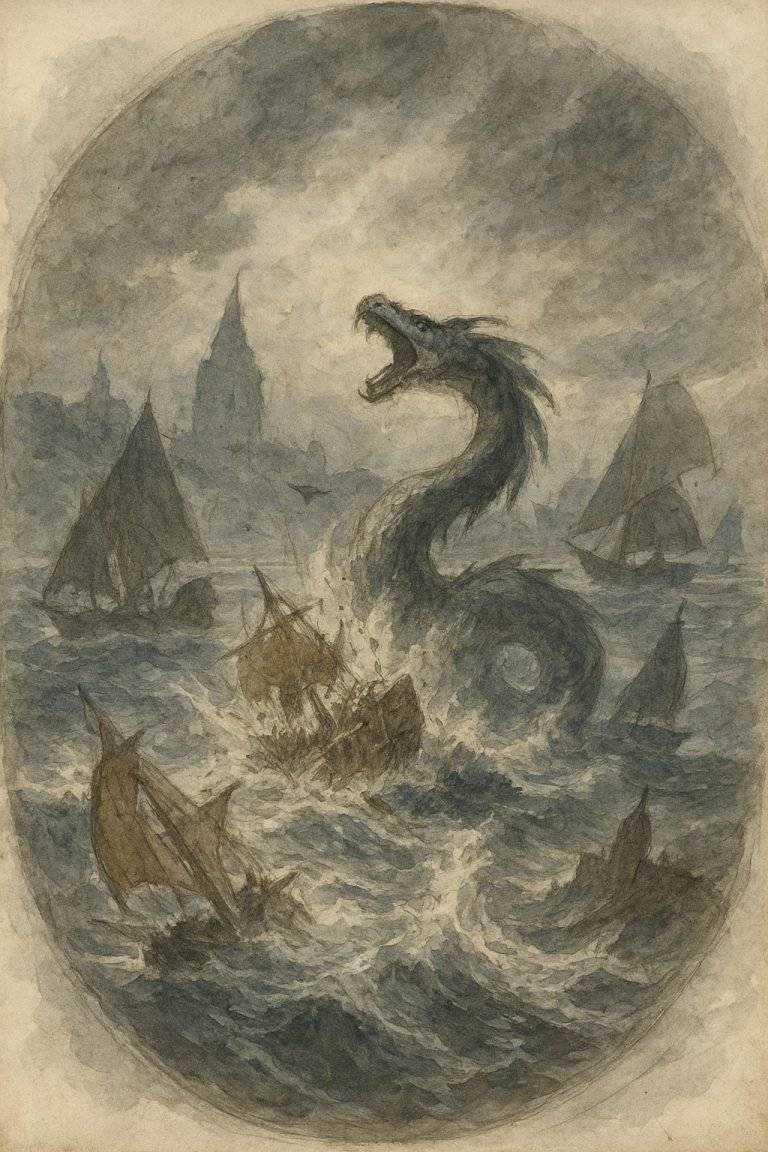

Coleridge, writing at the threshold where the old ballad mind met a newer arithmetic of empire, placed such a moment—brief, clean, almost casual—into the centre of his marine nightmare. In The Rime of the Ancient Mariner the listener got seized at the wedding door as though fate had acquired fingers; the tale began as compulsion and masqueraded as hospitality.¹ The poem’s violence toward the albatross arrived through a hunter’s gesture: a crossbow raised, a bolt released, a white bird struck. That act carried the peculiar sin Romanticism recognised too well: freedom injuring what had offered guidance, companionship, even blessing. The crossbow mattered as a form, given that it stood between bodily discipline and mechanical permission, between the long labour of the draw and the quick authority of a trigger; it belonged to craft and contrivance at once. A question opened beneath the narrative like a trapdoor: when a human being acted through an instrument that multiplied intention, whose soul owned the damage?

