This article under the same title is available as an audio podcast, available at Spotifiy and YouTube:

“The Dance of the Manes” at Spotify

“The Dance of the Manes” at YouTube

By Marcin Malek

Welcome everyone to another episode of Winning Paths. Let me guide you through a reality so different, so alien to us that it has been deemed demonic and inherently evil. Join me as we take part in “The Dance of the Manes” — a fierce saga of conflict, culture, and the untold stories of the Americas that we’ve either misunderstood or chosen to ignore.

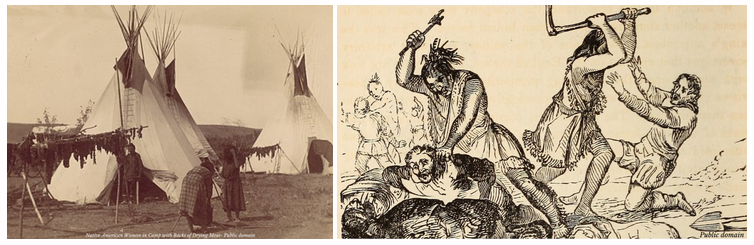

Has history been too kind to the conquerors? Too harsh on the natives? Let’s strip back the layers of the past where the indigenous peoples of both Americas danced a line between life and death, weaving their understanding of the cosmos into the brutal ballet of warfare.

In this no-holds-barred discussion, we unpack how the Native Americans, often misjudged through the ethnocentric lens of European settlers, approached combat not just as a survival strategy but as a sacred duty. From the spiritually charged Sun Dance ritual to the strategic prowess of the Iroquois Confederacy, their methods were as sophisticated as they were misunderstood.

Why did Europeans label these rich cultural traditions as primitive or savage? How did these profound misunderstandings shape the tragic narrative of colonial encounters? And perhaps most importantly, in the face of such adversity, how did Native societies use warfare not just to conquer—but to communicate and maintain a cosmic balance?

Join us as we challenge the conventional narratives, question the written winners, and maybe, just maybe, reshape your understanding of what it truly means to fight for survival. Are you ready to challenge everything you thought you knew about the indigenous art of war? Let the dance begin.

“The world has always been a cruel place, no matter when or where we look, history teaches us that suffering and death are the same companions to human fate as bliss and joy—perhaps even more so.

These two factors—life and death, especially in combat—were fundamental to the indigenous peoples of both Americas. At the same time, it should be pointed out that this is a completely different vision from the one we hold dear by virtue of our origins, one that we can easily understand and morally evaluate.

Native Americans, if they had a concept such as morality, for them it was the result of their perception and understanding of a natural phenomenon rather than a formal system based on the philosophy of enlightened reason.

Which, by no means, makes it any better or worse—it was simply different. So alien and incomprehensible to us that we often attributed to it demonic origins—pointing to the evil nature of the indigenous people of both Americas.

This rift and alienation between the two cultures led, in effect, to the almost complete eradication of the indigenous peoples of North America. Some of the descriptions and facts quoted in this article can be moving, especially for readers with weaker nerves and little resistance to drastic descriptions. I would also like to mention that it was not my intention to subject any of the described parties to any kind of evaluation—all the more so on an ethical/moral level. My sole aim was to enliven the story and light a signpost for those questing…”

Historical narratives often explore the dynamic interactions between indigenous peoples and European settlers, highlighting profound cultural misunderstandings and the tragic consequences that ensued. Native American societies were deeply connected to their surrounding environment, deriving their cultural and ethical systems from an intricate understanding of nature, which guided not only their daily lives but also their approaches to conflict and warfare.

- The Nature of Indigenous Warfare

Indigenous warfare in the Americas was a complex phenomenon that differed markedly from European military strategies and encompassed a broader spectrum of objectives and meanings. Unlike the territorial conquests typically seen in European conflicts, indigenous warfare was intricately woven into the social, spiritual, and political fabrics of Native societies. These conflicts were often sporadic, highly ritualized, and served multiple social functions that went far beyond simple combat or conquest.

