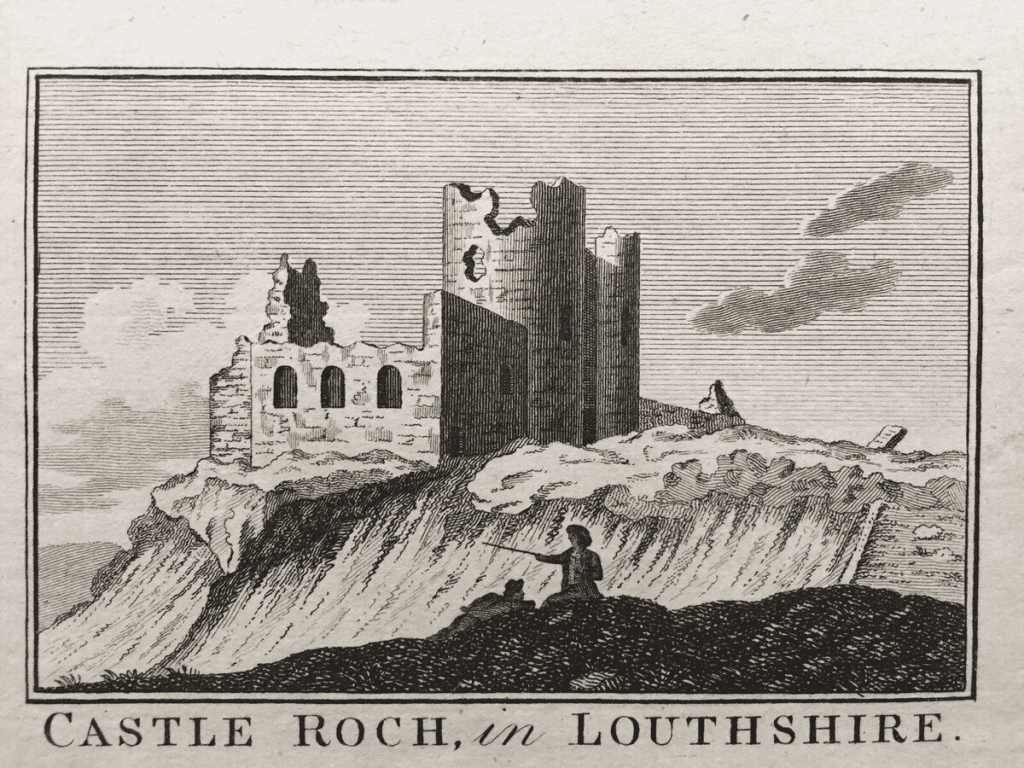

Year of grace 1236 receives a crisp line in the Annals of Connacht, a sentence that carries armed men west with cart, banner, and purpose. Scribes set down the march of the Galls, naming lords, bishops, and kings, a cadence of spears and departures, a ledger where steel, oath, and burial speak in one breath. One world leans upon another across hedgerow and ford, and the record grants that leaning a bright authority. A greater stone rose that same year upon the rough rim of Ulster, a clenched statement of mastery with a woman’s will at its heart, though parchment offered silence where her name should stand. She answered through rock. She signed her life upon a crag that lifts above Louth, a defiant silhouette still blue against evening, a mark that survives every list and every tally. A Latin hand would call it Castellum de Rupe, Castle on the Rock, and that title seals her authorship with a clarity that withstands storm and time.

A house like hers grows from ancient ground. The de Verduns rode from Vessey in Mortaine with the Norman tide of 1066 and pressed on through the marches of Wales toward Irish harbours that smelled of salt and promise. Bertram de Verdun, her grandfather, held the confidence of Henry II and of John. He turned that confidence into acres, into courts, into the kind of revenue that ripens into policy. He crossed with the prince in 1185 and set the line’s anchor where Dundalk greets the sea. Nicholas, his son, sired one heir to receive dominion spread across Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Leicestershire, and Buckinghamshire, with the Irish lordship at Uriel tying sea to shire. That heir, Roesia, understood inheritance as vocation rather than accident. When she joined Theobald Butler in 1225 as his second wife, she looked through the Butler succession and measured her own. Her children would carry the surname that mattered to her line. John de Verdun arrived as testament to that resolve, and the syllables of his name carried a charter’s force. A surname becomes a land when a mind of iron sets the measure.