The archery scene carried a double charge, one historical and one metaphysical. In historical terms, the poem emerged at the hinge of voyages and ledgers, when oceans had begun to serve as corridors for capital and conquest, while the sea retained its older Gothic character as a space of omen and sacrament. The wedding guest stood as a figure of settled social time—music, kinship, ritual—whereas the mariner functioned as the revenant of expansion, a man returned from the outward motion that made ports rich and minds restless. Seamus Perry’s account of the poem’s early placement at the head of Lyrical Ballads foregrounded the deliberate shock: a book seeking sympathy and a new poetic diction opened with an ordeal of superstition, weatherless dread, and spiritual penalty.² Coleridge and Wordsworth, in their famous division of labour, had agreed that one would court “persons and characters supernatural,” while the other would make the daily strange by attention; that pact furnished a structural explanation for why a bird could enter as natural creature and liturgical emblem together.³

A reader sometimes treated the albatross as an allegorical convenience—innocence, Christ, nature, conscience—while the poem kept insisting upon the bird as an event, a body, a presence with weight and appetite. Its arrival occurred inside a hard theatre of ice and risk, where the crew’s life depended upon movement and wind. The poem gave the entrance a ceremonial cadence that sounded like folk-prayer and shipboard protocol braided into one voice.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

At length did cross an Albatross,

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God’s name.

The lines placed terror and welcome into the same breath. That “Christian soul” phrase did more than baptise a bird; it showed a culture using theology as a survival tool, since sailors carried superstition and prayer as practical devices for enduring a world whose scale mocked human mastery. The poem also performed a darker recognition: reverence could spring from need, and need could sour into cruelty, as though piety and appetite shared a bed and kept kicking each other awake. The mariner’s later suffering therefore unfolded as a conflict between two economies of value—instrumental reason counting outcomes, sacred imagination counting offences—each demanding sovereignty over the same act.

The weapon’s feel in the hand sharpens the ethical discomfort. A longbow asked for a trained body, a full draw, a visible labour; a crossbow, through spanning devices and stored energy, released power by a trigger, granting a kind of mechanical permission. The instrument seemed to promise distance between intention and impact, even while the bolt travelled as the hand’s emissary. When Coleridge placed the killing inside a line that behaved almost like an aside, he intensified that uneasy ease; culpability entered syntax as though it had slipped into speech.

The Albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariner’s hollo!

In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine;

Whiles all the night, through fog-smoke white,

Glimmered the white Moon-shine.

‘God save thee, ancient Mariner!

From the fiends, that plague thee thus!—

Why look’st thou so?’—With my cross-bow

I shot the ALBATROSS.

The stanza staged hospitality, then turned hospitality into rupture. The bird came “for food or play,” so the act carried a betrayal of trust before it carried any symbolic load. The “vespers” line gave the albatross a ritual appointment with the ship, as though the rigging served as choir-stall; the crossbow shot then read as sacrilege without requiring doctrinal explanation. The moral economy that followed refused any polite proportion: the crew swung from approval to condemnation, as though conscience functioned like a weathercock. The later hanging of the carcass around the mariner’s neck performed communal judgment with the brutality of a penance rite: guilt turned visible, internal shame turned into public object, sin given a costume.

A Romantic poem, in other hands, might have offered the hunt a pastoral gloss, a noble cruelty, a mythic glamour of the archer as hero. Coleridge refused consolation. The crossbow carried the chill of arbitrariness. The mariner offered motive only as impulse, and that emptiness—an ethical vacuum where narrative expects reason—became the poem’s deepest terror. A world in which violence arrived through articulated motive permitted debate; a world in which violence sprang from uncaused appetite dragged the mind toward the older theological register where sin looked like inheritance, and desire looked like disorder. Augustine had described an interior rebellion, a mind commanding itself and meeting resistance; that model of fractured agency suited Coleridge’s mariner with uncanny fit, given that the mariner’s later compulsion to speak resembled conscience seizing the tongue as instrument. The poem, older than Freud, behaved like a case history of repetition: a man haunted by an act, driven to restage it through narrative, compelled to choose strangers as witnesses, given that solitude offered a courtroom without adjournment.