For many Native American tribes, warfare was a means of communication within and between tribes, a way to resolve disputes, and a method for managing resources and territories. It was also a vital component of the cultural identity of warriors, playing a crucial role in personal and communal honor. Warfare allowed individuals to earn social status and respect, which were critical in societies where status was not hereditary but earned through acts of bravery and skill.

Tactically, indigenous warfare was characterized by its use of guerrilla strategies. This involved small, mobile groups of warriors who engaged in swift, hit-and-run attacks, ambushes, and surprise raids. These tactics took full advantage of the warriors’ intimate knowledge of their natural surroundings, allowing them to move stealthily and strike unexpectedly. The landscape itself was a weapon, with its features—dense forests, rugged mountains, and vast plains—offering both cover and strategic advantages. The natural environment was not merely a backdrop for military engagements but an integral part of warfare strategy.

This reliance on surprise and mobility highlights a significant aspect of indigenous warfare: its emphasis on psychological impact. By striking quickly and without warning, Native American warriors could instill fear and confusion in their enemies, which were potent weapons in their own right. The goal was often to demoralize the opponent and disrupt their ability to fight back effectively, rather than to engage in prolonged and bloody battles.

Furthermore, the rituals associated with warfare were deeply significant. Before entering battle, many tribes engaged in elaborate preparatory rituals that involved prayers, dances, and the invocation of spiritual protectors. These rituals were crucial for preparing the warriors mentally and spiritually, reaffirming their courage, and ensuring the support of supernatural forces. The performance of these rituals also reinforced communal bonds and prepared the entire community for the potential consequences of warfare.

The ethical framework governing indigenous warfare was also distinct from European norms. Many tribes adhered to strict codes of honor that dictated not only how to fight but also how to treat captives and when to cease hostilities. For instance, some groups believed it dishonorable to kill an unarmed or wounded enemy, and such actions could tarnish a warrior’s reputation and honor. Captives were often taken not merely as slaves but could be adopted into the tribe, filling social or demographic gaps caused by warfare or disease. This practice underscores the fluidity of tribal membership and the potential for enemies to become kin, a concept that was largely alien to European observers.

The misinterpretation of these tactics and rituals by European colonists often led to misunderstandings and intensified conflicts. European soldiers, accustomed to formal battlefields and declared wars, misread the indigenous approach to warfare as primitive or cowardly. This failure to recognize the strategic depth and cultural importance of Native American warfare tactics contributed to the tragic history of violent encounters and the eventual suppression of indigenous military traditions.

In summary, indigenous warfare in the Americas was a sophisticated system that integrated military strategy with social structure, spiritual beliefs, and environmental knowledge. It was not solely about defeating enemies but was a crucial element of social regulation and cultural expression. Understanding the nature of indigenous warfare thus provides key insights into the broader cultural and social dynamics of Native American societies.

- Shortcomings of the indigenous art of war

The weakness of such a system of warfare was its focus on direct and immediate gain. Warriors fought if they hoped to gain loot and fame, and only as long as they felt like it. Rarely did they conduct more complex and protracted campaigns that were thought to yield defined benefits within extended periods of time.

They were incapable of engaging in deep reconnaissance, confining themselves to tracking the enemy, and rarely used overwatch on the march (with the exception of spotters and rearguards, whose job was to ambush the pursuing enemy). They could not understand why the whites attacked in winter, after the warfare season when it was time to rest. They often did not post camp guards, making them easier to surprise in dormant settlements.

- Native American weapons

The most important weapon of the forest Native Americans, used both before and after encounters with whites, was the bow with arrows and the mace of stone or wooden hilt, a highly dangerous weapon in hand-to-hand combat.

The bow and arrows began to be superseded over time by firearms, and the wooden mace was replaced by the steel axe (tomahawk). The Indians quickly recognised the value of the European musket and learnt to use it well.

White traders, especially French and Dutch, were happy to supply them with guns, steel knives and tomahawks in exchange for valuable animal furs. However, even the adoption of firearms did not significantly affect the way the Native Americans fought. Their favourite tactic remained the surprise attack on the isolated settlements of their opponent, who from the mid-17th century onwards was increasingly the European colonist.