The life of a lady of that century moved within measured corridors shaped by king, father, and husband. Roesia followed those corridors for a season. Henry III lent personal persuasion to her match, and she honoured the alliance with dignity, bearing children and tending the lattice of families that held the Lordship of Ireland together. Then fate altered the board. Theobald received the summons in 1230, gathered horses and arms, and rode toward Poitou with royal purpose. He died there beneath another sky. Within another year Nicholas also departed the stage. Grief forged a new balance within her and the law offered a name for that balance: femme sole, a woman alone in legal standing, bearer of both burden and advantage. A widow with territories across two realms invites a king’s attention. She answered with treasure rather than supplication. During October 1231 she approached the king with silver for judgment rather than tears for mercy, 700 marks for two prizes: seisin of her patrimony and freedom to choose her own marriage. That figure would clink through any hall. The Exchequer felt the weight, and royal writ answered with grace. By April 1233 the Justiciar in Ireland received order to deliver her lands. She stood with the authority of a magnate and directed her affairs with the steadiness of a steward born to the craft.

With her rents steady and her signature firm, she looked toward the Louth frontier where the Pale met the resilience of Ulster. The O’Hanlons and their neighbours rode that edge with a craft born of hills and glens. Raids followed raids, and cattle paths shouted through the heather. A timber hall would yield to such weather. A fortress would do the speaking. Roesia chose a knifed ridge and demanded a triangular keep that kissed cliff on two sides and set a deep rock-cut ditch upon the third. Castle Roche rose with geometry sharpened by experience. The face toward the approach narrowed into purpose; the gate advanced courage and then trapped it; the wall embraced the precipice like a rider who trusts the horse beneath. Arrowslits lifted tall and slender where longbowmen settled to their work. A yew six feet high fits a man of practice with room to draw clean to the ear. Cross-shaped openings welcomed crossbowmen to kneel, sight, and send a quarrel with weight enough to break through mail and certainty alike. Within every slit the embrasure widened into a pocket of shelter, a stone-walled cradle that turned a soldier into a measured instrument. A passage with four tall slits frowned upon the gate and shaped a true killing ground. That wall spoke fluent arithmetic. Distance, angle, and rate meet there, and any charger who enters leaves history for ballistics.

Archer and mason shared a single grammar there. Consider a guard in jack and sallet, a brace of goose-feathered shafts nodding at his belt. He plants his boots, squares his hips to the line, breathes down the tremor, lifts, settles into anchor, and looses. The hiss of the feathers writes a sentence across the ward. A bolt through a visor or a shaft through a hauberk brings the same lesson: geometry wins a frontier when courage meets practice. The embrasures multiplied that advantage with calm precision. The sightline narrows a man’s world into fate. The bow bears lessons that scholars love: train the body until it sings, trust the angle, trust the wind, trust the instinct that rises from drills and silence and shared breath. Castle Roche converted those lessons into policy. A lordship prospers when discipline meets stone.

Legend climbed the slope as swiftly as the first ivy. A tale speaks of a master builder who won a promise of marriage, then stood with his bride at a high window to admire the lordship his craft had secured, only to meet the long drop below. The Murder Window preserves the gasp. Folklore invents a fall because the people understood the core of her sovereignty. She paid treasure to steer her own course and safeguarded that course with a ruthlessness that mirrors the clarity of her accounts. Another tale places her in hauberk and chausses, helm bright, reins steady, riding at the head of her men toward an O’Hanlon shield wall. Whether her blade drew blood or simply light from the morning matters less than the image of mastery that held the countryside in thrall. She wore command with assurance. She placed fear and reverence in the same equation and balanced them with taxes, charters, and well-posted watch.