Jerome McGann’s account of the poem’s meaning offered particular help here, because it resisted a purely private psychology. McGann treated the work as an artefact whose force shifted across time, and as a moral narrative whose authority resembled a salvation story filtered through modernity’s crises; under that lens, the crossbow became a historical hinge, a technology of killing belonging to hunting and war, carried into a poem that also belonged to a literary revolution.⁴ Timelessness therefore failed as an explanation. Romanticism loved the medieval, and the ballad form flirted with archaic diction, yet the crossbow also echoed a Europe that had begun to mechanise violence in thought, even before factories mechanised it in steel. The poem’s spell depended upon that tension: archaic surface pressed against modern dread.

Coleridge’s later marginal glosses sharpened the drama of interpretation as a moral act. A stern cleric seemed stationed at the page’s edge, offering judgments that both guided and constrained the reader’s sympathy; the gloss behaved as the poem’s conscience speaking beside the poem’s dream. That editorial impulse—Coleridge’s own hand policing Coleridge’s own vision—mirrored the narrative’s central wound: a man seeking order after a gratuitous breach, while the breach kept reopening. The poem therefore held two Romantic impulses in one body: imaginative excess, and ethical law. Each impulse tried to master the other, while the sea refused mastery.

The hunting moment also exposed politics, though it did so sideways. The late eighteenth century watched revolutions claim liberty while blood travelled in bureaucratic channels; Europe learned that noble rhetoric could ride atop organised killing. A crossbow bolt flying into a bird’s body became, within such a climate, a miniature emblem of a wider condition: the ease with which a body pierced another body, followed by the difficulty of living with the fact. The crew’s shifting verdict resembled societies that applauded violence while it served appetite, then sought scapegoats when consequence arrived. The hanging albatross functioned as scapegoat-sign and confession-sign together: accusation displayed upon a single chest, communal relief purchased at the price of individual torment. A civic sermon hid in that grisly jewellery.

William Empson’s reading suited the archery question, because Empson refused moral tidiness and treated the poem’s theology as a field of pressures.⁵ His attention to doctrinal contradiction—pity pressed against severity, grace pressed against terror—kept the crossbow act from collapsing into a single emblem. Under Empson’s gaze the poem’s moral world behaved as argument in motion: cosmic justice cohabited with arbitrary suffering, prayer arrived through fear, and the universe’s moral arithmetic remained disturbing. The disproportion between act and penalty became central, forcing attention to questions of justice and the role of suffering in moral education. The albatross scene, for Empson, served as the switch that threw the entire system into crisis; the crossbow acted like a small lever capable of moving a heavy metaphysical weight.

Psychological texture deepened the unease. The mariner’s “bright eye,” his “strange power of speech,” his agony that forced confession, resembled a trauma-bearer denied the comfort of forgetting. Freud would later describe repetition as an attempt to master a shock that overwhelmed the psyche; Coleridge dramatised that mechanism through a character condemned to narrate, as though speech functioned as a ritual that temporarily kept madness at bay. The archery moment therefore became an origin scene of a psychic loop. Each retelling functioned as a fresh drawing of the bow: tension gathered, aim fixed upon a listener, release delivered through words, followed by brief relief, followed by the next compulsion. The poem’s frame enacted that loop formally. A wedding guest sought joy, yet got arrested into witness; the mariner sought relief, yet received only the continuing duty to speak. A wound travelled by voice.