- Spiritual and Traditional Foundations of Indigenous Warfare Practices

Indigenous warfare in the Americas was deeply entrenched not only in the material needs of tribes but also in their spiritual traditions and life, imbuing combat with profound symbolic and ritualistic importance. This approach to warfare can be observed across various tribes, where combat was interwoven with spiritual beliefs and traditional practices, providing a rich tableau that demonstrates the complexity of indigenous societies.

Central to understanding the spiritual and traditional dimensions of indigenous warfare is recognizing that many Native American tribes viewed physical conflicts as extensions of their spiritual and cosmological beliefs. War was often seen as a sacred duty, imbued with rituals and accompanied by prayers and ceremonies designed to invoke divine protection and success in battle. These rituals were not mere superstitions but integral components of warfare, believed to influence the outcome of military engagements by aligning the warriors’ actions with the spiritual forces of their world.

For example, among the Plains Indians, warriors engaged in the Sun Dance ritual, which involved dancing, fasting, and personal sacrifice to gain spiritual power for upcoming battles. Similarly, the Aztecs engaged in the Flower Wars, a form of ritual combat designed not only to train warriors but also to capture victims for religious sacrifice, thereby appeasing their gods to ensure agricultural fertility and cosmic balance.

The spiritual dimension of warfare also dictated the conduct of battles. Many tribes believed that the land was imbued with spirits and that specific landscapes held sacred significance. The act of fighting on or for these sacred grounds was often perceived as a duty to protect the spiritual health of the tribe and its territory. For instance, the Apache viewed their homeland as imbued with spiritual power, and defending it was both a spiritual and traditional imperative, intertwined with their beliefs about the land’s sanctity and their place within it.

Warriors themselves were often seen as carrying out the will of the gods or spirits, and their actions in battle were closely linked to their spiritual purity and preparedness. This connection between the warrior’s conduct and their spiritual standing meant that acts of bravery and skill in battle were often seen as indications of divine favor and spiritual superiority. This belief system helped maintain a warrior ethos that went beyond physical prowess to include moral and spiritual dimensions, wherein the true strength of a warrior was measured by their ability to align their actions with the values and expectations of their community and its spiritual traditions.

The treatment of enemies and captives in warfare also reflected complex spiritual and traditional codes. In many tribes, the capture of enemies was not merely a martial success but also had spiritual connotations. Captives could be adopted into the tribe, a process that involved elaborate rituals of death and rebirth, symbolically killing the captive’s previous identity and rebirthing them into their new community. This practice was not only a way to increase tribal numbers but also a profound act of transformation and integration, guided by spiritual principles that viewed enemies as potential kin under the right circumstances.

These spiritual and traditional dimensions of indigenous warfare reveal a sophisticated integration of combat with religious belief, community values, and cosmic order. Far from being random or purely aggressive acts, these battles were conducted within a framework of spiritual significance, where every act of violence was laden with traditional meaning and spiritual purpose. How might our understanding of history change if we viewed these practices through the lens of respect rather than judgment?

- Social and Political Functions of Indigenous Warfare

Indigenous warfare was not only about physical combat but also served as a fundamental instrument of social organization and political strategy across various Native American tribes. This miscellaneous role of warfare helped to maintain social order, enforce tribal laws, and facilitate political decisions within and between tribes.

At its core, warfare was a means of establishing and reinforcing the social hierarchy within tribes. Participation in warfare allowed individuals, especially young men, to attain social prestige and status. Acts of bravery and skill in battle were highly regarded and often resulted in greater influence within the tribal community. This system of merit-based recognition encouraged a culture of valor and prowess, which was crucial for the maintenance of strong leadership and motivated warriors.

For many tribes, the path to leadership roles often necessitated proven competence in warfare. Aspiring leaders were expected to demonstrate their capabilities not only as fighters but also as strategists and tacticians. The respect and authority gained through successful military engagements were critical for leaders to command loyalty and to govern effectively. This linkage between military success and leadership underscored the role of warfare in political structuring within tribes.