Arches often shelter more than spears. Excavations conducted by careful hands under the banner of Revealing Roesia suggest a borough gathered to those walls, a planned settlement with markets and houses, a frontier town that planted ploughs behind a mailed guard. A castle like that answers raids with one hand and counts rents with the other. A field lies quieter when a wall stands firm upon the ridge. Bakers approach the market with steady confidence when warders stand where they should upon the parapet. A parish grows around steady bells, and an English charter makes room for Irish habit. A frontier then becomes a home.

Her will then pivoted toward God with equal measure. Widows of rank received steady pressure toward remarriage. Roesia arranged a finer answer. Between 1239 and 1241 she founded the Augustinian priory of Grace Dieu in Leicestershire. The White Nuns there followed a singular rule and held a dignity that nowhere else in England echoed. She endowed Belton and Louth to the house, creating income and dignity in the same stroke. By 1242 her son John reached his majority. She reached her own decisive harmony. She entered her foundation and wore a veil that sheltered her from any bargaining table. A bride of Christ carries a position that earthly courtiers respect. Her calculation showed elegance. A second marriage would place a fresh lord between John and the full disposal of his heritage. A profession within her own convent freed the estates for straight transfer and secured her final years with prayer, bread, and governance shaped by her own hand.

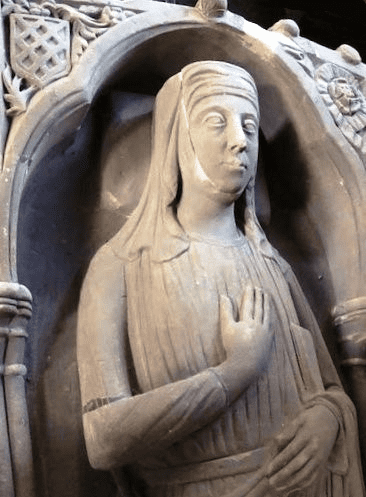

Her death came on 10 February 1247. The sisters laid her within Grace Dieu and sang the offices around the stone. Centuries later the storm of Reformation stripped roofs and altered holdings. The people of Belton answered with fidelity. They carried her effigy to St John the Baptist and set it among their own arches. The sculpture wears serenity. A noble lady lies in grace with hands joined, a shield of Verdun arms lifting above her like a guardian thought. Scholars praise it as one of the earliest representations of that heraldic device upon an English tomb. Across the channel her other monument speaks in a different register. Castle Roche rises from its rock with ragged pride, towers bitten by time yet vigorous as antlers after velvet falls. Stone prays in Leicestershire. Stone bristles in Louth. Both shapes sketch her profile with truthful affection. A long walk upon the ridge today delivers instruction. The curtain wall follows the precipice with absolute composure. The ward opens wide above the fields like a hand held high. From the gorse a skylark breaks, its song weaving high through open air. At the stone slit, a traveller pauses, touched by the mason’s craft still alive within the passing centuries. Latin hands wrote the chronicles. Irish winds keep a parallel record, scribbling across grass and stone. Castle Roche receives both scripts and harmonises them through weather and view. A mind with a bow senses kinship here. The site offers ranges, angles, and cover in a way that speaks straight into a shoulder’s memory. A coach could stand upon that rampart and teach a full clinic with only the architecture as diagram.

Grace Dieu answers from hedgerows and fields with its own timbre. A fishpond flashes where a psalm once met the surface. Orchards remember baskets and laughter. The porter’s lodge remembers low talk at twilight. Charters and court rolls speak their language of quitclaim, rent, and tithe, while the ground speaks blossom, mud, frost, and threshing. Roesia’s choice to step inside her own foundation taught posterity a clean lesson in governance. She transformed a vulnerable station into a plan that favoured both her house and her heir. She demonstrated how devotion can shield estates and how responsibility can secure prayer with grain and timber. A lay steward would admire that balance. A prioress would admire it as well.