The crossbow’s cultural history thickened that moral-psychological argument. Britannica’s account described the crossbow as a leading missile weapon of the Middle Ages, with groove, sear, and trigger; its outlawing for use against Christians by the Lateran Council of 1139 revealed how the weapon’s efficiency frightened moral authorities.⁶ That history mattered, because it placed Coleridge’s instrument inside a tradition of anxiety about technology that levelled skill and multiplied harm. The weapon belonged to hunting and sport as well as war; it therefore carried the cultural memory of controlled killing, of leisure tied to death, of aristocratic pastime and peasant necessity. In Mariner the crossbow entered a maritime setting where a gun might have fit; Coleridge’s choice therefore carried deliberate resonance. The mechanism invited a gesture that felt both intimate and detached: intimate through proximity, detached through trigger. The poem’s later suffering crushed any fantasy of detachment by dragging the mariner into embodied misery until thirst turned his mouth into a cracked instrument.

The Metropolitan Museum’s study of European crossbows supplied the object’s material life: workshops, spanning devices, opulent decoration, use across social classes, even the presence of women and children among users in certain contexts of hunt and competition.⁷ Such details removed the crossbow from abstract symbol and restored it as crafted thing, loved as artefact, feared as penetrative tool. Romanticism admired craft, while also fearing the uses to which craft bent; Coleridge, attentive to rope and mast and shroud, would have felt the weapon’s carved stock and taut cord as part of the poem’s tactile world. The crossbow therefore became an index of human ingenuity devoted to rupture. Beauty got recruited into harm.

The albatross itself carried a sociocultural archive that extended beyond Coleridge’s page. BirdLife International’s account of albatross myths recorded long maritime beliefs treating albatrosses as luck-bringers, mystery-bearers, and objects of reverence among seafarers.⁸ Such lore clarified the poem’s ethical atmosphere: harm to the bird did more than harm a creature; it violated a covenant between voyager and sea-world. The bird arrived as companion and helper, and the shot violated hospitality, an ethic older than Christianity: gift betrayed, guest killed, welcome inverted. When the carcass hung around the mariner’s neck, the poem staged reversal with grotesque elegance; the host bore the guest as corpse-sign, a kind of anti-sacrament. Even the later idiom “an albatross about one’s neck,” traced in lexicography, carried the poem’s cultural afterlife, proof that a single crossbow shot had entered the language as durable moral burden.⁹

The poem’s philosophical nerve began to pulse most strongly where ethical frameworks collided. A utilitarian calculus would ask what gain the crew secured: food, safety, amusement; the poem offered none, and that absence sharpened guilt. A deontological ethic would ask what rule got broken: reverence for life, respect for omen, obedience to providence; the poem multiplied possible rules and withheld final settlement. A virtue ethic would ask what sort of character killed from idle impulse, and what formation produced that impulse; Coleridge offered hints—boredom, bravado, a culture of testing power—while leaving motive shadowed, as though the act rose from freedom’s abyss. Romanticism, which often celebrated freedom as creative power, faced its darker twin here: freedom as the capacity to wound without reason.

The surrounding narrative intensified the knot. The ship entered the ice, and the albatross arrived as rescuer, a sign of movement and wind; after the kill, the ship stagnated under a pitiless sun, and tongues dried. The world behaved as though it participated in moral law, as though nature enforced covenant; yet the poem also showed nature as terrifyingly indifferent, since the sea rotted, the air failed, and bodies fell. That mixture—moralised nature mingled with indifferent nature—created the poem’s peculiar theology, where providence felt present while also opaque. Coleridge, steeped in Christian imagination while troubled by political disappointment and philosophical doubt, encoded that trouble as a cosmos that answered and refused answer at once.

If the poem ended as a simple repentance narrative, the archery theme would settle into fable: kill a sacred bird, suffer, learn love, gain absolution. Coleridge withheld such neat closure. The mariner received relief when blessing rose within him “unaware,” yet the sentence of wandering remained; penance outlived the moment of grace. The endurance felt psychologically accurate: pardon could arrive, while memory still burned. The endurance also felt philosophically sharp: an ethical breach altered the self, and the alteration persisted as identity. Romantic self-fashioning, so often celebrated in the era’s rhetoric, encountered self-deformation.