Warfare also functioned as a mechanism for conflict resolution. Tribes often resorted to armed conflict to settle disputes over territory, resources, or breaches of agreements. Rather than perpetual hostility, these conflicts were typically conducted according to established protocols, which sought to avoid unnecessary loss of life and to restore peace and order swiftly. The outcomes of these engagements often led to new treaties and alliances, showcasing warfare as a dynamic tool for diplomacy and negotiation.

Furthermore, the control and distribution of resources such as land, water, and hunting grounds were often contingent upon military strength and strategic alliances formed through warfare. Successful campaigns ensured a tribe’s access to valuable resources, which in turn guaranteed the community’s survival and prosperity. In regions where resources were scarce, the ability to defend or expand territory through warfare was particularly crucial.

Warfare was instrumental in shaping intertribal relations. It was used not only as a means of exerting dominance but also as a way of forming strategic alliances. Marriage alliances, tributes, and the exchange of goods often accompanied peace treaties, weaving a complex network of relationships among tribes. These alliances were essential for maintaining a balance of power and for collective security against common enemies.

In cases where tribes faced external threats, warfare served as a unifying force, bringing together different groups under a common cause. The confederation of tribes, such as the Iroquois League, exemplifies how warfare-related strategies could lead to strong political structures capable of governing large territories and diverse populations.

Warfare also had ceremonial and legal aspects that were integral to tribal governance. War councils played a critical role in decision-making processes, where leaders and elders discussed whether to pursue peace or war. These gatherings were not only strategic but also ceremonial, imbued with rituals that sought to ensure the correctness of the decision in the eyes of the community and the spiritual world.

Moreover, the outcomes of battles often influenced the legal standing of tribes, affecting their rights to land, resources, and respect from other tribes. The enactment of warfare, therefore, was deeply embedded in the legal traditions of Native American societies, serving as a means of enforcing tribal law and sovereignty.

In summary, the social and political functions of indigenous warfare were critical to the structure and survival of Native American tribes. Through warfare, tribes managed their resources, resolved conflicts, built alliances, and structured their political and social hierarchies. This complex role highlights the sophisticated nature of indigenous governance systems, where warfare was seamlessly integrated into broader social and political practices.

- European Misinterpretations and Ethnocentrism

European interpretations of indigenous warfare were deeply colored by ethnocentric biases and misconceptions, which played a significant role in shaping the interactions between Native American tribes and European colonizers. These misinterpretations arose primarily from a fundamental lack of understanding and appreciation for the complex cultural, social, and spiritual dimensions underpinning Native American warfare. As a result, European observers often wrongly characterized indigenous combat tactics and strategies as primitive or underhanded.

The guerrilla tactics employed by many Native American warriors—such as ambushes, surprise attacks, and strategic retreats—were particularly perplexing to European military minds accustomed to the formal battle lines and open combat of contemporary European warfare. Europeans viewed the battlefield through the lens of chivalric and formal military traditions where the valor of a soldier was measured in direct, open confrontation. Hence, they often misjudged Native American war tactics as cowardly or indicative of a lack of martial discipline and bravery.

This critical misunderstanding stemmed from a failure to recognize the tactical intelligence in using the terrain and element of surprise to one’s advantage, which are now considered hallmarks of sophisticated military strategy. The European misreading of these tactics as signs of cowardice rather than strategic acumen underscores the deep cultural chasm that existed between the two groups.

Moreover, European narratives frequently employed the term “savage” to describe Native American warfare practices, particularly focusing on aspects like scalping and the physical brutality of combat. These descriptions often lacked context and failed to acknowledge similar practices within European history, such as the display of heads on spikes or the drawing and quartering of bodies, which were common in Europe for centuries. This selective portrayal served to dehumanize Native Americans, casting them as barbarians outside the bounds of civilized warfare.

