The Lady of Roche

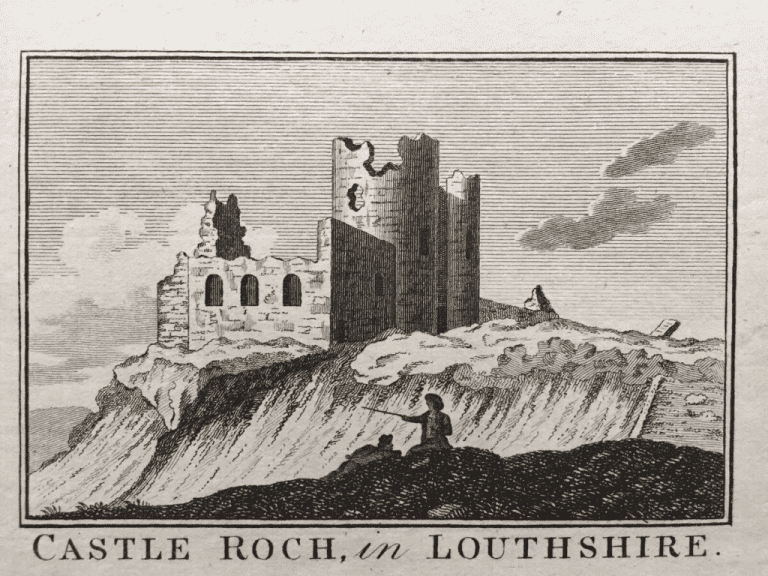

Year of grace 1236 receives a crisp line in the Annals of Connacht, a sentence that carries armed men west with cart, banner, and purpose. Scribes set down the march of the Galls, naming lords, bishops, and kings, a cadence of spears and departures, a ledger where steel, oath, and burial speak in one breath. One world leans upon another across hedgerow and ford, and the record grants that leaning a bright authority. A greater stone rose that same year upon the rough rim of Ulster, a clenched statement of mastery with a woman’s will at its heart, though parchment offered silence where her name should stand. She answered through rock. She signed her life upon a crag that lifts above Louth, a defiant silhouette still blue against evening, a mark that survives every list and every tally. A Latin hand would call it Castellum de Rupe, Castle on the Rock, and that title seals her authorship with a clarity that withstands storm and time.

A house like hers grows from ancient ground. The de Verduns rode from Vessey in Mortaine with the Norman tide of 1066 and pressed on through the marches of Wales toward Irish harbours that smelled of salt and promise. Bertram de Verdun, her grandfather, held the confidence of Henry II and of John. He turned that confidence into acres, into courts, into the kind of revenue that ripens into policy. He crossed with the prince in 1185 and set the line’s anchor where Dundalk greets the sea. Nicholas, his son, sired one heir to receive dominion spread across Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Leicestershire, and Buckinghamshire, with the Irish lordship at Uriel tying sea to shire. That heir, Roesia, understood inheritance as vocation rather than accident. When she joined Theobald Butler in 1225 as his second wife, she looked through the Butler succession and measured her own. Her children would carry the surname that mattered to her line. John de Verdun arrived as testament to that resolve, and the syllables of his name carried a charter’s force. A surname becomes a land when a mind of iron sets the measure.

The life of a lady of that century moved within measured corridors shaped by king, father, and husband. Roesia followed those corridors for a season. Henry III lent personal persuasion to her match, and she honoured the alliance with dignity, bearing children and tending the lattice of families that held the Lordship of Ireland together. Then fate altered the board. Theobald received the summons in 1230, gathered horses and arms, and rode toward Poitou with royal purpose. He died there beneath another sky. Within another year Nicholas also departed the stage. Grief forged a new balance within her and the law offered a name for that balance: femme sole, a woman alone in legal standing, bearer of both burden and advantage. A widow with territories across two realms invites a king’s attention. She answered with treasure rather than supplication. During October 1231 she approached the king with silver for judgment rather than tears for mercy, 700 marks for two prizes: seisin of her patrimony and freedom to choose her own marriage. That figure would clink through any hall. The Exchequer felt the weight, and royal writ answered with grace. By April 1233 the Justiciar in Ireland received order to deliver her lands. She stood with the authority of a magnate and directed her affairs with the steadiness of a steward born to the craft.