The turning point—love springing up where disgust had ruled—arrived through attention to creatures previously despised. The poem rendered the scene with a sensuous precision that made moral change feel like perception changing its clothing.

Beyond the shadow of the ship,

I watched the water-snakes:

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire.

O happy living things! no tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessed them unaware.

The mariner’s blessing occurred without calculation; it resembled grace arriving through the senses, as though the eye’s education could convert the will. Yet even here the poem refused sentimental ease. Spirits still prowled, punishment still pressed, and the mariner’s future remained yoked to compulsion. The scene therefore functioned as philosophical pivot without functioning as narrative absolution. Love entered, and consequence stayed.

Form carried its own argument. The ballad stanza’s alternating measures behaved like drawing and release: a longer line stored breath, a shorter line discharged it, while rhyme returned as insistence, as though the mind kept circling the same wound. The frame narrative—a guest halted on the way to celebration—made reading itself resemble ethical interruption. The mariner aimed his speech as an archer aimed a shot: he fixed a target in attention, and he hit. A listener became captive, then transformed. The poem’s final effect upon the wedding guest—sadder, wiser—suggested infection, as though guilt travelled through narrative the way salt travelled through timber.

Sociocultural grounding sharpened the terror. Britain in the 1790s lived under naval war, maritime trade, press-gangs, shipwreck, and the moral pressures of empire. Sailors carried taboos and superstitions as practical survival ethics, ways of imposing order on vast uncertainty. Harm to an omen-bird, within such a culture, invited dread with an inevitability that felt communal. Coleridge honoured sailors’ lore while exposing its psychological architecture: belief functioned as shared grammar of fear and belonging, and that grammar could turn violent when threatened. The crossbow kill therefore functioned as breach of communal contract as well as breach of divine order. That dual breach explained the crew’s rage, and it explained the poem’s insistence that one man’s impulse could poison an entire ship’s moral climate.

A final knot remained: agency. Who killed the bird? The mariner said “I,” and that confession anchored responsibility. Yet the poem also staged forces operating through him: boredom, impulse, perhaps a darker metaphysical lure. Glosses framed events as providential, while providence could feel like language for the overwhelming. When a person committed harm, language sought causes that softened culpability—upbringing, mood, fate—yet the poem stripped away most comforts by insisting upon consequence. The crossbow therefore functioned as philosophical emblem: an instrument amplifying intention while tempting the user to treat the outcome as mechanical. The mariner learned, through suffering, that mechanism offered no asylum from guilt.

Now the opening riddle returned to demand payment. The bolt travelled through a short corridor of air and ended in feathers and blood; its journey belonged to physics, and physics ended quickly. The hand, however, travelled through years, through thirst and corpse-light, through a lifetime of compelled address, through the slow ruin of knowing that one moment’s aim could reshape a soul. The bolt ceased; the hand kept moving, dragged forward by memory and compelled into confession. The farther voyage therefore belonged to the trembling hand, and to the conscience behind it, since a weapon’s release ended in seconds while moral recoil entered strangers’ eyes and continued under the name of guilt.

Yet even that answer carried a bruise, since the mariner’s story crossed into other minds and kept travelling as shared burden. One crossbow shot, placed by a Romantic poet inside a ballad frame, continued its flight through idiom, interpretation, and cultural unease, as though the bolt had failed to land and instead lodged in language itself, tugging at the throat in every age that spoke of hunger and mercy as rival sovereigns.

Scholia:

¹ Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (text of 1834), in The Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Ernest Hartley Coleridge (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1912), pp. 187–230.