The ethnocentric lens distorted European interpretations, simplifying a complex array of indigenous cultural practices into crude stereotypes that justified colonialist policies and expansionist agendas. It provided a moral rationale for the often brutal treatment of Native American peoples under the guise of bringing civilization and Christianity to the purportedly lawless and savage lands.

These misinterpretations had profound implications for diplomatic relations and conflict resolutions. Europeans often entered negotiations with preconceived notions about Native American honesty and intentions, expecting duplicity and preparing for betrayal where none might have been intended. Such attitudes made genuine understanding and respect difficult to achieve, fostering mistrust and hostility on both sides.

Additionally, the failure to appreciate the political and ceremonial importance of warfare in Native American societies led to misunderstandings in treaty negotiations. Europeans frequently misinterpreted what were intended as symbolic or ritualistic acts of war, responding with disproportionate violence that escalated conflicts unnecessarily.

The European inability to recognize the legitimacy and complexity of Native American warfare was part of a broader pattern of cultural arrogance that characterized much of the colonial era. This arrogance not only justified the dispossession and subjugation of Native American peoples but also led to a loss of valuable knowledge and the destruction of sophisticated indigenous socio-political systems that had thrived for centuries.

The European misinterpretation of indigenous warfare practices, driven by deep-seated ethnocentrism and cultural superiority, significantly affected the course of history in the Americas. It contributed to the tragic narrative of conflict and misunderstanding that marred relations between Native Americans and European settlers, the effects of which are still felt today. Understanding these historical misinterpretations is crucial for correcting the record and fostering a more respectful and informed appreciation of Native American heritage and history.

- Pure evil?

“They tore my poor son from my breast […]. They took our little children, impaled them on spits, held them over the fire and roasted them in front of our eyes” – goes one account of the Iroquois, famous for their violence and love of war. There are many more similar accounts of the pioneers who settled the New World between the 17th and 18th centuries:

“They stripped the clothes off the two Frenchmen […] painted their faces in the native fashion. Then the enemy [villagers] prepared to greet them – which meant forcing the captives to walk between two rows of [‘hosts’], each of whom proffered them a blow with a stick […] they were led to the central part of the village, where they were ordered to climb a specially made scaffold. There, one of the Iroquois grabbed a stick and hit René seven or eight times, then ripped out his fingernails.”

The brutal abuse of captives carried out by all the inhabitants of the villages followed the Iroquois’ modus operandi. The misfortunes became the ‘main attraction’ of the elaborate spectacle. Captured enemies had their fingers broken off at once and were taken back to the settlement. Beforehand, messengers would arrive to report the number of those captured. The inhabitants, in order to ‘welcome’ them, would line up in two rows with sticks in their hands. Each prisoner had to pass through such a corridor. During this time, they were mercilessly pounded. Later, their clothes were stripped off and they were led to the centre of the village – to the stage where the ‘performance’ took place.

If the war expedition was in retaliation for the death of the Iroquois, matrons from the families that had suffered the loss would select those captives to be assimilated and (literally) replace those killed. It was believed that the spirits of the dead would ascend to the slaves – in this way the tribe evened out its population.

Those who weren’t so lucky perished in agony. To the sound of drums, the wailing of shamans, dances and burning herbs, their fingernails were ripped off, burned with hotheads, bones and teeth broken, flaps of flesh torn out and parts of the face cut off. The torture could last for hours. The aim was to inflict as much pain on the victim as possible. Before death, the scalp was removed from the victim. The bleeding open skull was sprinkled with ash or sand. When the enemy finally died, the flesh was separated from the bones, cooked and eaten at ritual feasts. In view of such descriptions, is it any wonder that Europeans saw the Native Americans as pure evil?

Women had a greater chance of survival. They were often repeatedly raped, but less often killed. They could become slaves in the indigenous camp or marry one of the warriors. Children were also spared and adopted into the ways of the tribal world. Those slaves who did not die under torture and were not assimilated were allowed to return among their own – as long as someone redeemed them.