A reader of arrows hears further music in her walls. Picture a muster day. Men of the borough stand in ranks with bows unstrung to preserve the sinew. An officer paces with a hazel wand tapping shoulders and elbows into shape. Strings come from pouches, bows bend over knees, and a quiet gathers as discipline replaces chatter. The officer calls distances. A flag flutters in the breeze as a windsock. The first sheaf rises with wings of goose and falls with stump-pulling power. The method repeats until muscle learns law and the mind learns patience. Castle Roche provided a school for such order. Those slits and towers functioned as both weapon and curriculum. The fortress made seasoned archers and also measured how a county learns to breathe under arms without frenzy. A long tradition on this island speaks of the bow with affection and wit. The kern rode quick and fought quicker; the gallóglaigh stood like an oak in armour. English companies prized stave and string. Irish companies prized surprise and song. Roesia’s castle stood where those songs met and traded phrases. The wall loved the longbow’s reach. The glen loved the javelin’s curve. Between them lay a science of survival that any historian of war would recognise with a smile of respect. A wall does more than repel. A wall teaches.

Scholars often measure her against magnates with greater fame in Latin. She stands unshaken beside them. Her genius mapped danger and converted it into order. She read feudal law as opportunity rather than fetter. She layered policy onto geography and extracted revenue from that marriage with elegance. She understood how masonry instructs obedience without cruelty and how markets cultivate loyalty without flattery. She wrote her world through wall, writ, and worship, and the writing survives within two bodies of stone that carry her voice with identical authority in different tones. A statesman learns from that harmony. A poet learns from it as well.

Archery threads this story again and again. Irish kerns valued speed, feint, and daring. English garrisons valued discipline, angle, and range. Castle Roche delivered a stage where both arts performed and learned. The longbow functioned as schoolmaster above that ditch. Boys copied the stance of the guard along the wall and learned to anchor by watching his shoulders. Fletchers enjoyed steady work and goose farms prospered. Yeomen drew strings at practice fields near the borough and weighed distance with finger, eye, and heart. A single fortress educated a countryside toward a union of accuracy and courage.

Time favours designs that fit their ground. Castle Roche appears to grow from the cliff as if limestone itself desired command. Grace Dieu rests in its valley with a peace that fills meadows with light. John de Verdun received full seisin and carried the line into fresh campaigns and courts, precisely as his mother intended. Writers return to her because her life teaches across disciplines. A poet learns cadence from the way serenity and ferocity balance within her two monuments. A lawyer learns economy from the way gift and dissolution arrange a future with unsentimental clarity. A scholar of religion learns reverence from the way enterprise supports prayer without strain and prayer supports enterprise without .A final image carries the full chord. Evening climbs the ridge above Louth. A fine moon sets a pale coin above furze and field. Wind hums across a slit where a longbow once spoke with authority. A rook wheels over the ditch and settles in a copse. The ward lies open like a hand teaching a child how to read the map of a country. Across the water an English parish lifts a winter hymn above an effigy with joined hands, and the two images address each other across distance with an affection earned through labour and resolve. Her life moves between those images with a grace that any traveller can feel upon a single day’s journey.

The chronicles gave few lines to her, while stone gave abundance. Arrows once hissed from her embrasures with the certainty of practiced hands, and chants once climbed the rafters of her choir with the same bright assurance. Between those echoes her figure stands, calm and commanding, a lady who mastered account and strategy, a founder who grew markets and vocations, a patron who married piety to prudence, a ruler whose vision still orders sky and ridge. Readers hold her with gratitude because her life proves that shrewd mercy can plant courage, and that courage can hold a frontier without rage. Scholars, archers, and parish singers gather around her memory and find a single lesson: courage receives shape through structure, and grace receives strength through choice. Castle and convent speak that unity across centuries, across weather, across language, and across lives that step onto that ridge or kneel within that choir with a ready heart for every pilgrim arriving.

This article is part of our free content space, where everyone can find something worth reading. If it resonates with you and you’d like to support us, please consider purchasing an online membership.