The 1834 form, stabilised in later collected editions, matters for an argument centred on the crossbow because it preserves the killing line’s abrupt moral nakedness while surrounding it with a maturely managed architecture of penalty and compulsion. The stanza containing “vespers nine” and the shot binds the bird to ritual time, which intensifies the act as sacrilege without requiring explicit doctrinal exposition. The frame narrative’s coercive intimacy—an old sailor arresting a wedding guest—turns the poem into an enacted confession, so that guilt functions as social force as well as private wound. Reading the 1834 text through E. H. Coleridge’s editorial context also keeps revision in view: Coleridge’s later mind sought order through gloss and adjustment, yet the core shock persisted. The crossbow act therefore remains the poem’s ethical fulcrum: an engineered release that pretends ease, followed by a lifetime in which ease proves unattainable.

² Seamus Perry, ‘An introduction to “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”,’ in Romantics and Victorians (London, The British Library, 15 May 2014), accessed 25 January 2026.

Perry’s contextual account clarifies why the poem’s archery moment belongs to literary history as well as to narrative. Lyrical Ballads had announced a new seriousness about ordinary speech and sympathetic attention; placing a sea-haunting, omen-charged ordeal at the book’s threshold created a deliberate affront to polite expectations. That affront renders the crossbow shot more than plot device; it acts as manifesto in miniature, declaring that moral imagination would operate through fear, superstition, and spiritual penalty as readily as through pastoral calm. Perry also emphasises the poem’s pattern of sin, suffering, and partial redemption, which frames the albatross killing as inaugural breach generating an entire penitential economy. A seminar room often inherits the temptation to treat the albatross as a tidy emblem; Perry’s focus upon publication context and readerly shock restores the act’s social sting: violence against a welcomed creature threatens a community’s fragile order, then forces that community into scapegoating and interpretive panic.

³ Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, ed. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate, 2 vols (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1983), I, pp. 130–138.

Coleridge’s retrospective account of the plan behind Lyrical Ballads offers a rare authorial articulation of method that illuminates the crossbow scene’s double register. The albatross enters as natural creature within a harsh ecology of ice and risk, while also functioning as omen and liturgical guest, so that the poem fulfils the project Coleridge described: rendering the marvellous psychologically persuasive through “poetic faith.” The crossbow shot threatens that faith in a paradoxical way, since cruelty requires no supernatural licence; the reader’s moral recoil arises from ordinary human freedom, which then draws supernatural consequence down upon itself. The method therefore intensifies ethical discomfort: the marvellous arrives as punishment for an act that already stands as self-condemnation. Coleridge’s account also helps interpret the weapon choice: a crossbow carries archaic colour, yet its mechanism anticipates modern anxieties about mediation and responsibility, as though technology provided a convenient mask for intention while conscience later tears the mask away.

⁴ Jerome J. McGann, ‘The Meaning of the Ancient Mariner,’ Critical Inquiry, 8 (1981), pp. 35–67.

McGann’s essay strengthens a reading that treats the crossbow act as historically saturated rather than as purely symbolic. By emphasising reception and ideological pressure, McGann encourages attention to the poem’s shifting work across eras: Christian allegory, moral fable, ecological caution, critique of instrumental reason, study of trauma, each reading taking its own aim at the same shot. That interpretive mobility fits the albatross killing precisely, since the act’s apparent lack of motive invites successive cultures to supply motives that reflect their anxieties. McGann also foregrounds the role of later glossing and revision, which frames interpretation itself as moral labour; the crew’s own interpretive volatility—praise turning into blame under stress—mirrors that broader cultural process. Under this lens, the poem becomes a sociology of judgment, where communities seek explanatory narratives to stabilise fear, and where an individual body becomes the site upon which communal anxiety inscribes responsibility.

⁵ William Empson, ‘The Ancient Mariner,’ Critical Quarterly, 6 (1964), pp. 298–319.