“[Comanches] gather in the market and offer captives for sale. If the captive is a woman she is first raped by her owner in front of everyone. Then the warrior says to the buyer: now you can take her, now she is good,” recalled Fray Andres Varo, one of the missionaries in North America.

- Impact of Indigenous Warfare Tactics

The indigenous warfare tactics of Native American tribes, while often misunderstood or negatively portrayed by European colonists, were in fact highly sophisticated and intricately tailored to the specific environmental and social contexts of their communities. These tactics were not just methods of warfare but also instruments of broader social and political engineering, particularly evident in the strategies employed by the Iroquois Confederacy.

The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee, exemplifies the advanced nature of indigenous military strategy. Comprising several tribes including the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and later the Tuscarora, the Confederacy utilized a combination of political diplomacy and military action to become one of the most powerful entities in northeastern North America. Their military prowess was not just about combat effectiveness but also about the strategic use of warfare to secure and expand their territorial and political influence.

One of the key elements of Iroquois warfare was the strategic integration of military campaigns with their sophisticated political structure. The Confederacy’s central council, which included representatives from each member tribe, coordinated their military efforts. This ensured that their warfare tactics were closely aligned with broader political objectives, such as controlling trade routes, acquiring resources, and expanding their influence over other tribes and European settlers.

The Iroquois were also adept at psychological warfare, using fear and reputation to their advantage to prevent actual conflict. Their reputation as fierce warriors often preceded them, allowing them to achieve objectives through intimidation and diplomacy without resorting to actual combat.

The environmental adaptation of the Iroquois warfare tactics is another testament to their sophistication. They made excellent use of the geographical features of their territory, which was characterized by wooded areas, lakes, and rivers. These natural features were used strategically for defense and as conduits for surprise attacks. The waterways, in particular, were used not just for transport but also for launching swift raids into enemy territories.

Socially, warfare was deeply embedded in the Iroquois culture and was a key component of male identity and status. Success in battle contributed to a warrior’s social standing within the tribe, influencing his role in both political and ceremonial life. This social aspect of warfare also motivated warriors to adhere to and develop effective combat strategies that enhanced their honor and standing within the community.

The effectiveness of Iroquois military strategies is evident in their ability to maintain autonomy and influence in the region well into the period of European colonization. Their strategic alliances and treaties with Europeans were often negotiated from positions of strength, derived from their military capabilities and political cohesion. This not only ensured their survival but also allowed them to exert considerable influence over the colonial policies affecting their territories.

The indigenous warfare tactics of the Iroquois Confederacy illustrate the complex and dynamic nature of Native American military strategy. Far from being primitive, these tactics were calculated and sophisticated, integrating seamlessly with their environmental understanding and social structures. The Iroquois’s ability to maintain their power through a combination of military strength, political diplomacy, and strategic alliances underscores the impact and sophistication of their warfare tactics.

- Cultural and Ethical Dimensions of Indigenous Combat

Indigenous warfare was governed by a complex array of cultural and ethical norms that distinguished it sharply from European martial practices. These norms were not just tactical choices but were deeply imbued with spiritual significance and linked to the broader cosmological views of Native societies. This system of warfare ethics was integral to maintaining both cosmic balance and social order, reflecting a holistic approach where warfare was woven into the fabric of spiritual and community life.

Native American tribes often adhered to strict codes of honor that regulated the conduct of warriors during and after battles. These codes were more than strategic or pragmatic considerations; they were moral imperatives that reflected the tribe’s core values and spiritual beliefs. The conduct of each warrior was not only a personal matter but a reflection of the tribe’s collective honor and spiritual health.

For instance, many tribes practiced rituals before engaging in battle that included fasting, prayer, and purification. Such rituals were meant to prepare the warriors spiritually and morally for combat, ensuring that their actions on the battlefield were in alignment with tribal ethics. Warriors were often required to act not out of hatred or anger but as agents of their community’s will, with a clear moral mandate to restore balance or rectify a wrong.

The practice of counting coup, as noted among the Plains tribes, is a prime example of how indigenous ethical norms influenced combat tactics. This practice involved warriors striking or touching their enemies with a hand or a stick and then escaping unharmed. More than just a display of bravery, counting coup was a profound demonstration of skill and restraint. It emphasized courage and cleverness over sheer lethality, valuing the warrior’s ability to outwit and outmaneuver the opponent rather than to kill.

Counting coup was often celebrated more than killing an enemy because it required greater bravery to approach and touch an opponent while avoiding harm. This act conveyed honor not only upon the individual warrior but also upon his tribe, enhancing his status within the community while adhering to a culturally sanctioned form of warfare that prioritized honor over destruction.

These practices stand in stark contrast to the European emphasis on battlefield prowess and conquest, where victory was often measured in terms of casualties inflicted and territory gained. In many Native cultures, the integrity of the approach to warfare, the honor of the warriors, and the adherence to spiritual and ethical laws were as important, if not more so, than the outcome of the battle itself.

European observers frequently misunderstood these practices, interpreting restraint as weakness and the complex social rituals associated with warfare as superstitious rather than recognizing them as part of a coherent ethical framework. This lack of understanding led to significant misinterpretations of Native intentions and strategies, contributing to the tragic conflicts and consequences of colonial encounters.

In many Native societies, warfare was seen as a necessary but regulated aspect of life, intended to restore balance and harmony within the universe. Acts of war were therefore closely linked with cosmic events and spiritual beliefs, and victories in battle were often seen as signs of favor or support from spiritual forces. This cosmological dimension of warfare reinforced the need for ethical conduct, as any deviation from the moral and spiritual laws could invite not only social disapproval but also cosmic retribution.

As we reflect on these profound connections between combat, culture, and spirituality in Native American warfare, one might wonder how different historical outcomes might have been if these indigenous practices had been understood and respected rather than dismissed. Could a deeper appreciation of these rich cultural traditions have altered the course of Native-European relations?

- The dance of the manes

Today, anthropologists of culture and ethnohistorians who look at Indigenous customs are able to ‘decode’ the meaning of violence. However implausible it may seem today, it served the function of strengthening the unity and cohesiveness of the tribe. At the time of the colonisation of the Americas, though, few were able to take a broader view and try to understand the world of the indigenous inhabitants of the continent. The cruelty of the tribes, the violence, raids, torture, rape, the desecration of corpses – all these served as justification for the increasing harassment, swelling violence, genocide, fraud and dispossession of the local people from their native land by the white settlers and the US state.

Those who saw the natives as nothing more than bloodthirsty, cruel savages, those who often had love of humanity on their lips, proved to ultimately become bloodthirsty beasts themselves. On 29 November 1864, 700 of Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado soldiers opened fire upon 200 Cheyenne and Arapahos encamped at Sand Creek Lake, mostly old men, women and children. The intervention turned into a bloodbath. Soldiers pulled scalps from the heads of Indians, tore open the stomachs of pregnant women, cut off the victims’ noses, ears and gouged out their eyes. They also arranged a hunt for the youngest boys. The target in the shooting competition was a three-year-old child.

One cannot comprehend the cruelty of the Indians without taking into account their worldview and beliefs.

Decimated by disease and war, famine and the disintegration of natural tribal structures caused by the culling of buffalo herds, Native Americans confined to reservations looked for hope – some in alcohol, others in the promises of shamans. By the end of the 19th century, those on the Dakota reservations began to promote a belief in a soon-coming “white apocalypse” that would allow the Indians to reclaim their land and dignity. To this end, they indulged in a dark “dance of the manes”, a kind of prayer expected to bring back the buffalo and banish the newcomers from across the ocean.

On 29 December 1890, in the Lakota village on Wounded Knee Creek, the army tried to enforce a ban on these dances. However, the situation got out of hand. The military began shooting at defenceless residents of the reserve. Several hundred Indians were murdered, including many women and children, as well as Chief Bigfoot. The commanding officer of the troops who carried out this slaughter, Colonel James Forsyth, although indicted, escaped responsibility. Public opinion was, indeed, firmly on his side, expressing more or less openly the view that the Indians “deserved” what happened to them.