Empson’s value for the archery theme lies in his refusal of simple moral arithmetic. He treats the poem’s theology as a pressure system, where grace and terror occupy the same house while quarrelling over tenancy. That approach keeps the crossbow shot from collapsing into a single emblem, since Empson’s attention to contradiction insists that the poem both proposes and undermines pious resolutions. The disproportion between act and punishment becomes philosophically productive: it forces a reader to confront questions of justice, arbitrariness, and the ethical function of suffering without retreating into a comforting logic of “lesson learned.” The crossbow, as engineered trigger, intensifies Empson’s point, since it embodies a fantasy of clean causation—pull, release, impact—while the poem’s aftermath expands causation into spiritual and communal catastrophe. Empson thereby helps articulate why the archery moment feels so unsettling: a small human freedom disturbs an entire cosmos, and the cosmos answers in a language of dread.

⁶ ‘Crossbow,’ Encyclopaedia Britannica (Chicago, Encyclopaedia Britannica, revised 5 December 2025), accessed 25 January 2026.

Britannica’s technological description—stock, groove, sear, trigger—matters for literary study because it clarifies how the crossbow differs from the longbow at the level of embodied ethics. The weapon stores labour, then releases power through a mechanism that can feel psychologically distancing, even while it remains an extension of the user’s intention. The Lateran Council’s association of the crossbow with moral anxiety—its attempted restriction in Christian warfare—reveals a historical fear that technology could equalise killing capacity and weaken older codes of chivalric restraint. Coleridge’s choice therefore carries cultural resonance: the mariner’s act belongs to a tradition of weapons that produced moral controversy precisely because they made harm efficient and accessible. Within the poem, that efficiency appears as moral trap: ease of killing meets an aftermath that denies ease in any form, forcing the reader to consider how instruments reshape responsibility without erasing it.

⁷ Alexander L. Avery and Howard L. Blackmore, A Deadly Art: European Crossbows, 1250–1850 (New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), pp. 1–12.

The Met’s object-centred scholarship helps restore the crossbow as crafted artefact embedded in social practice. The catalogue’s attention to decoration, materials, and spanning devices shows how the instrument could function as status object as well as killing tool; opulence and harm share the same wooden stock. The note that crossbows appeared in hunting and competition across social strata, sometimes involving women and children, complicates any simplistic association between the weapon and a single class identity; the crossbow belonged to leisure, necessity, instruction, and spectacle. That complexity matters for Coleridge’s poem, where a single impulsive shot opens a moral abyss. The weapon’s cultural normality—its presence within organised sport and hunt—underscores the act’s terrifying casualness. At the same time, the catalogue’s emphasis upon mechanism supports the essay’s philosophical claim: mediation through technology tempts the psyche toward a fantasy of clean causation, while the poem insists upon messy, enduring consequence.

⁸ Cintia Baranyi, ‘Albatrosses: Inspiring Legends & Myths,’ BirdLife International (Cambridge, BirdLife International, 19 June 2023), accessed 25 January 2026.

BirdLife’s survey preserves a living record of maritime reverence and taboo that clarifies the albatross’s social meaning beyond Coleridge’s page. Legends framing albatrosses as luck-bringers, spirit-bearers, or mystery-emblems reveal how seafarers used narrative to impose moral order upon an environment whose indifference could feel annihilating. That background illuminates the poem’s ritual vocabulary—hailing in God’s name, vespers perching—and explains why harm to the bird registers as covenant violation. The essay’s emphasis upon hospitality gains force here, since many traditions treat certain animals as guests whose presence carries blessing and whose harm invites curse. In Coleridge’s narrative, the crew’s later scapegoating becomes intelligible as communal crisis response: belief functions as shared grammar, and grammar turns punitive when threatened. BirdLife’s contemporary conservation context also adds a quiet modern sting, though the poem’s ethical core remains anchored in the older seafaring world: reverence, fear, and responsibility braided into one superstition-laced piety.

⁹ ‘albatross, n.,’ Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford, Oxford University Press, online edn), accessed 25 January 2026.

Views: 2

This article is part of our free content space, where everyone can find something worth reading. If it resonates with you and you’d like to support us, please consider purchasing an online membership.