Some explicitly called for a “final solution” to the Indian question. Among those calling for a ruthless crackdown on the natives was L. Frank Baum, later author of “The Wizard of Oz.” In columns for the press, he expressed the call for: “the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians and the wiping out of the face of the earth of these uncontrollable and untameable creatures”.

Neither did the American state flinch from compensating the Lakotas for their losses, despite the fact that General Nelson Miles sought to do so for the rest of his life. However, he found no heed in the ranks of the army or in Congress. The Sand Creek Massacre closes the period of wars between the white colonisers and the natives. who in short phrase lost the clash of civilisations… Although the “white man” shunned violence and cruelty, ultimately inflicted a cruel fate on millions of indigenous people. by stripping them of their land and their dignity – perishing their entire world.

As we draw today’s discussion to a close, we’re left to ponder the shadows cast by history, shadows that stretch long and deep over the landscapes of the Americas. It’s a narrative steeped in blood, marked by conquests, and punctuated by the all-too-frequent silencing of those who stood in the way of progress—or so it was called.

The indigenous peoples of this vast continent didn’t just wage war; they engaged in a heterogeneous dance of survival, deeply intertwined with the spiritual and the existential. And yet, as Nietzsche might remind us, “Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.” How hauntingly these words resonate when we reflect on the European conquest of the Americas. In their relentless march towards civilization, did the conquerors themselves not become the very monsters they feared in the wilderness? Did they not gaze so long into the abyss of the unknown that they were swallowed by their own dark ambitions?

This saga of conflict and culture reveals more than just the missteps of history. It lays bare the perennial human tragedy: that in our pursuit to dominate and civilize, we often destroy the very essence of humanity—compassion, coexistence, and the rich tapestry of cultures that make up our world. The Native Americans, with their complex societies and profound connections to the earth, were not relics of a primitive past; they were the bearers of different truths, truths that were inconvenient to the narratives of power and progress.

So, as the echoes of the past reverberate through the corridors of time, we must ask ourselves: What have we truly conquered? The lands, the peoples, or just the pages of history books written by the victors? And in this conquest, what have we lost? Perhaps, in our quest to shape the world in our image, we have lost the ability to see the world as it truly is—a mosaic of different images, each valuable, each necessary for the full picture of humanity.

In the cynical moral that befits the spirit of Nietzsche, we might find a dark irony. For in every attempt to civilize another, we uncivilize a part of ourselves. Every act of erasure against another culture is a shadow cast upon our own soul. And in this grand narrative of conquest and civilization, perhaps the greatest casualty has been our ability to understand, to truly see the ‘other’ — not as savages, not as relics, but as mirrors reflecting our own faces, distorted by the lenses of power and prejudice.

Thank you for joining me on this profound journey through “The Dance of the Manes.” May it leave us all a little more thoughtful, a little less certain, and a lot more questioning of the paths we choose to walk in this world.

References:

Deloria, V. (1969). Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. Macmillan.

Edmunds, R. D. (1993). The New Warriors: Native American Leaders Since 1900. University of Nebraska Press.

Jennings, F. (1975). The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest. University of North Carolina Press.

Krech III, S. (1999). The Ecological Indian: Myth and History. W. W. Norton & Company.

Mann, C. C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf.

Richter, D. K. (2001). Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Harvard University Press.

Wojtczak, J. (2007). Quebec 1759: The Battle That Won Canada. McBooks Press.

Marcin moneta “Szlachetny indianin? Nic podobnego! Mit mija się z rzeczywistością” – Ciekawostki historyczne.pl (29.11.2020)

B. Hlebowicz “Okrótniejsi od Tygrysów. Sztuka wojenna, tortury, sny I mity Irokezów”, Laboratorium Kultury 4 (2015)

J. Wojtczak, Apacze. Tygrysy rasy ludzkiej, Wydawnictwo Napoleon V 2019

J. Wojtczak, Indianie I baiłe twarze. Starcie cywilizacji, Bellona 2017

(All citation in my own translation)